Bradbury Festival, Part 3: Two Versions of Fahrenheit 451

���Gordon (Sterling Hayden), a bookman, is getting burned out, so to speak, on his job.�� He���s losing the plot on why books are so bad.�� He meets a pretty blonde who sorts confiscated books on a conveyor belt to oblivion.�� The blonde, Susan (Diana Lynn, PLAYHOUSE 90���s go-to ingenue), snatches a book off the belt once in a while.�� Gordon and Susan mark each other as kindred spirits.�� She introduces him to an underground of kindly bibliophiles.�� They fall in love.�� They���re in constant danger of getting toasted by Gordon���s colleagues.�� They look for a way out, a permanent one.

���The story takes some twists and turns, but let���s just say things don���t end well.�� For Gordon or for the rest of the bookless world.�� I won���t exactly spoil the big reveal (not that you���ll ever get to see this thing anyway), but it turns out that the oppressors and the resistance are the same thing.�� ���A Sound of Different Drummers��� was prescient, which is only one reason why it���s so good.���

Sound familiar, yet somehow different?�� The above is a quote from Stephen Bowie���s THE CLASSIC TV HISTORY BLOG reviewing, not Francois Trauffaut���s 1966 film version of FAHRENHEIT 451, but a John Frankenheimer directed drama on October 3 1957 on CBS���s PLAYHOUSE 90, with author credit to Robert Alan Aurthur.�� Bradbury was tipped off while the live broadcast was still on the air, and with that, the sparks flew.

To quote Bowie again, ���Gene Beley���s RAY BRADBURY UNCENSORED:�� THE UNAUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY! (iUniverse, 2006) covers the details of the ensuing litigation, which dragged on for years.�� The upshot: Bradbury lost in court but won on appeal.�� CBS coughed up the proverbial ���undisclosed sum.����� Bradbury���s attorney, Gerson Marks, found a paper trail proving that CBS had almost bought the TV rights to the book in 1952, and that Robert Alan Aurthur had considered buying it when he was story-editing PHILCO at NBC during its final (1954-1955) season.�� Aurthur testified.�� He fessed up to having seen an old summary prepared by Bernard Wolfe, the CBS story editor who optioned FAHRENHEIT 451 in 1952.�� But he denied having read the book itself.���

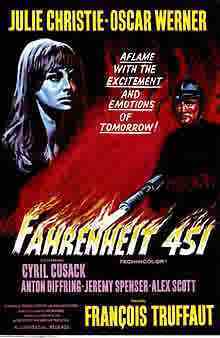

Recalling that Bradbury wasn���t nearly as well known in 1957 — at least outside of science fiction circles — as he is today, Aurthur���s denial is not implausible.�� But as for Bowie���s ���not that you���ll ever get to see this thing anyway,��� well, some of us did this Friday as the opening of an IU Cinema Bradbury Film Festival double feature, Frankenheimer���s ���A Sound of Different Drummers��� at 6:30 p.m., followed by Truffaut���s Bradbury-authorized FAHRENHEIT 451 at 9:30.�� Both are excellent, each in its own way.

For FAHRENHEIT 451 I recall, from my own review of it in 1966 for an “underground” student newspaper, a pervading preoccupation with beauty.�� Colors, motion, swirls of flame, repeated images, reflections of light in actress Julie Christie���s hair — and that there���s a perverse sort of reason for this.�� There are differences, of course, in either version from Bradbury���s original novel, one in Truffaut���s that now the printed word is entirely banned, while the book���s Fire Captain Beatty allowed that ���the public, knowing what it wanted, spinning happily, let the comic books survive.�� And the three-dimensional sex magazines, of course,��� later adding ���you are allowed to read comics, the good old confessions, or trade journals��� (FAHRENHEIT 451, 60th ANNIVERSARY EDITION, New York, 2013, p. 55).�� Or (p. 94) ������What���ve you got there; isn���t that a book?���� I thought that all special training these days was done by film.����� Mrs.  Phelps blinked.�� ���You reading up on fireman theory?�������� But still most entertainment comes from a kind of surrounding TV, on three walls in protagonist Montag���s home, though his wife is nagging him to add a fourth — something a movie can���t reproduce for us, at least not yet.�� So we have to make do with a single wall-screen.

Phelps blinked.�� ���You reading up on fireman theory?�������� But still most entertainment comes from a kind of surrounding TV, on three walls in protagonist Montag���s home, though his wife is nagging him to add a fourth — something a movie can���t reproduce for us, at least not yet.�� So we have to make do with a single wall-screen.

But then this is the joke that Truffaut plays on us, with devastating effect.�� There are no shown titles, instead they are read aloud; only until the very finish with its sign of hope, in the final image, can we actually read the words “The End.”�� Otherwise the only words we see in the movie are snippets of titles on burning books — for in this world reading is dead already and here is the joke Truffaut has played:�� that watching this movie we ourselves, however unwittingly, have become part of Bradbury���s future.

But harking back, there are different ways one can present a future, and here both may be good.�� Black and white TV, of course, on a rather smaller ���wall-screen��� than today adds more limitations.*�� Nevertheless, once again quoting Stephen Bowie:�� ���The director of ���A Sound of Different Drummers��� was John Frankenheimer.�� It was a perfect match.�� The future-world setting and the constant atmosphere of dread and paranoia meant that Frankenheimer could go full-bore with his camera and editing tricks without ever overwhelming the material.�� Constant camera movement advances the story at a freight-train pace.�� None of the sets have back walls; the people of the future live in murky blackness.�� The futuristic props (super-fast cars, robotic psychoanalysts) are cleverly designed and there are special effects I still can���t figure out.�� The most impressive of those is a videophone screen that appears to project the giant, disembodied head of the speaker against a dark wall.���

Two versions, one future.�� And now we���ve been warned, despite the visual flair of the one or the keyed-up drama of the other, to resist its happening.

.

*Not to mention that “Different Drummers” being aired live adds its own kind of problems�� The one we saw was a kinescope, filmed from the TV screen as it was broadcast, complete with commercials and even a preview of the next week’s program.