No Relation (Part II)

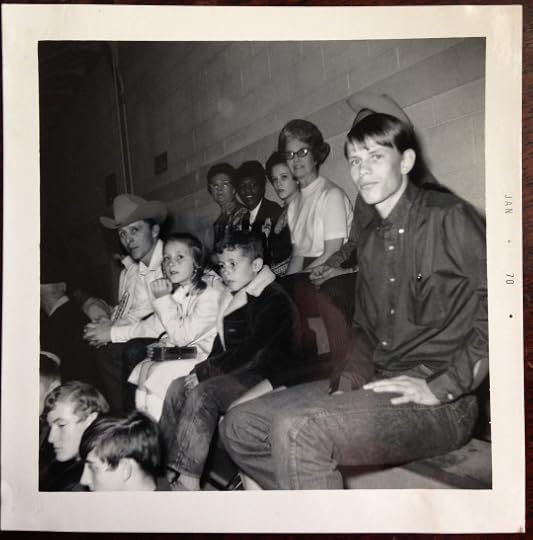

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. Pictured above, my father in the foreground, sitting with his clothing sponsors, 1970. (Not quite a foster family, but the children’s home he grew up in enlisted the help of the community to provide clothing and time away from the home; Lewis and Sandra Light were very dear to him throughout his entire life.)

II.

“There isn’t a hippie in the world that doesn’t want to be a cowboy.” –Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Back to Texas (111)

Creeley’s thoughts on the Western are shot through with romance, so it isn’t a surprise that the editors of this recent volume of letters would follow suit. In the 1982 essay “My New Mexico,” for example, he writes that, “If this is the Wild West of Geronimo and Billy the Kid, it’s also that of White Sands and the first atomic tests—equally brutal and ahuman. Because there is so much outside, such a vast, extraneous skin, such a plethora of virtually useless space, one hands it over to whatever can inhabit it, missile ranges, uranium mines, anything to take it away” (CE 444). (What would New Mexico have looked like if ‘one’ really had handed it over?)

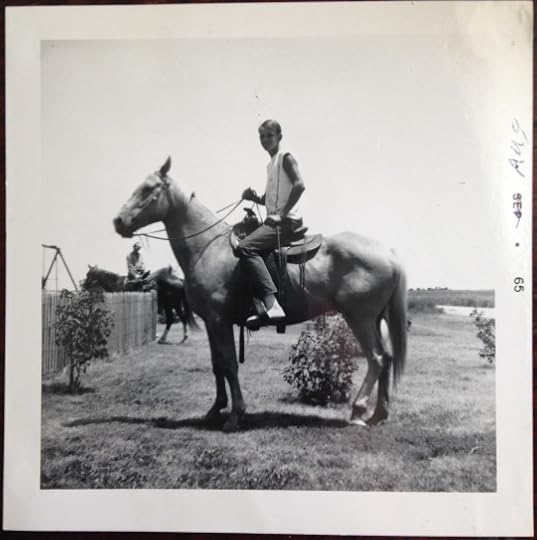

Or, per riding off into the sunset, see the 1983 “Cowboys and Indians” essay, where Creeley tells a story of riding horseback with Bill Eastlake—near Cuba, NM in the summer of 1960—and “threading through the oak brush, meeting with Indians trailing horses, spotting the occasional old-time homesteader who might well have got there before the territory had become the present New Mexico (1912?)” (CE 321-22). (Cuba is located at the southern tip of the Jicarilla Apache Reservation, formed in 1887 and expanded to its current extent in 1907.)

And Creeley’s dependence on the figure of the horse in his own poetics is often really hilarious:

I know that attention to what has been written, what is being written, is a dearly rewarding experience. Nonetheless, it is not the primary fact. Far closer would be having a horse, say, however nebulous or lumpy, and, seeing other people with horses, using their occasion with said horses as some instance of the possibility involved. In short, I would never buy a horse or write a poem simply that others had done so—although I would go swimming on those terms or eat snails. Stuck with the horse, or blessed with it, I have to work out that relation as best I can.

(“Was That a Real Poem or Did You Just Make It Up Yourself?” CE 574)

It strikes me as funny because in one way the horse is part of Creeley’s machismo. He’s not horse people—bird people, sure, at least early on, but mostly he’s poetry people. Cowboy must be some of the most ubiquitous American drag (for ‘real’ cowboys, too). Black Mountain men share with roughnecks (and Kid Rock) this will to offer a heroic western narrative in response to the question, “How’s work?”

My mother tells a story, from when she first met my father, of going to pick him up and him sliding down a guy wire from the top of a rig to greet her at her car on the ground below. At my grandmother’s 80th birthday, my dad and my uncles reminisced about the oil field in the ’70’s, and in their telling, the rig itself did everything but neigh—they rode it high (some literally high), they rode it low. Gunslingers and rattlesnakes made the occasional cameo.

