The digital Works of Samuel Johnson

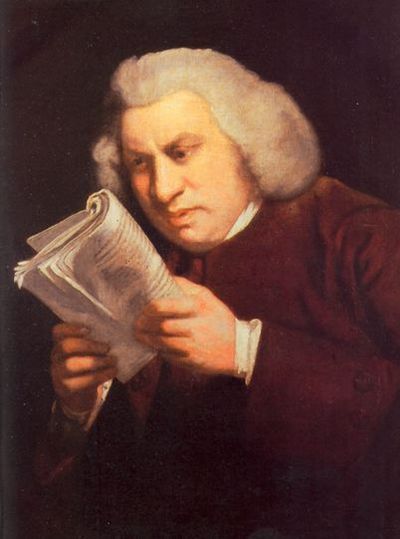

Dr Johnson by Joshua Reynolds (1775)

By CATHARINE MORRIS

In describing the publishing history of the Works of Samuel Johnson at the Dr’s house recently (the history is fascinatingly chequered – more on that at a later date, perhaps), Professor Robert DeMaria, Jr, of Vassar College, the third general editor of the Yale edition, shared a few thoughts about the Yale digital version (free and open to the public), which he and his colleagues launched this year.

It is entirely reliant on the (twenty-one volume) print edition, he said, but it has in a way its own ethos or character. He talked a bit about the process of putting it together. Once a digital text had been created – there was a sharp intake of breath when we were told that the printed pages were not scanned in but typed up by two typists – DeMaria divided it, with the help of his students, into 1,728 “separable and in some way integral pieces” (each of the prayers in Volume One, for example, is a separate piece). And that’s not trivial, he said; any piece can be placed on the screen next to any other.

DeMaria and his students then created the metadata – a spreadsheet with the 1,728 items down the left-hand side and fields such as date of publication, date of composition, genre, publisher and place of publication along the top – which was fed into a digital platform originally designed for the Stalin papers (“These little hammers and sickles would show up . . . . We had to get rid of all of those”). Thanks to the metadata you can now see Johnson’s works arranged chronologically; or you can sort them by genre or publisher. DeMaria suggested that this feature implied "some kind of withdrawal of editorial guidance in favour of readers’ discretion in arranging the materials . . . . Also the barriers between the volumes are broken down. There’s no longer really any such thing as a volume. You can . . . look at the volumes independently if you wish, but you needn’t, and I suspect most people won’t – they’ll search for particular items”.

Another difference, said DeMaria, is that the textual notes are mixed in with the explanatory ones, and they are for the most part out of sight: you click on the relevant letter or number and you’re whisked to a separate area at the end of the section. (Incidentally, you can also add tags or notes yourself, and start discussions with other readers.) Is there a cognitive difference, DeMaria wondered, between “the circumstance in which the eye moves up and down the page” and in which the eye is, effectively, directed to a new page? He thinks that there might be.

It’s possible, using the search devices, to find all the places where Johnson uses a particular word, which is “sort of possible with indexes in printed books, but only very good ones”. There is also a list of keywords, which enables readers to order Johnson’s work by theme or topic.

And this, he said, is something that requires some meditation too: “I think our minds might do that kind of organization anyway when we read a lot . . . . The tool of searching empowers the reader . . . but it also deprives him or her . . . because it reduces the amount of time we spend reading before deciding on classifications. In that time, I think, something creative may be going on that the availability of predetermined classification shuts down. That period of reading when we’re just seeing textual moment after moment without putting it together is the period when we are most likely to develop our own original views and perhaps develop the deepest impressions of a writer”.

This is one aspect of digitization that I hadn’t considered before, and I’d be interested to hear others’ thoughts on it . . . .

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers