‘To have another think coming’ or ‘another thing coming’?

The other day, the chirruping bird alerted me to an issue that I hadn’t previously given much thought to. Is it to have (got) another think coming or another thing?

A tweet for English learners referred to the idiom as ‘another thing coming’, and pointed people to a Judas Priest song titled You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’, the second verse of which goes like this:

If you think I’ll sit around as the world goes by

You’re thinkin’ like a fool cause it’s a case of do or die

Out there is a fortune waiting to be had

If you think I’ll let you go you’re mad

You’ve got another thing comin’

You’ve got another thing comin’

Conversely, a British English speaker, sought to correct a tweet by a British politician that contained the wording ‘another thing coming’.

Metalheads will already know the song. If you don’t, and you want your ear wax blown out, or wish to indulge in some private moshing or headbanging, you can listen to the original version here:

If you prefer a more mellow approach, here’s the link to veteran smoothie Pat Boone’s version — which kinda proves that heavy metal is non-transferable.

The ‘thing’ spelling is repeated, for example, in:

“If they think I’m going to be a Labrador and roll over they’ve got another thing coming,” he says of the [Conservative] party.

Daily Telegraph (British), 2013.

But the ‘think’ spelling is used here:

In the first instance it sounds good, but if people think those big international companies are here for the benefit of New Zealand, they really have another think coming.

New Zealand Parliamentary debates, 2005.

Since both quotations transcribe what people said, it is impossible to know what form of the phrase the original speakers had in mind.

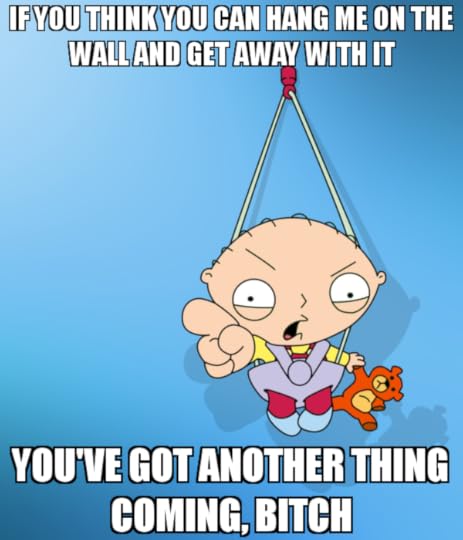

Stewie says ‘another thing’, and he’s a bit of a stickler.

Quick facts

Speakers use both another thing coming and another think coming. and both are part of World English, although only a few varieties of English use either phrase frequently.

Which version you use may depend partly on which variety of English you speak, and which variant you have been most exposed to—and, possibly, on how much of a ‘prescriptivist’ you are.

Whichever version you use, someone somewhere may consider it wrong, but British speakers are probably more likely to consider another thing coming wrong.

The Oxford English Corpus (OEC) and the Global Web-Based English Corpus (GloWbE) both show another thing coming to be more frequent in data for all varieties of English taken as a whole.

In US English, data suggests a marked preference for another thing. In British English, the two forms compete more evenly.

Other data on frequency is slightly contradictory (see further details at end of blog).

All the above suggests to me that, if you’re editing someone else’s work and feel tempted to change this phrase, you might want to have a bit of a think about it.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

Where is the phrase from?

In its original form, according to the OED, it was to have another think coming, and it is American in origin:

Conroy lives in Troy and thinks he is a corning fighter. This gentleman has another think coming.

Syracuse (N.Y.) Standard, 21 May, 1898.

But note that Language Log has a citation from a year earlier, from the Washington Post of April 29, 1897, in the title of an article, and in inverted commas.

It’s worth mentioning that think as a noun is merely a nineteenth-century ‘invention’ (1838), despite the antiquity of the verb (Old English). From discussion in the blogosphere, it seems that some people find it rather odd for think to be used as a noun, which would reinforce their use of thing. (It turns out from figures given below that this noun use of think is indeed rare in US and Canadian English.)

The OED’s first example of another thing coming is from only a few years later, from a book published in New York in 1906:

Now if we should try and think up some one person who is satisfied with the existing order of things.., we would most likely have thought that we should find him in the editor of the Wall Street Journal. But if we did, then we have another thing [1904 Wilshire’s Mag. think] coming.

Wilshire Editorials, G. Wilshire.

(Notice how the OED shows the 1904 rendition of the phrase with ‘think’.)

Is anyone bovvered?

Online searches suggest that, rather than caring deeply about which version is correct, many people are simply puzzled when they come across whichever of the two alternatives is not part of their idiolect.