And yet there are real horses and sometimes poets and roughnecks really do meet them. The problem of that encounter is maybe the most apt illustration of how I understand relation, as a dilemma.

My father had a conversation with animals he never had with any human person.

When my brother and I were still kids, dad would sometimes bring home a rattlesnake from the rig in an empty oil drum and keep it in the garage. In his truck he kept a long pole with a wire noose through it in case he came across a snake, but instead of killing them, they became object lessons to impress upon my brother and me the sound they made, how they responded to being confronted by people. He seemed to thoroughly identify with them.

Once, just before I graduated high school, he asked if I’d keep him company on a drive out to a drill site a couple of hours away, in the direction of Marfa. Our talk turned at one point to his reasons for staying in the oil field, and in romantic but economical terms he offered only two: the landscape, the mountain lions.

After the tornado, I’d learn from my mother of the time, midday on some oil field road, when he came upon an enormous hog loose from a nearby farm. The hog stepped right in front of his truck and wouldn’t budge, so dad got out and waited who knows how long, transfixed, until someone came to claim it. According to him, it stood chest-high (he was six feet tall).

Confronting the animal might work as a metaphor for relation in the ‘place’ of address: the audience might as well be mute, for one, but is also somehow indecipherable, requires some kind of nonlinguistic care-as-communication, forcing one to isolate relation itself, to tune out the fuzz and get right down to it, in all its inscrutability.

Creeley published “The Creative” in ’73 (as Sparrow 6), which includes an essay and a poem for his mother, who’d passed in October of the previous year. The essay is mostly really wild, eventually less so—it’s his working-through of the phenomenological problem of creativity. Lots of veering, even through gnosis: at one point he offers the notion of the himma, whereby “the gnostic creates something which exists outside the seat of his faculty,” as a recuperable understanding of what he means by the creative. He cites the following as an instance of this kind of act:

I knew a man once who had a lovely team of horses, this was in West Acton, Mass., and one of them kneeled on a nail was in the planking of the stall, and the knee got infected—Mr. Green* was his name—and Mr. Green, who lived alone with his wife, both about in their seventies, he used to, literally, take the blankets off their bed, this was in winter, and go out into the stall and wrap up that horse and put poultices on her knee, to draw out the poison, and he’d sit there with her, all the night, and finally the old horse, old in its own way as him, got well.

(CE 546-547)

The story illustrates relation, maybe more than himma, as far as I understand it, though I like the idea that care is something that can live externally, something with its own vital force. I like the suggestion that care might be a creative act.

After the tornado, I asked my dad’s older sister to tell me about their life growing up in a children’s home in Lubbock. He never talked about it much, and the only stories he’d told when he was alive had been bleak, about abuse and abandonment, teachers who used 1x2’s on the backs of the heads of mouthy students, ditches dug for no reason and refilled as punishment. My aunt described the time, not long after they’d been left at the home, when my dad, his older brother and two friends plotted to run away. They had responsibilities on the farm attached to the home, though, and it was decided between them that someone would have to stay behind to care for a pig who’d taken sick. They drew straws, and my father stayed. The cops caught everyone else not far from the home, and they were brought back and punished.

That someone was tasked with this care, despite the at-that-point-dire need for escape, and that it precluded escape. The givenness of that relation, in the face of the utter failure of the familial one. It’s Creeley’s phrase, but my father seems from a young age to have had more in common with any animal than with those animals, “the so-called people.”

In Creeley’s talk of ‘the people,’ the distance isn’t easy—much like the distance between himself and Bobbie Louise Hawkins that he traces in “Away.” The people seem to stand at odds with his attempt to locate a place where, in relation to Hawkins, that distance could be bridged, and yet he seeks the people out as part of his vocation. Given the dedication to Hawkins, this poem might read as a love letter, but I love how quickly complicated it gets that there’s an audience—and that she’s in it, somehow, out there, with them—that the poem was published in a book, that he read it at least once for a crowd (at Goddard College, May 18, 1973).** The poem could be rededicated, “For Bobbie & the so-called people.”

He was in Michigan when he completed “Away,” and she in Bolinas—likely freed up to write in his absence, who essentially forbade it.*** The poem comes out of a marriage that was falling apart. The Black Sparrow collection, Away, which contains art by Hawkins throughout, came out right around the time when the couple finally split.

