Pancake Day: a pancake recipe linguistic

Butter…eggs…milk…flour…water…sugar…lemon. Those are the basic ingredients of and garnish for a pancake (thanks Delia!).

Simple, everyday words, but ones with complex histories that illustrate why English is such a succulent concoction of so many other languages.

If we look at where those words ultimately come from–simplifying considerably–what do we discover?

��� butter (Greek)

��� eggs (Old Norse)

��� milk, water (Germanic, Indo-European)

��� sugar, lemon (Arabic)

And if you also use syrup, that’s another word from Arabic.

Each has a curious story to tell.

(Flour��has too, but it���s a different tale: it���s a specialized spelling of flower.)

Let���s look at a couple of these words in more detail.

Fine words butter no parsnips

…but butter is essential to make the pancake batter (from French, btw).

How on earth did “butter” come all the way from Ancient Greece?

Like this. The Ancient Greeks seem not to have used butter for cooking, but they knew of its existence. The fifth-century (BCE) historian Herodotus wrote the earliest account, describing how ���the Scythians��poured the milk of mares into wooden vessels, caused it to be violently stirred or shaken  by their blind slaves, and thus separated the part that arose to the surface, which they considered more valuable and more delicious than that which was collected below it���.

by their blind slaves, and thus separated the part that arose to the surface, which they considered more valuable and more delicious than that which was collected below it���.

Hippocrates, the ���father of medicine���, he of the Hippocratic oath, also mentioned butter several times, and prescribed it externally as a medicine. He too described the Scythians making it, and wrote that they called it ���������������� (bouturon).

Folk etymology or loanword?

The 1888 OED entry states that this ���Greek [word] is usually supposed to be ��������� [bous] ox or cow + ���������� [turos] cheese, but is perhaps of Scythian or other barbarous origin.��� In other words, the derivation from Greek might be a folk etymology, and the Greek word might in fact be a loanword.

If you enjoy this blog, and find it useful, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

What the Romans did with butter

Alma-Tadema’s soft porn masquerading as classicism. Exquisitely painted, though!

Greek ���������������� was borrowed by the Romans as butyrum. They, like the Greeks, did not use it in cooking either, but as an ointment in baths (yuck!) or for medicinal purposes, such as mixing it with honey to rub on mouth ulcers or to ease the pain suffered by teething infants.

Finally, the word reaches Britain

Old English had borrowed it at least by the year 1000 CE, when it appears in Anglo-Saxon medicine in the form butere as a remedy for swellings or boils, mixed (if I���ve translated correctly) with pounded yarrow.

English is technically a ���West Germanic��� language, and its cousins German, Frisian and Dutch all also borrowed the word for “butter” from Latin, which is why the modern German is butter, and the Dutch boter.

Beware of Vikings bearing eggs

Another of the ingredients of current English is Old Norse words brought over by the Vikings during their incursions (I choose my word carefully) ��into the British Isles and Ireland from the late eighth century onwards.

Many of them are basic to our vocabulary: words to do with the body, such as ankle, calf, freckle, scab and skin; or basic verbs such as get, give, take and want. These words often replaced earlier Old English words, and **egg is a Norse interloper��(the -loper part of which is from Dutch).

The older word was **ey, (plural eyren) derived from Old English ��g. It seems that the two different words were used concurrently, but by people from different parts of Britain.

One of the best-known illustrations (or “iconic moments“, if you want to be kitschy) of the history of English concerns these lexical twins.

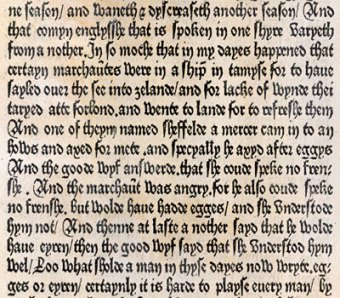

In his prologue to his translation of The boke yf Eneydos… translated oute of latyne in to frenshe, and oute of frenshe reduced in to Englysshe by me Wyllm Caxton (i.e. a paraphrase of what we know as Virgil���s Aeneid), Caxton wrote:

Loo, what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte, egges or eyren? Certaynly it is harde to playse every man by cause of dyversite & chaunge of langage.

(What should a man in these days now write, egges or eyren? Certainly it is hard to please every man because of the diversity of and change in language.)

Caxton was echoing the uncertainty about how to write words at a time when English spelling was becoming a very pressing issue because of the spread of printed books. Dialects within Britain varied far more than they do today, and for Caxton it was important to choose words and spellings that would be understood by as many people as possible.

His remark follows a piquant story

Some merchants–presumably from the north of England, since one is called Sheffield–being becalmed on the Thames and unable to set sail for Holland, want to have something to eat and try to buy eggs from a woman dahn sahf (down south).

The merchants use the Norse and northern English version egges; she uses the southern version eyren. She either was unable to understand, or, like a typical southerner today, decided to wind up the northerner by pretending not to. She added insult to injury by taking him for that worst of all things…a Frenchman!

And that comyn Englysshe that is spoken in one shyre varyeth from a nother…And specyally he axyed after eggys. And the good wyf answerde that she coude speke no frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry for he also coude speke no frenshe but wold haue hadde egges and she understode hym not. And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde haue eyren. Then the good wyf sayd that she understood hym wel.

(Modern English version at the end of the blog.)

What about pancake?

Simples! It���s a straightforward, Middle English combination of pan (related to German Pfanne, and perhaps also ultimately from Latin) + cake (again, like egg, from Scandinavia).

**The Old Norse is echoed in the modern Scandinavian languages: Icelandic & Norwegian egg, Swedish ��gg, Danish ��g; the Middle English ey(e) in modern German and Dutch ei.

In present day English:

“And that common English that is spoken on one shire differs from another…And he asked specifically for eggs, and the good woman said that she spoke no French, and the merchant got angry for he could not speak French either, but he wanted eggs and she could not understand him. And then at last another person said that he wanted “eyren”. Then the good woman said that she understood him well.”

Filed under: Dictionaries & Lexicography, Meaning of words, OED, Word Histories Tagged: Around the world in 80 words