For example, in my idiolect think is correct, and makes sense meaningwise: it means ‘to think again, to change one’s mind, to have second thoughts’, and that meaning is primed for me by the fact that the phrase often follows a clause introduced by ‘if you/he/she, etc. think(s), e.g., And if you think I ‘m letting you get your hands on my crystals you’ve got another think coming.

Moreover, there are analogous uses of think as a noun—to have a think about something, after a bit of a think, and so on.

However, this noun use of think seems to be rather more common in British and Australian English than in American English, according to the OEC data. GloWbE confirms this: of its 440 examples, 370 are from British/Australian/New Zealand/Irish English, and only 30 from US/Canadian.

Similarly, another thing coming makes perfect sense to the people who use it. In that form, the phrase can be interpreted along the lines of ‘something different from what you expect is going to happen to you’. This makes sense too, since both versions of the phrase are a sort of warning, if not a veiled threat.

And while sentences containing another thing coming also often start with ‘if you/he/she, etc. think(s), that doesn’t appear to deter people from using the thing spelling.

Here is an interpretation from a site on which users raise questions about English usage (englishstackexchange.com):

I also grew up with another thing and I still don’t believe think is original. My thoughts are along the following lines. Ehhmm, Ready?? Lots of people, when laying out the list of arguments for their cause will follow that list with, “… And another thing… ” and go on to list more arguments. This was the origin of the phrase in my mind. Think, I reasoned, was then just someone’s clever pun.

And from comments on a Guardian blog on this topic, it is clear that many people are absolutely adamant about which version is ‘correct’. (There is the usual split in comments between the ‘English is going to the dogs’ and the ‘variation is a fact of language’ brigades.)

Why the alternation?

In simple terms, because the sound at the end of think and the beginning of coming is identical or similar, i.e. /θɪŋk/ and /k-/, it is hardly surprising that word boundaries have been re-analysed as sort of /θɪŋ/ /k-/, which produces another thing coming.

Such re-drawings of word boundaries have historically given English words such as adder, apron, nickname, and umpire.

In practice, the phonetic picture is rather more complex, and it is virtually impossible to tell if a speaker is saying ‘think’ or ‘thing’. (For an exhaustive and illuminating phonetic description of what exactly is going on when someone says the phrase, complete with audio clips, see this Language Log blog.)

What do dictionaries and style guides say?

Neither the Merriam-Webster Concise Dictionary of English Usage nor The Cambridge Guide to English Usage covers it. Burchfield included it in his 1996 edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage, and I have modified it in my edition. The OED describes to have another thing coming as ‘arising from misapprehension’ of “another think coming”’, but the Oxford Dictionary Online (which is not the OED, but a shorter, more modern dictionary) has no note, and does not include to have another thing coming; nor do Merriam-Webster online, the Collins online dictionary, and the Macmillan dictionary.

Facts & figures

Perhaps dictionaries should look at the issue again; no doubt in time they will.

Google

A simple Google for ‘another thing/think coming’ shows them practically neck and neck. However, if you exclude ‘Judas Tree’ from each search, the balance shifts towards ‘another think coming’: (roughly 170 million vs 71 million.) I’m dubious, however, about how useful such a simple search is.

OEC

(February 2014 release; 2.14 billion words)

‘another thing’ = 124

US = 56 (45%)

Brit. = 28 (22%)

unknown = 15 (12.1%)

Can. = 7 (5.6%)

Oz = 6 (4.8%)

Remainder (India, Ireland, etc.) = 12

‘another think’ = 94

Brit. = 35 (37%)

US = 29 (30%)

unknown = 11 (11.7%)

NZ = 9 (9.6%)

Oz = 2 (2.1%)

Can. = 1 (1.1%)

Remainder (South Africa, India, etc.) = 10

As regards British English vs US English, in the OEC both variants are used in both varieties, but for American English the ratio of think:thing is 29:56, while for British English it is 35:28.

GloWbE

(1.9 billion words)

‘another thing’ = 119

US = 33 (27.7%%)

Brit. = 32 (26.9%%)

Irish = 12 (10.1%)

Oz = 8 (6.7%%)

Philippines = 5 (4.2%)

Remainder (15 countries) = 29

‘another think’ = 66

Brit. = 26 (39.4%)

US = 18 (27.3%)

Nigeria = 4 (6.1%)

Philippines = 3 (4.5%)

Irish = 2 (3%)

Oz = 1 (1.5%)

Remainder (14 countries) = 12

Corpus of Contemporary American

(450 million words; 1990–2012

another thing:another think 20:23

Google Ngrams

Data here suggests that the exact string ‘got another think coming’ is still more frequent, but that ‘got another thing coming’ has been increasing since the 1960s, while ‘think’ has been declining since the 1980s. The picture is similar for English data as a whole, and for US and British English data individually.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Spelling, Word origins