Nicolas de Staël and René Char – an intense friendship

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

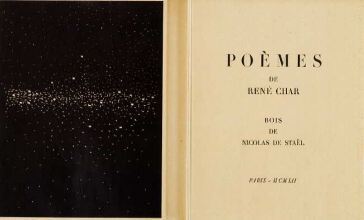

Collaborations between painters and poets are invariably attractive. The brief one between the painter Nicolas de Staël (1914–55) and the poet René Char (1907–88) promised much, but was abruptly terminated by Staël’s suicide at the age of forty-one.

To mark Staël’s centenary, the Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux in Le Havre recently staged an exhibition entitled Nicolas de Staël: Northern Lights – Southern Lights (there was apparently a corresponding show in Antibes, focusing on Staël’s nudes). Le Havre’s light, nicely weathered seafront gallery (which also contains one of the best collections of Impressionist paintings in France) displayed 130 works (80 paintings and 50 drawings), many of them in private hands. These were mainly land- and seascapes – drawings and oil paintings in Staël’s inimitable, transformative style, from the northern French coast to Syracuse in Sicily. In the words of the organizers, “the extraordinary freedom and poetic quality of his work, which straddles the boundary between figurative and abstract art [this was how the artist himself viewed his work], lend it a unique authority”.

"Marine à Dieppe (Plage)", 1952

According to Staël’s daughter Anne de Staël, who has written a preface to a volume of correspondence between Char and her father, published to coincide with the exhibition (141pp. Editions des Busclats. €15), the two produced one book together but planned several further projects. They met in Paris in 1951 and soon became firm friends. Invariably addressing each other as “Mon cher Nicolas” and “Très cher René”, the two men kept up a lively, mutually supportive exchange, occasionally touched by a frenzy of creative excitement on Staël’s part. They were writing to each other from various addresses in Paris and the South of France – Char was from the Vaucluse in the South and very rooted in his region (maintaining his Provençal accent), although he spent time in Paris; Staël meanwhile, constantly in need of money and changing addresses with his young family, moved south late on in his life, first to the medieval village of Ménerbes where he installed his family, and then alone to Antibes in 1954. It was here that he threw himself off his studio terrace.

In between reports from the restless Staël’s travels (Igor Stravinsky is the “most tortuous person he has met” and “a brilliant little gnome”), there is much discussion of the planned book – hermetic poems by Char, beautiful woodcuts by Staël, all amply displayed in the exhibition. At one point Staël refers to “that painter, whose name escapes me, who had himself strapped to the foremast during a storm . . .”; that painter of course being J. M. W. Turner.

Laurent Greilsamer’s biography of Staël (1998, untranslated) is probably the main source for the painter’s life (he has also published a Life of Char, 2005), although it’s not free of that occasional tendency for imagined, reconstructed dialogue. (Why do biographers think this is a good idea?)

According to Greilsamer, Staël’s aristocratic Russian family fled the country in 1919 (his father had been vice-governor of the Peter and Paul fortress in St Petersburg). Both parents died when he was still young and he and his two sisters were taken in by a foster family near Brussels, from where Staël made his way, in his twenties to Paris. An admirer of French culture (who briefly served in the Foreign Legion in North Africa in 1940), he nevertheless didn’t take up French citizenship for a long time.

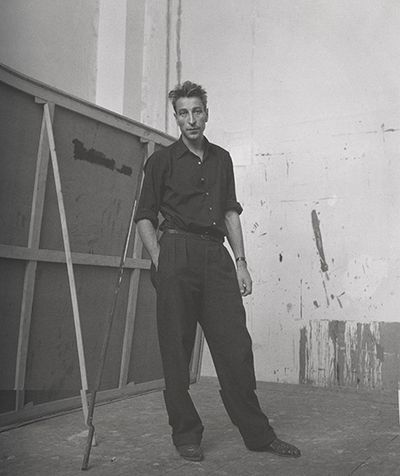

Marc Chagall described him as “innocent” but “with a cosmic force”. That force is clearly visible in photographs of this most charismatic of painters (above). In fact, if one wanted to think of the ideal of the male artist of the second half of the twentieth century, I think he would look like Staël: an imposing 1m 96 (the solidly built and boulder-headed Char was himself over 1m 90), slim and with an angular face, “gifted with the look of an enchanted bird of prey” in Greilsamer’s words, not for nothing was he known as “the Prince”. Picasso, on first meeting him, looked up and was said to have exclaimed: “Prenez-moi dans vos bras”.

“I know that my life will be a continual voyage on an uncertain sea”, Staël wrote to a friend in 1937. He certainly worked hard, producing 266 works in his final year and, according to Mark Hutchinson, in a TLS review of a Staël retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in 2003 (May 16, 2003), some “700 canvases in three years”!

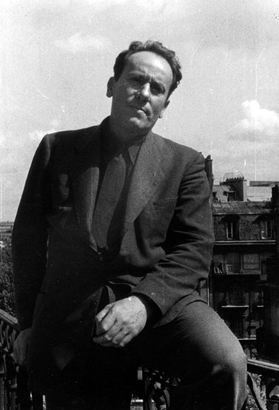

Hutchinson has just published a new translation of Char’s Feuillets d’Hypnos as Hypnos (79pp. Seagull. £14.50/$21 – to be reviewed in a forthcoming TLS). The book, which, in Hutchinson’s words, “is quite unlike any other book written about the French Resistance”, is based on journals the poet kept during the war, in which he was active as a regional leader, code name Alexandre. (The book was translated into German by Paul Celan.) Mixed in with the aphorisms and fragments characteristic of Char’s often difficult work are some acerbic observations on false heroes of the Resistance: “For every Joseph Fontaine, who has the rectitude and tenor of a ploughman’s furrow, . . . how many elusive charlatans there are . . . . You can be sure that, come the liberation, these cocks of oblivion will be crowing loudly in our ears”.

It’s impossible not to wonder about what drove Staël to suicide. We know that he had become infatuated with a woman called Jeanne – “Je l’aime à crever”, he wrote, alarmingly, to Char. Hutchinson wrote of how he “was living apart from a wife and family he adored but could not live with, tormented by an impossible love affair and racked by doubts about the new direction his painting had taken”. Hutchinson talks of the “palpable melancholy that hangs over so many of his last works”, including the “lumbering” seagulls (above), of which the biographer of Picasso, John Richardson, wrote: “in retrospect, it is easy to see that this painting was a cry for help”. Added to which, Staël was, understandably, exhausted.

Many years later, Char wrote of him, beautifully but rather untranslatably: “Nicolas de Staël, nous laissant entrevoir son bateau imprécis et bleu, repartit pour les mers froides, celles dont il s’était approché, enfant de l’étoile polaire”. It’s hard not to think of the “mers froides” as those lapping his native Russia.

The catalogue to the Le Havre exhibition concludes with a short essay by the painter’s son Gustave de Staël who was five when his father died. He describes the studio he left behind, with its vast, “untransportable” and “unfinished” works. Of the family Staël left behind, Gustave writes: “We were . . . linked by so many unanswerable questions”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers