Where Did the Anasazi Come From?

When you first see an abandoned Anasazi ruin, you ask, “Where did they all go?” But then you begin to wonder where they came from in the first place. Did outsiders arrive, invaders from another culture, and subdue the locals? Or were the Anasazi homegrown?

It’s a simple question, but I warn you that it is entirely without simple answer.

Where did the Anasazi come from? Could they have been homegrown?

The period from A.D. 700-1130 saw a rapid increase in population due to consistent and regular rainfall patterns. Studies of skeletal remains show that this growth was due to increased fertility rather than decreased mortality. However, this tenfold increase in population over the course of a few generations could not be achieved by increased birthrate alone; likely it also involved migrations of peoples from surrounding areas. Innovations such as pottery, food storage, and agriculture enabled this rapid growth. Over several decades, the Ancestral Puebloan culture spread across the landscape. —Wikipedia

If the birthrate can’t supply the people, then we can’t call it homegrown. That’s pretty straight up.

But it doesn’t explain why people would move into an area and start making babies. Was it just small farmer families taking advantage of a decades-long wet period of easy times growing a bumper crop of corn and beans and greens?

Okay. That’s pretty straight up too. I can imagine that happening.

But why would they spontaneously construct the largest apartment-style buildings in the world? And build long, straight roads to nowhere?

They wouldn’t, without a very powerful reason.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? Not from the loins of mothers born and raised in the Four Corners.

What exactly do we mean when we say “Anasazi” anyway?

There never was an “Anasazi tribe”, nor did anyone ever call themselves by that name. Anasazi is originally a Navajo word that archaeologists applied to people who farmed the Four Corners before 1300 AD. —BLM

Well, that solves all our problems right there! By definition, if they farmed anywhere in the Four Corners region before 1300, they were Anasazi—no matter if they were born there or moved in. Until they started farming, the Anasazi didn’t even exist.

It’s like saying all the land rushers in Oklahoma when it opened for non-native settlement didn’t exist until the first land rush happened. Anasazi is a description of behavior, not cultural origin.

But it’s kind of a chicken way out. Did local non-farmers become farmers (and therefore flash instantaneously into history as Anasazi), or did farmers from elsewhere move in—with their architects and their stonemasons and a few advisors? Oh, and security forces, too, of course. The weak but shrewd always surround themselves with those.

The pre-Anasazi were roving big game hunters.

For 5,000 years, from roughly 10,000 to 5,000 B.C., small bands of Clovis hunters and gatherers and their successors…roamed the Southwest. At the beginning of this period, in Clovis times, a cooler, wetter, late-Ice-Age climate prevailed. Giant game animals—among them mammoth, huge bison, camels, horses, and exotically horned elk—provided meat to supplement the small game and edible plants that these people sought in their ceaseless trek. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 14

Given twenty years per generation (a good guess for ancient cultures), 5,000 years is 250 generations. That’s a long time to do nothing but migrate around hunting big game.

Can you imagine the traditions that would become ingrained in such a long time of very little change?

Those are the traditional roots of the people who became the Anasazi.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? They came from post-Ice Age hunters.

The pre-Anasazi population of New Mexico was very low density.

For the 5,000 years of the Paleo-Indian period [10,000 to 5,000 B.C.], population in what is now New Mexico probably fluctuated between 2,000 and 6,000 persons at any one time—a density of one person per 20 to 60 square miles. At these low population densities, technological and demographic change was agonizingly slow. Approximately one distinct new style of stone point for hunters’ lances and long darts was created every 500 years. It must have seemed a timeless world to those who spent whole lives on trek in small bands. —Stuart/Anasazi America pp. 14-15

I like that: A timeless world.

There must have been elders in the Paleo-Indian world who looked down on something like corn. “I’m not eating that swill, and anybody who does will lose all the power of the spirits of the animals we hunt.”

Or someone notices corn grows bigger and better when you pull off the top tassels and rub them on the corn silk, you get a much better ear of corn: “We’ve never done it that way before, and we’re not going to change now.”

By that comparison, the world of the Anasazi must have seemed like change at breakneck speed.

The pre-Anasazi population of New Mexico exploded after the big game went extinct.

[By 3,000 B.C.,] we can guess that 15,000 to 30,000 souls lived in what is now New Mexico at any one moment, a stunning increase over the 2,000 to 6,000 probably tenants during the Paleo-Indian period [10,000 to 5,000 B.C.]. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 20

This must be because they began to focus more on plant foods, foraging and gardening, which is a more efficient way to use the calories produced by any landscape.

As a family raising children, it would have been far easier to stay put and work the garden than to endlessly pack everything up and travel every few days. That alone could have encouraged larger families, which would grow the population.

Climate change forced the Paleo-Indians to evolve into the Anasazi.

Had climate not begun to change more rapidly and radically after 5,000 B.C., the story might have ended there without ever creating the Anasazi farmers as we now know them. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 16

Environmental change rewards people who make choices to adapt to those changes and penalizes those who do not.

It would take something like external climate change to break the endless cycle of life practiced by the Paleo-Indians for hundreds of generations.

When you nearly starved last year because your corn crop was so pathetic, rubbing corn tassels against corn silk to yield a better ear might seem like a wise and genius thing to do, tradition be damned.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? From hunters who became farmers because game became scarce and farming became much more attractive.

The evolution of the Anasazi from Paleo-Indians was a long and slow process.

The Anasazi culture…grew by continuous transitions and additions and accretions from an ancient and widespread culture [that] came into existence some 11,000 years ago and monopolized most of the territory in the Great Basin—that is, from Oregon and Idaho southward through Nevada, Utah, and parts of California and Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico—and extended into the northern part of Mexico. —Martin p. 19-20

The transition from Paleo-Indian big-game hunter to sedentary Anasazi farmer wasn’t punctuated by a sudden event or epiphany, but happened with what we would interpret as excruciating slowness.

Who were the earliest Anasazi?

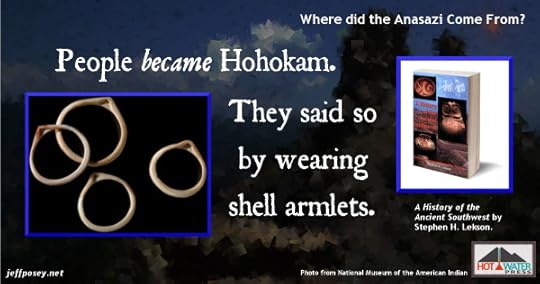

People became Hohokam. Perhaps the most conspicuous and widespread markers of Hohokam were armlets of Glycimeris shell. Bivalve shells from the Gulf of California were carefully shaped into armlets and sometimes carved with symbols—birds carrying snakes, desert toads, and the like. Shell bracelets or armlets became a badge or marker of Hohokam; they had once been rarities, but after 700 they were ubiquitous. Someone in every sizable settlement had armlets prominently displayed on an upper arm. —Lekson

Hohokam are predecessor to—at least highly influential to the development of—the Anasazi. They stayed separate from the Anasazi, but they were probably the mother culture.

To the Anasazi, the people who lived over the mountains to the southwest, the canal-builders and ball-court players (the Hohokam)—they may have been the oddball cousins that upstanding members of the Chacoan Anasazi elite didn’t mix with anymore.

The Anasazi migrated from the north.

Some 700 years ago, as part of a vast migration, a people called the Anasazi, driven by God knows what, wandered from the north to form settlements like these, stamping the land with their own unique style. —NYTimes

From the north? The farmers of the Four Corners who, by rite of farming there, became Anasazi, came from the north?

Corn came from the south. Beans came from the south. Cotton came from the south. But the farmers themselves came from the north.

Did somebody call an ancient job fair convention? Wanted: Farms Down South. A horde of men, wanting to better themselves, migrated there to find growing corn and beans (seeds supplied from the south) make for an easy life, began pumping out children, and then spontaneously started building enormous stone buildings with remarkable architectural similarity.

Maybe the royal architect was from the north. With all his royal attendants, and when they arrived to find all these farming families with children like rabbits, he somehow convinced them to build enormous stone buildings.

It keeps coming back to that. What motivated them to build? What pushed them into a hierarchical society that directed enormous public projects?

Farming would have provided that calories. But something else provided the motivation.

What do Native Americans say about the Anasazi origin?

Modern Pueblo oral traditions hold that the Ancestral Puebloans originated from sipapu, where they emerged from the underworld. For unknown ages, they were led by chiefs and guided by spirits as they completed vast migrations throughout the continent of North America. They settled first in the Ancestral Puebloan areas for a few hundred years before moving to their present locations. —Wikipedia

Many worldwide indigenous cultures developed a mythology about the first people having emerged from under the ground, like being delivered from the womb of our mother the Earth, followed by a journey to find the right place to live.

But that doesn’t really tell us where the first Anasazi people came from.

The pre-Anasazi wandered across North America.

The ubiquitous spiral symbol of Anasazi rock art may be a “written record” of the vast wandering migrations across North America before they settled in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest.

According to Pueblo oral traditions, different groups came from different directions and points of origin before meeting to form the clans and communities of today. Modern Pueblos speak several different languages and do not share a common term for their ancestors. The Hopi name is Hisatsinom. —BLM

It’s difficult to imagine North American before the influence of Europeans. Our first accounts by eyewitnesses come years if not generations after the first wave of microbial sickness spread through the native population, pathogens entirely new to the population of the Americas, carried when Columbus stepped ashore in 1492.

Prior to all European contact, before horses and carts brought the Spanish in the 1500s, might there have been vast migrations of people and cultures, moving to their own rhythm across the plains and foothills like bison?

The original American settlers were pioneers, small migrations of their own. In ancient native America, migrations and wanderings would be part of survival from their deep roots as Paleo-Indians hunting the mega-fauna after the last Ice Age, and become part of the lore of the people.

Migrations were, and still are, literally in their DNA.

The Navajo say an evil magician forced their ancestors to build in Chaco Canyon.

The National Park Service (NPS) signpost at the path’s entrance vaguely describes Kin Klizhin as a place of “ceremonial function.” But [Taft] Blackhorse [a Navajo Nation archaeologist] explains that the kiva served as a human sacrificial altar and a center for ritual cannibalism. His story, like everything else about Chaco according to Navajo belief, is about the Gambler, an evil magician with a hooked, crooked nose who enslaved the ancient Navajo and forced them to build the great houses of Chaco. —Archaeology

This is interesting and all, but the Navajo didn’t arrive in the Four Corners region until about 1400. The Anasazi had mostly abandoned the region by 1295.

So, the Gambler didn’t do it.

Though, for the sheer sake of storytelling alone, there must have been an evil magician with a hooked, crooked nose. On that one, I hereby declare the Navajo exactly right.

And did you notice that reference to ritual cannibalism? That keeps coming up.

The Gambler of the Navajo arrived on a giant lizard.

According to [Taft] Blackhorse [a Navajo Nation archaeologist], the Gambler rode out to Kin Klizhin on a large reptile that was his guardian. His priests sacrificed humans at the site, and the Gambler, says Blackhorse, came here “to swallow their souls.” This is not the tale the NPS tells visitors to Chaco. —Archaeology

I love the imagery. An evil sorcerer riding a dinosaur, sacrificing humans and swallowing their souls. That’s a tale that could rival King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Or The Hobbit and JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy.

But it’s these very kinds of traditional oral stories that make you stop asking what the modern Native Americans believe about the Anasazi and start looking at hard archaeological evidence. Because while oral stories may have grains of truth hidden in them, they’re encased in the fanciful and absurd.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? From a crazy man riding a giant lizard, of course.

The Anasazi were influenced most by neighboring Hohokam, Mogollon, and Mexican cultures.

Most of the later and so-called higher developments of the Anasazi came to them from the Hohokam and Mogollon groups, so that the climax that occurred about A.D. 1100 may be regarded as an accumulations of southern and possibly Mexican traits that were taken over by the Anasazi bit by bit—by trade, by drift, perhaps by war—and reworked to fit their ideas and cultural layout. —Martin p. 20

Trade, drift, and war. That’s an interesting triumvirate of culture change.

The Paleo-Indians had trade in shells, beads, and stone tools. They also had drift beyond our ability to imagine. But while violence and skirmishes undoubtedly took place, they didn’t resort to war until society was structured into high levels of power.

It’s axiomatic that the best way to prevent war is to resist cultural hierarchy and social inequality.

Were the Hohokam as regimented as their Anasazi cousins?

By 900 there were hints of hierarchy [in the Hohokam] not within but between towns, with the largest occupying positions of control at the heads of canal systems—positions of power. —Lekson

There was a lot going on in Central and North America around 900. The first year of construction on Pueblo Bonito was 919. The Toltecs of Mexico collapsed about this time. Cahokia (across the Mississippi from St. Louis) rose rapidly.

What was going on? Why all this sudden change? It’s as if the Native Americans, once a free-roaming people, spontaneously decided to put down roots and create large, complex, hierarchical societies exactly as the large, complex, hierarchical societies of Central America were collapsing.

And it’s interesting to draw the line from agriculture to “positions of power.” When you scale up agriculture from small gardens to huge fields that must be watered and maintained, people begin to specialize, and the specialists who control, say, the head gate to the irrigation system would, indeed, be far more powerful than a lowly bean picker.

So we’ve seen that warfare demands leadership and hierarchy, and now we see that large-scale agriculture demands the same.

Could one have come first? Large-scale agriculture that yields stores of surplus food would be something other people would want to take, by force if necessary. Hence agriculture could have planted the seeds that led to violence, and both would lead to an upper class that controls the masses.

Anasazi and Hohokam violence reached warfare levels by 850.

Intervillage squabbles escalated after 700, occasionally reaching levels approaching warfare by 850. Increasing violence also called for leaders, military or diplomatic. —Lekson p. 233

What might these squabbles-cum-warfare have been about? Probably the usual suspects when it comes to humans fighting humans (well, men fighting men): Food, water, women, territory, jealousy, revenge, religion.

I suspect all of these played a part in the violence that ripped through the area.

And I like Lekson’s suggestion for diplomatic leaders. You can’t fight all the time, or everyone loses. There must have been a system of long-distance runners, emissaries with the power to negotiate peace settlements, perhaps even under a system of diplomatic immunity.

The Hohokam unraveled when the Anasazi peaked.

By 1075, at the latest, Hohokam had begun to unravel [just as] Chaco burst forth to dominate the Plateu from 1020 to 1125. —Lekson p. 234

So if the Hohokam, centered in and around Phoenix and Tucson, were the mother culture to the Anasazi, what would their demise mean to the Anasazi leaders? Would it be a warning that the same could happen to them? Or some kind of proof that the Anasazi way was better?

1075 is an interesting year for the Anasazi world. The first building phase of Chimney Rock happened that year. New foundations that were never completed were laid at Pueblo Bonito. And, of course, the Hohokam began to fall apart.

With the rise of a powerful elite, most people became powerless commoners.

With the rise of would-be kings at Chaco, the people found themselves redefined as commoners. Villages with scores of separate individual homes dotted the landscape. Set on a low hill or prominence above the village stood a Great House [where the Chaco elites lived]. —Lekson p. 235

This sounds like the American antebellum South. The master is in the big house, the slaves are in their row houses.

Or feudal Europe, with the well-fed king and his court behind castle walls and mote, the plebes groveling to provide for themselves.

Without outright slavery, there would have been some system of taxation, of farmers sending a portion of their crops to support the elite.

Taxation works best when paired with both carrots and sticks—a good outcome if you pay up, and a bad outcome if you don’t.

What might that have been in the Anasazi world?

If you pay up, the high priests and would-be kings would direct the right ceremonies to ensure good weather and bumper crops. In a series of good years, this would look pretty good.

If you didn’t pay up, what then? Perhaps something violent.

Kivas evolved as community houses, but the elite of Chaco Canyon co-opted them for private use.

In many cases, Chaco elites were sometimes able to co-opt Great Kivas. The largest Great Kiva of its age was built within the walled plaza of Pueblo Bonito—the first and greatest Great House—about 1050. —Lekson p. 235

Is this evidence of an abuse of power?

Not necessarily. But it could be.

Imagine the stir among the lower priests when the first High Priest demanded a private kiva be built within the walls of his house of worship. For generations, kivas had been open to everyone. But now, the biggest and best was inside a gated community, for the exclusive use of the king, his court, and his bureaucracy.

The Anasazi occupation of the Four Corners.

The ancestral Puebloan homeland was centered in the Four Corners region of the Colorado Plateau—southern Utah, northern Arizona, northwest New Mexico, and a lesser section of Colorado—where their occupation lasted until 1280 or so. —BLM

What do they mean, a lesser section of Colorado? That lesser section includes Chimney Rock National Monument near Pagosa Springs, the most Chacoan of outliers. It was an important place. Not to the origin of the Anasazi, but to the time when Chaco Canyon was in ascendance.

And there’s Mesa Verde National Park in southwest Colorado, the most-visited Anasazi ruins.

So, yeah, I bristle at their use of the word lesser for the Anasazi occupation of southwest Colorado.

Were the Anasazi invading “occupiers” like Nazis?

It’s interesting that the BLM uses the word occupation. The Anasazi occupation of the Four Corners lasted until 1280. The Nazi occupation of France lasted until 1944.

Hmm. That bears some thought.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? Maybe they came from the hyper-violent Toltec culture that was failing south of them in Mexico. Maybe splinter groups of Nazi-like invaders stormed onto the scene and forced all the farmers to start building enormous buildings modeled on Toltec/Mayan architecture.

The Four Corners is a hard place to live.

Temperature extremes in a normal year in the Four Corners are on the order of 100ºF from high to low. In a hard year, make that 120ºF. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 15

So, why would people move there? The world is full of what would seem to be better places to live. Especially the bleak expanse centered on Chaco Canyon.

The Anasazi suffered mightily, there is no doubt. A few of the elites may have been comfortable most of the time, but everyone else tolerated conditions that would likely drive we modern Americans insane.

We don’t really know where the Anasazi came from.

No one knows precisely when the ancient Indian people who would one day be called Anasazi first arrived in the Four Corners. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 13

I appreciate this flat admission from a respected Anasazi archaeologist.

At the end of the day, after we’ve examined all the evidence, we don’t know where the Anasazi came from.

Where Did the Anasazi Come From? Nobody knows.

Conclusion

I feel like we’ve taken a spiral-shaped trip trying to figure out where the Anasazi came from, and we’ve only managed to go in circles.

Do you know where the Anasazi came from?

Me either.

They either came from the north, or from the south (splinters of the collapsing Mexican Toltec culture), or rode into downtown Chaco on a giant lizard.

Yeah. I’m as enlightened as if mud were in my eyes.

This is background research for

The Next Skywatcher: Prequel to The Last Skywatcher Triple Trilogy Series, out in paperback, ebook coming soon!

The Next Skywatcher: Prequel to The Last Skywatcher Triple Trilogy Series, out in paperback, ebook coming soon!

Warning! This story contains graphic violence including cannibalism.

“I really enjoyed it. It was well-written.” —Thomas Windes, thirty-seven-year veteran Anasazi archaeologist with the National Park Service.

Raised by his beloved Sky Chief grandfather and a mysterious albino woman, Tuwa expects to become the next skywatcher.

When a strange star appears in the sky, so bright it shines during the day, the High Priest, backed by ultraviolent warriors from the South, demands blood sacrifice.

Tuwa’s grandfather, a vocal opponent of the foreigners, is murdered in a public ceremony, cooked, and served to the stunned crowd. Next in line are Tuwa’s adopted mother and the girl he loves, Chumana.

Unable to watch, Tuwa flees in a blind panic into dark wilderness where he’s rescued by a long-distance trader who collects orphans to protect him and carry his goods.

Three years later, Tuwa returns with his hardened band of orphans intent upon revenge—only to discover that the stakes are much higher than he had imagined.

Mere revenge may not be enough.

Jeff Posey writes novels inspired by the Anasazi culture of the American Southwest a thousand years ago.

“Cultures that have dramatically collapsed,” he says, “should at least compel us to dream up stories about how such things can happen.”

He does not, under any circumstances, advocate cannibalism.

Jeff’s Books on Hot Water Press

Sources

—Wikipedia. Ancestral Puebloan Origins on Wikipedia.com.

—BLM. “Who were the Ancestral Pueblo People (Anasazi)?” Who Were the Anasazi on BLM.gov.

—Stuart/Anasazi America. Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place, by David E. Stuart

—NYTimes. “Vanished: A Pueblo Mystery,” by George Johnson, April 8, 2008, New York Times on NYTimes.com (Great overall article; good fodder for anything on why they disappeared)

—Archaeology. “Insider: Who were the Anasazi?” by Keith Kloor, Volume 62 Number 6, November/December 2009 issue of Archaeology Magazine, a Publication of the Archaeological Institute of America

—Lekson. A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson

—Martin. Digging Into History, by Paul S. Martin (out of print and hard to come by)

Image Credits

Hohokam shell bracelet photo from the Infinity of Nations Art and History Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian at nmai.si.edu

Hopi woman and baby photo from “In the cavity of a rock” on inthecavityofarock.blogspot.com

Photo of Camuy Cave, Puerto Rico, entrance by manwithashadow on DeviantArt.com.

Photo of Anasazi Spiral from “Field notes from the 40th parallel,” via Daniel Wescott on Pinterest.

Photo of Four Corners via Wikimedia Commons: “4corner” by vicki watkins from USA – Four Corners National Monument. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:4corner.jpg#/media/File:4corner.jpg

Photo of wizard via Wikimedia Commons: “Arthur-Pyle The Enchanter Merlin” by Howard Pyle – http://www.oldbookart.com/2008/08/25/.... Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur-Pyle_The_Enchanter_Merlin.JPG#/media/File:Arthur-Pyle_The_Enchanter_Merlin.JPG

Photo of Gila Monster lizard in public domain via U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Wikipedia article on George E. Goodfellow

Photo of German soldiers marching through the Arc de Triomphe on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris (June 1940), from Wikipedia article on “German military administration in occupied France during World War II”: “Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-751-0067-34, Paris, Parade deutscher Soldaten” by Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-751-0067-34 / Kropf / CC-BY-SA. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

The post Where Did the Anasazi Come From? appeared first on Jeff Posey.