Building the Shack

I’m out in the shack this morning, working on an essay about birds I have seen here. thought I would re-post this piece from the week I built this place:

Robinson Jeffers took eight years to build his stone home, Tor House ,and the adjacent Hawk Tower, both built out of granite and poised on a Big Sur cliff. Mary Oliver’s account of building the cabin behind her Cape Cod home, in Winter Hours, describes no less than a spiritual journey.

As for me, I slammed my writing shack together last weekend.

To each his or her own.

I’m a pretty fast writer and it turns out I’m a pretty fast shack builder, too. But while I may harbor secret dreams of being the greatest writer of all time, I have no such delusions about my carpentry. For one thing I’m not so keen on the whole angles and numbers thing, and while a surprising amount of things in my new shack are level, there are also plenty of things that aren’t. (This writing desk, I’m noticing, as I type this post– my very first shack production by the way– leans to starboard.) One of the main things a young writer learns is that they are not going to be able to support themselves by writing, and my fist attempt at solving that economic problem was by working as a carpenter (a carpenter’s helper really) in Boston and on Cape Cod. I was pretty bad at it, and remarkably insecure when among my more practical co-workers, but some things eventually sank in. What mostly sank in were the slamming, athletic aspects during one winter framing houses on Cape Cod, where moving fast was not just required by my semi-sadistic bosses but by the bracing (a too nice word) weather. In short, I got pretty good at hammering 2 by 4s together.

One of the secrets that house builders know is how fast frames go up, basically going from nothing to house in a few short weeks. Then the finish work starts and goes on forever. When I started writing I was a perfectionist, not showing my work to anyone and taking about five years each to finish my two unpublished novels. I might not have written them at all if I hadn’t learned from framing that the rough draft, the hull of a thing, can be muscled together pretty quick. I also admired one of my bosses, a calm man who showed me a different way to be in the world than my grumbling, judgmental father (and his wrought up Van Gogh of a son).

One of the secrets that house builders know is how fast frames go up, basically going from nothing to house in a few short weeks. Then the finish work starts and goes on forever. When I started writing I was a perfectionist, not showing my work to anyone and taking about five years each to finish my two unpublished novels. I might not have written them at all if I hadn’t learned from framing that the rough draft, the hull of a thing, can be muscled together pretty quick. I also admired one of my bosses, a calm man who showed me a different way to be in the world than my grumbling, judgmental father (and his wrought up Van Gogh of a son).

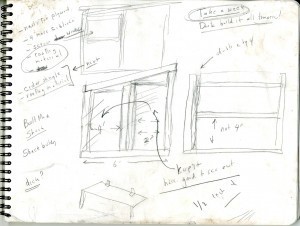

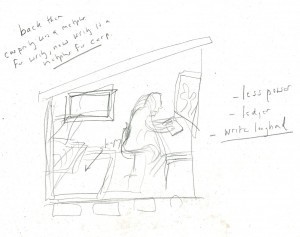

If back then I saw carpentry as a metaphor for writing, this past week I used writing as a metaphor for carpentry. When I set out to build the shack, there were more than a few practical problems, problems that I had no idea how I was going to surmount. I had vowed not to write for the week and the night before I started I did the same thing I often do while writing: woke up at 3 and had ideas. Only these weren’t words, but little drawings in my sketchbook, drawings of what I would build the next day. Then I did something I would never do as a young man. I walked into Home Depot and schmoozed and brainstormed with the people there, who helped me solve a couple of problems. And I solved some problems on my own: like using a screen door turned sideways for the  window I’m looking out right now, giving me a spectacular view of the marsh. (This website actually helped solve another problem: I wasn’t looking forward to building a crowned roof and then remembered the picture of John Hay’s slanted study roof {that I posted here.}) Pretty soon I was into it. “You’re good at getting immersed,” my wife said, which made me proud. It didn’t take long to see that the shack would be a special place for work, even though at that point the only work I’d done was with hammer and nails.

window I’m looking out right now, giving me a spectacular view of the marsh. (This website actually helped solve another problem: I wasn’t looking forward to building a crowned roof and then remembered the picture of John Hay’s slanted study roof {that I posted here.}) Pretty soon I was into it. “You’re good at getting immersed,” my wife said, which made me proud. It didn’t take long to see that the shack would be a special place for work, even though at that point the only work I’d done was with hammer and nails.

I used no power tools and no screws except for the door: just my old framing hammer, some galvanized common nails and coated sinkers, and a handsaw. This was not born wholly out of Thoreauvian idealism. Earlier in the week I bought a power saw at Sears and then discovered, upon opening the box, that some assembly was required,–notably the blade was not attached. I might have gained some confidence in my practical abilities over the last couple of days but I would never, as long as I live, trust a saw on which David Gessner had put the blade. It required a little extra work to do it all by hand, but I still have all my typing fingers.

This morning I brought my bird books, binoculars and telescope down to the shack. The delights here are constant. Clapper rails and herons and egrets. Lots of bluebirds too. The day before my 50th birthday we put up a bluebird house and had bluebirds inside it the next day. Two days later we saw a pileated woodpecker in the yard. The highlight in the shack so far was watching a stark white northern harrier, looking like it had stolen a gannet’s colors, as it hunted, mowing along the top of the marsh grass.

“We need a backshop all our own,” wrote Montaigne. I’ve always been a lover of studies and if you get me started on the subject a certain cabin back in Concord the only way to stop me is to put a plastic bag over my head. One of the fascinating things about Thoreau’s shack was how it solved practical and artistic and personal problems, giving him not just a place to live cheaply, but his subject and a way to be. I don’t expect as much from this place but you never know. Right now my computer battery is running out and so must this post. My plan is to keep this place primitive and have no electricity or plumbing. But there’s a rumor that Bill Roorbach, he of the world famous Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, might be visiting soon and I’ve read that as a young writer/musician he solved some of his own economic challenges working as a plumber and electrician. So who knows? This morning the possibilities, like the view, seem endless.

Bonus pics: