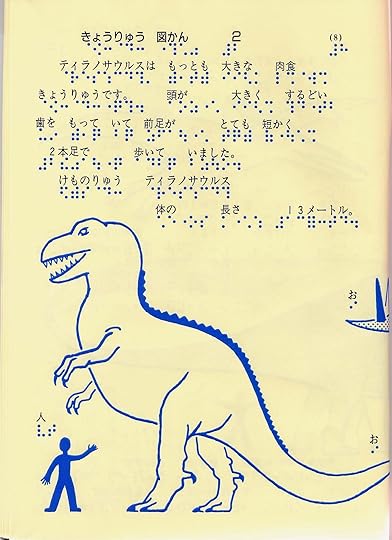

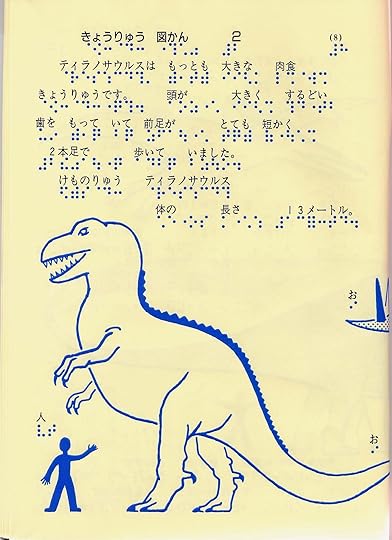

Japanese Braille text from Tips for Language Learning tumblr

I noticed something interesting about the Japanese and spaces. Normally, written Japanese has no spaces.

Consider the first sentence in the page above: ティラノサウルスは 最も 大きな 肉食 恐竜です. Preserving the spaces between the words, that is, “Tairanosaurusuwa mottomo ookina nikushoku kyouryuudes.” Translated word-for-word, that’s “Tyrannosaurus-subject-particle most large-adjective carnivore dinosaur-is” or “Tyrannosaurus is the largest carnivorous dinosaur.”

However, the sentence wouldn’t appear like that in a text for sighted adults. It would appear without spaces, like this ティラノサウルスは 最も大きな肉食恐竜です. That’s impossible in Braille, because 恐竜 (“dinosaur” in kanji) and きょうりゅう (“dinosaur” in hiragana) are written the same, and without kanji to break up the flow of phonetic symbols into words, you get the incomprehensible: Tairanosaurusuwamottomoookinanikushokukyouryuudesu.

The funny thing is that if you want to transliterate Japanese into Roman letters, you have to do the same thing. But English speakers do not chop up the sentence the same way. Rather than stick the particles and other grammatical elements onto the ends of the words they modify, as the author of the book above did, English-speakers tend to let them stand on their own, as if they were prepositions: “Tairanosaurusu wa mottomo ooki na nikushoku kyouryuu des.”

On the one hand, it makes no difference. Whether you write “Tairanosaurusu wa” or “Tairanosaurusuwa,” both are pronounced the same, both mean the same thing, and nobody writes it that way in Japan, anyway.

But in terms of language-acquisition, such distinctions might mean the difference between spending all month trying to wrap your brain around weird Japanese grammar and understanding it intuitively in the first lesson.

Let’s say you’re in a Japanese class and your teacher writes on the board: “お会いできるのを楽しみにしています” (I’m looking forward to being able to meet you)

Then your teacher has to transliterate that sentence for the benefit of the students. English-speaking will probably prefer to see this: “oaidekiru no wo tanoshimi ni shiteimasu.” (honorific-be-able-to-meet genitive-particle accusative-particle pleasure locative-particle doing). The student can think “aha, the particle ni is like “in” in English, it just comes after the noun instead of before. It even looks like a backward “in”!

A Turkish or Russian speaker, however, might prefer the method used by Japanese native speakers (when forced to use Roman letters at all) “oaidekirunowo tanoshimini shiteimasu.” (being-able-to-meet-genitive-accusative pleasure-locative doing). Those students can say, “aha! Noun-declension!”

So what’s the difference between the “cases” of Turkish and the “particles” of Japanese? There are some. But I’m willing to be that the honest-to-goodness cases of Turkish and Russian evolved in the same way, from particles that got mashed on to the words that preceded them. Since Japanese native speakers tend to mash their particles in the same way, perhaps it’s only a matter of time until Japanese, like Latin, declines its nouns.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

so, this is fascinating, and I'm not being sarcastic. But honestly, all I'm interested in is whether spacing issues make for better puns in Japanese or grammar jokes - e.g. pandas eat shoots and leaves.

so, this is fascinating, and I'm not being sarcastic. But honestly, all I'm interested in is whether spacing issues make for better puns in Japanese or grammar jokes - e.g. pandas eat shoots and leaves.