About 30 minutes into the Goddard reading, a disturbance erupts that stages exactly this drama of “I don’t want to talk to the people where the heart is.”**** It’s not a brawl or anything, but a guy in the audience starts heckling—his complaints are almost inaudible, so you really only hear Creeley’s side of the conversation, but it’s enough to derail the reading for awhile. Someone attempts to redirect Creeley by asking that he read the poem about his mother’s death, and he barks back that he’s not going to read that poem.*****

Somewhere in the volatility of this poorly recorded exchange is something that stops me, something I’ve listened to over and over again since. Call it a problem I recognize:

The situation when whatever one makes has become so inextricable from how one understands/processes/engages one’s own experience that writing the experience (of grief, say) becomes not a performance but the real event. So that saying it aloud to some people just literalizes that thing where the artist lives/sleeps/etc. in the installation, for an audience—what I’m trying to name is more like giving the so-called people the keys to the house and letting them watch you cry yourself to sleep, cry yourself awake. Making and experiencing having grown together somehow. The reality of the poem or of writing is thus very close to the reality of the dream—maybe not the real event but, while you’re in it, goddamn real enough.

This essay was derailed for a time by my compulsion to dwell on/in paranoia: my own paranoia in this public display of griefs; the wrenching feeling of reading “LAND” to an audience, recognizable somehow in Creeley’s ’73 reading; my paranoia even before the storm—writing an essay on Helen Adam and the bomb, and writing super irate, super paranoid poems. Derailed by revising my memory of the time just before the storm, in the wake of it—reading back on that time, in my grief, some kind of prescience.

Julia points to the problem’s relation to hysteria, its operating in excess of some inside/outside line—so: the paranoid social = no boundaries. “I’m telling you a story to let myself think about it.” (I.e. because I can’t think it any other way than by telling you, and fuck you for that.) I wish I could say the feeling has since abated.

Vocal or not, grief has an audience at every turn: during the first funeral reception, representatives from Billy Graham’s organization interrupted the meal to donate two copies of The Billy Graham Study Bible to our families, even though (they made a point to note) my dad wasn’t devout like my grandmother. During the funeral procession—which was observed by seemingly everyone in Granbury, who parked their cars and stood beside them—my aunt posted streaming FaceBook updates from the motorcade itself and the service after, so that my mother could watch from her hospital bed. During the clean up after the storm, we met scores of volunteers and lookie-lou’s, and every once in awhile someone would directly request the blow-by-blow. Even months after the event, while I was (reluctantly) touring a firearms manufacturer in Granbury, my brother and I were prompted by our guide to rehearse the details for a bevy of white dudes (some swastika’ed, some simply bearded) who worked the production line.

In such a public performance, we trained ourselves not to disappoint, I think, or else we just crawled in somewhere, and I can’t speak for my brother or my mother, but my sense was that most every time I found myself in the situation of being expected to report that trauma to some stranger, my distance from ‘them’ grew. And I read that expectation into almost every encounter, which can’t have been the case.

Not long after the tornado, we noticed that someone had taken some tools from the house. (No one could stay there, so it was basically left unattended at night.) I called a local mover and asked for some emergency help, and the next day they sent a few volunteer crews to pack the house and move it to a storage unit.

At some point during the move, I was helping my uncle sort through some of what remained of my grandparents’ belongings, and I came upon something that moved me immediately to tears. When he attempted to hug me, I noticed some of the movers could see us and I pushed him away. Can’t change that response.

Towards the end of the day, I found myself in the kitchen talking to a couple of the movers, who were expressing shock at just how much damage the storm had done, and before I knew it I’d launched into the entire narrative. Eventually I realized the audience had grown and there were 15 or 20 men standing there listening, and I could feel myself walk out on my own story to observe the staging of it, a little repulsed and afraid I’d auctioned off my own grief.

For me, Away begs the question of what attention is to begin with. Why do we attend? What compels us? And here, I mean to consider the writing/art itself as an attention (to the world), in addition to the book having an audience listening in.

I won’t claim to be able to read Away without getting somehow wrapped up in what I know of the lives going on behind it, without somehow ‘enjoying’ that drama (is there any other way to say it?). Which makes me sure that the fear about ‘the people’ must have been so much more palpable in situ. I think of Creeley’s paranoia as the result of being a writer of the domestic on the eve of the domestic’s implosion, both personally and culturally.

I don’t want to talk to the people where the heart is…

But isn’t that what we do precisely there? Aren’t the so-called people always part of how we construct relation, even at home? Don’t we relate out of what we know from the various attentions we’ve paid? I just can’t shake the sense that Creeley’s personal turmoil during this time was somehow wrapped up in his finding certain of the people’s demands (i.e. second-wave feminism) so untenable, his refusal to ‘talk to the people’ at home. Like saying, I want discourse checked at the door…

According to Bobbie Louise Hawkins, “When Bob and I were first together, he had three things he would say. One of them was, ‘I’ll never live in a house with a woman who writes.’ One of them was, ‘Everybody’s wife wants to be a writer.’ And one of them was, ‘If you had been going to be a writer, you would have been one by now.’” (Fifteen Poems, belladonna* 2012, p. 32).

Elsewhere, Creeley in an interview on being raised by women:

“Also, growing up with five women in the house, man, I knew all the signs and gestures and contents, or at least I knew a lot of them that were manifest in women’s conduct. Ways of saying things, ways of reacting, making the world daily. But I didn’t have a clue as to what men did, except literally I was a man. It’s like growing up in the forest attended by wolves or something. It took me a curiously long time to come into man’s estate.” (MacAdams interview from ’73, p. 81).

From MacAdams’ introduction to that interview:

“After breakfast Creeley and I went upstairs to his study, a big sunny room looking out across a long wooded valley to Lake Erie. The study had once been a nursery and the framed photographs of Charles Olson and John Wieners, and Bobbie were set off by a pink wallpaper covered with tiny horses and maids.” (72)

Should I tell you the dream about Puerto Rico and the pink Cadillac? Email to Jean Donnelly (1-31-14) on some difficulties of returning to first teachers:

“I hear you re the return: I’ve been really into the ’50’s lately in poetry and letters (set off by nostalgia for some of those first loves and by apocalyptic thinking?), but it’s such a twisted time. It makes sense to me right now to write about Creeley and my dad together because I have roughly the same feeling for RC—like I feel like I learned so much from him but he very often embarrasses me with his having been so slow to get in touch with more than that circle of maleness. I dreamt about my dad last night and we’d traveled to Puerto Rico or something. At some point we spoke to some barkeep and my dad made this face to me about how effeminate the guy was—then I turned around and dad was lifting the body of a pink Cadillac! When I woke I laughed my ass off, cause it seems like gender’s always that kind of awkward demonstration. To read Creeley’s early letters to Olson it gets so thick—what we’ll MAKE Corman do with Origin etc. Seems so far from where I entered his work—can’t say I’d have kept going if I’d begun there.”

…But I think maybe I can’t not have begun there. It may not be such an uncommon shock, that realization of historical blindness on the part of someone whose thinking one otherwise trusts, but what really smarts (for me) isn’t the sense that this lack of foresight, this lack of insight, is somewhere hard-wired into my own thinking given I put myself to school there, but further, that I fucking chose it. The fact of having had to make a concerted effort to unlearn misogyny only followed the condition of having chosen, however casually or naively, to love it in the first place.

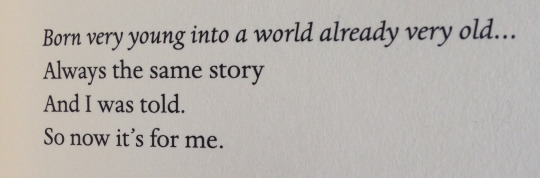

Creeley, “‘Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang…’” (If I Were Writing This, 31).

It’s from a poem written much later in life. When he reads it aloud, there’s the (to me) heartbreaking emphasis: and I was told…

Even in hindsight, no getting off that hook.

Notes:

* John Wieners, in a 1973 interview with Charley Shively, says that Creeley visited him in 1966 and introduced himself to the woman Wieners lived with at the time as “Robert Greene.” (John Wieners, Selected Poems: 1958-1984, Black Sparrow Press, 1998; p. 297.)

** Per the Goddard audio, the poem was completed in Grand Valley, MI on 7/11/71. Creeley notes in that reading that this is “an old Ted Berrigan poem.” At the time of the reading (’73) the poem retained the phrase, “going home,” as its final wording, which phrase is dropped from the published version by ’76.

*** See Fifteen Poems interview. She would have been working on the poems in that book, as well as the brilliant prose of Back to Texas.

**** Email from Bob Grenier, 3-20-14: “I must have been there, probably wd have brought Creeley over to Goddard from Franconia (where I was teaching at the time, where RC wd have just read & stayed), but I don’t remember anything abt it (there was a sort of little ‘North Country Circuit’, back & forth, for people who came to read at both colleges) … I didn’t pick up that there was anything special abt person in audience (I don’t know who that was) who was causing a disturbance—I didn’t sense that there was any 'argument’, just RC trying to shut the guy up so he cd go on w/ the labor of going through w/ reading he didn’t seem to be much interested in (probably not uncommon circumstance, since from that point forward, for another 30 years, RC doggedly went wherever he was asked to go to present his work … that in itself, to me, seems like a kind of 'hell’ … to arrive & 'be oneself’/be the poet everybody so much wants to hear read his poems (for the umteenth time) … I sure wldn’t want to do it !”

***** Sparrow 6, published in March of 1973, included the text of “The Creative,” a lecture delivered 10-21-72 at Johns Hopkins (a week after his mother’s death) and this poem.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers