Sur le Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 7

Continued from Part VI:

Keith and I set out on the seventh stage of our journey down Bayou Teche on November 3, 2012, at 9:40 a.m., starting from where we left off last time just south of Franklin. The morning temperature was 57 °F; the afternoon temperature, a balmy 84 °F.

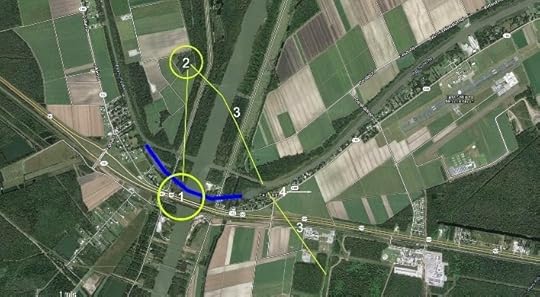

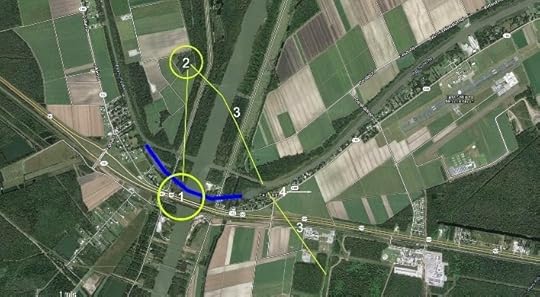

Aerial photograph of stage 7,

Aerial photograph of stage 7,

Far side of Franklin to Calumet.

(Click to enlarge)

(Source: Google Maps)

We shortly spotted a narrow channel running west from the Teche — the Hanson Canal and Lock (29.77261, -91.483286), "[b]uilt in 1907 by the Hanson Lumber Company," according to research by the American Canal Society, "to float log booms from the delta into Bayou Teche." (By "the delta" I assume the ACS meant that of the nearby Atchafalaya River.) In 1922 Hanson Lumber Company sold the lock to the U.S. government, which entrusted its operation to the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1959 the federal government abandoned the lock, which now sits frozen in the "open" position as a vestige of the Teche region's once prosperous but now extinct logging industry.

By 10 a.m. the sun reflected blindingly off the water. We paddled past suburban homes on the west bank, forest on the east. A glance at an aerial photograph, however, revealed that just beyond that wildwood lay enormous swathes of sugarcane. It was already the beginning of harvest and that cane would shortly be cut and ground, its extract boiled and reboiled and processed into raw granulated sugar.

Fishing camp on the Teche that day.

Fishing camp on the Teche that day.

(Photograph by author)

An increasing number of suburban homes on the west bank meant we approached Garden City (29.765279, -91.465889), a community of several dozen houses and a few industrial buildings. Like Franklin, Garden City makes a short appearance in the classic counterculture movie Easy Rider. By "short" I mean three seconds. Those three seconds show an American flag hanging from a whitewashed, wood-framed U.S. Post Office. Although no longer a public building, the structure still stands, with an American flag hanging from the exact same spot as shown in the movie. This flag went up not too long ago, and if I had to guess I'd say the building's current owner hung it there as a paean to Easy Rider.

The old boiler.

The old boiler.

(Photograph by author)

Around 10:20 a.m. Keith and I reached Frances Plantation, whose Creole-style "big house," built around 1810, stands on the west bank. In the bayou almost directly across from the house Keith and I spotted a rusty iron boiler (29.767817, -91.463067) half sunken amid a stand of cord grass. Paddling over to the artifact, we eyeballed it at about four feet in diameter and about twelve feet in length. Although it could have originated in a sugarhouse, we believe it came from a steamboat — and that the spot on which it sat encompassed the wreck of a steamboat. We came to this conclusion because several pairs of large iron bolts protruded from the Teche, running in tandem from the boiler toward a few sheets of corroded iron several yards away. A metal cable rested atop these sheets like a dark sunning snake. Using our canoe as a yardstick, Keith and I measured this chain of presumably related artifacts — the boiler, the pairs of bolts, the sheets of metal, the cable — and altogether they extended about 85 feet along the waterway: the length of a modest-sized steamboat.

Sheets of corroded iron near boiler.

Sheets of corroded iron near boiler.

(Photograph by author)

Later I queried local history enthusiasts about these artifacts and checked inventories of known sunken vessels on the bayou. No one knew anything about them, nor did they appear on the 1870 survey of the Teche, even though it noted every visible obstruction on the bayou (down to individual stumps and logs). This suggested the boiler and other artifacts date to after the 1870 survey. Regardless, the identity of this steamboat — if that’s indeed what it is — remains a mystery.

Frances Plantation from the bayou.

Frances Plantation from the bayou.

(Photograph by author)

After documenting these artifacts, Keith and I paddled farther down the Teche and soon reached Centerville (29.75987, -91.428401) and right beyond it the community of Verdunville (29.75402, -91.401114). Suburban houses stood on both banks. Here we spotted many scattered juglines using cabbage-sized Styrofoam balls as "bobbers." We soon caught up with a motorboater checking these lines; he proudly informed us he’d caught 20 blue catfish so far that day.

Juglines on the Teche that day.

Juglines on the Teche that day.

(Photograph by author)

After a short distance Keith noticed the western side of the bayou had become very shallow. Sticking his paddle into the hazy water, he touched bottom only about a foot below the surface. Spindly bamboo poles rose from the Teche along this stretch, apparently outlining the shoal for unfamiliar boaters. Aerial photographs indicate that when the bayou is low this shoal becomes a lengthy batture(which, as I mentioned previously, refers to marshy land between the water’s edge and the bank of the bayou).

Bamboo poles marking the shoals.

Bamboo poles marking the shoals.

(Photograph by author)

We soon noticed shoals on both sides of the Teche and, sprouting from the shoals’ slimy mud, fingers of aquatic plants twisting in the current like seaweed.

The Teche around Verdunville when low.

The Teche around Verdunville when low.

Note the batture takes up nearly half the riverbed in this image.

When we canoed it, about a foot of water covered this batture.

(Photograph by author)

Around noon we passed the mouth of the Verdunville Canal (29.756218, -91.398575), which runs northeast a short distance to the Atchafalaya Basin Levee. Within sight of the canal the Teche dips southward toward Ricohoc and Calumet, clusters of houses taking their names from local sugar plantations.

About 1 pm Keith and I steered left at a fork in the bayou (29.705574, -91.378969), paddled our canoe through the open west flood gate, and entered the wide expanse of the Wax Lake Outlet.

The fork in the bayou.

The fork in the bayou.

(Photograph by author)

Located directly between Ricohoc and Calumet, Wax Lake Outlet (29.701511, -91.372482), sometimes also called the Calumet Cut, is a massive man-made channel. Completed in the early 1940s by the Army Corps of Engineers, the Outlet runs about sixteen miles in length and stretches roughly six hundred feet in width. It was designed to spare Morgan City from floods by diverting water from the Atchafalaya River to the nearby Gulf of Mexico. The Corps drove the Outlet across the path of the Teche and, unfortunately, through the remains of the Civil War redoubt known as Camp Bisland (located as best I can tell around 29.700355,-91.373905) — thus demonstrating the need for environmental impact studies. (If by chance the the Outlet did not plow right through the fort, the ruin nonetheless would have ended up buried beneath the monumental levee that shadows the Outlet.)

Battle of Bisland (approximate locations):

Battle of Bisland (approximate locations):

1) Fort Bisland;

2) smaller redoubt (connected to fort by trench);

3) Confederate forward entrenchments.

Blue line shows original course of Teche.

Union attacked from northeast following bayou.

(Click to enlarge)

(Source: Google Maps)

The Corps also diverted about a one-mile stretch of the Teche, damming up the bayou’s natural bend at Ricohoc/Calumet and replacing it with a straight detour through two modern flood gates. (I have been educated about these structures by a venerable boat builder of the region: they are not locks, as I initially took to calling them, because they have no chambers in which to raise and lower the water level; rather, they are flood gates, which close when swelling water in the Outlet threatens to deluge the Teche.)

West flood gate on the Teche at Wax Lake Outlet.

West flood gate on the Teche at Wax Lake Outlet.

(Photograph by author)

The Louisiana Highway Department had previously run Highway 90 through the same narrow neck of high land — the natural Teche Ridge — so that today the Outlet, detour, flood gates, and highway (as well as a preexisting railroad) all nearly come together at a single point. It had to be this way, because except for this ridge the entire area is flood-prone cypress swamp. This is why the Confederates erected Fort Bisland on this spot: it presented an easily defendable bottleneck along the course of the Teche.

Looking up the Wax Lake Outlet

Looking up the Wax Lake Outlet

as we paddled across it.

(Photograph by author)

After the narrowness of the Teche, the Wax Lake Outlet seemed vast like the Mississippi River. Yet we could see on the opposite bank, not too far ahead, the open east flood gate and, beyond it, the continuing path of the Teche.

This crossing had worried me for months. As I noted in a previous entry, the Outlet’s current could be treacherous. In fact, the annual Tour du Teche canoe, kayak, and pirogue race posts "safety boats" in the Outlet in case contestants run into trouble — the only place it does so for the entire 135-mile course. Race officials also permit contestants to opt out of crossing the Outlet, without penalty, should they find the passage too dangerous. As a local newspaper reported, "Wax Lake Outlet is the most daunting single obstacle in the Tour. . . . With a sometimes raging current, [it] is nothing to trifle with."

Fortunately, the Outlet was subdued that day, and Keith and I cruised across it as though it didn’t even exist. We encountered turbulence only around the two flood gates, where the waters of the Teche and the Outlet converged. There we saw roiling eddies and little whirlpools that swirled into and out of existence. Making strong, deliberate strokes, we paddled through these eruptions and shortly glided into smoother water.

On the Teche again,

On the Teche again,

beyond the east flood gate.

(Photograph by author)

Again we came to a fork (29.701026, -91.364292). The right, we knew, was the old channel, now a dead end; the left, however, led farther down the Teche. We steered the latter course and looked for a place to stop for the day. Keith and I had planned to stop at the east floodgate — but we unexpectedly found the banks fenced off by the parish and federal governments. So instead we plowed through a mass of reeds and hyacinths to stop at an empty lot next to a house on the east bank. Beyond the lot and house ran Highway 182, which led back to our homes far up the Teche.

We covered a little more than 10.75 miles that day in about 3.75 hours.

While Keith unloaded our supplies I walked to the house to ask if we could cross the lot to reach the highway.

Permission granted.

As I returned to the canoe I did something I would later regret: using my cell phone I photographed a "For Sale" sign in front of the house. It gave the homeowner’s phone number, which I would need in order to ask permission to start our next and final leg from same adjoining lot. (More about this later.)

Keith and I awaited our ride on the side of the road at Calumet, our backs to the bayou. To our front stood a wide plain covered entirely in stalks of ripe sugarcane.

Site of the Battle of Bisland,

Site of the Battle of Bisland,

Calumet, Louisiana.

(Photograph by author)

We were, however, in the middle of the Fort Bisland battleground (approximately 29.702517, -91.350302). The fort, as I mentioned, had been destroyed by the digging of the Wax Lake Outlet — yet most of the fighting had actually occurred about a mile east of the stronghold. Right where we stood. If Keith and I had materialized at that exact spot 149 years earlier, we would have been blown away by shell, shot, and minie balls fired by either combatant. Despite the Outlet, the highway, and the other modern improvements at Ricohoc/Calument, the battlefield proper remains, now as then, planted in cane, and would have looked much the same to the soldiers in the furrows and trenches as it did to us.

How many scattered bones had we paddled over, I wondered? How many shell fragments and cannon balls and railroad iron blasted from lumbering field pieces or from the gunboats Diana and Cotton?

It is well-known among local Civil War buffs that this cane field, like those upstream at Irish Bend, has yielded countless relics over the generations: buttons, belt buckles, coins, an array of projectiles. A few months ago, while driving this same stretch of highway, I spotted a construction crew excavating a large hole on the battlefield's edge. I stopped and audaciously asked the hard-hatted workers if I might examine the spoil. Sure, go ahead, they said, knocking off for lunch and leaving me alone to poke around in the newly exhumed dirt. Surely I would find some artifacts, I thought — a cannonball or a shell fragment, or maybe a cache of unspent bullets.

Artifacts I found at Bisland site.

Artifacts I found at Bisland site.

The largest is about the size of a quarter.

(Photograph by author)

All I found were two decorated ceramic shards, nineteenth-century in appearance. Well, perhaps they had been part of an officer’s mess? Perhaps.

Keith and I set out on the seventh stage of our journey down Bayou Teche on November 3, 2012, at 9:40 a.m., starting from where we left off last time just south of Franklin. The morning temperature was 57 °F; the afternoon temperature, a balmy 84 °F.

Aerial photograph of stage 7,

Aerial photograph of stage 7,Far side of Franklin to Calumet.

(Click to enlarge)

(Source: Google Maps)

We shortly spotted a narrow channel running west from the Teche — the Hanson Canal and Lock (29.77261, -91.483286), "[b]uilt in 1907 by the Hanson Lumber Company," according to research by the American Canal Society, "to float log booms from the delta into Bayou Teche." (By "the delta" I assume the ACS meant that of the nearby Atchafalaya River.) In 1922 Hanson Lumber Company sold the lock to the U.S. government, which entrusted its operation to the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1959 the federal government abandoned the lock, which now sits frozen in the "open" position as a vestige of the Teche region's once prosperous but now extinct logging industry.

By 10 a.m. the sun reflected blindingly off the water. We paddled past suburban homes on the west bank, forest on the east. A glance at an aerial photograph, however, revealed that just beyond that wildwood lay enormous swathes of sugarcane. It was already the beginning of harvest and that cane would shortly be cut and ground, its extract boiled and reboiled and processed into raw granulated sugar.

Fishing camp on the Teche that day.

Fishing camp on the Teche that day.(Photograph by author)

An increasing number of suburban homes on the west bank meant we approached Garden City (29.765279, -91.465889), a community of several dozen houses and a few industrial buildings. Like Franklin, Garden City makes a short appearance in the classic counterculture movie Easy Rider. By "short" I mean three seconds. Those three seconds show an American flag hanging from a whitewashed, wood-framed U.S. Post Office. Although no longer a public building, the structure still stands, with an American flag hanging from the exact same spot as shown in the movie. This flag went up not too long ago, and if I had to guess I'd say the building's current owner hung it there as a paean to Easy Rider.

The old boiler.

The old boiler.(Photograph by author)

Around 10:20 a.m. Keith and I reached Frances Plantation, whose Creole-style "big house," built around 1810, stands on the west bank. In the bayou almost directly across from the house Keith and I spotted a rusty iron boiler (29.767817, -91.463067) half sunken amid a stand of cord grass. Paddling over to the artifact, we eyeballed it at about four feet in diameter and about twelve feet in length. Although it could have originated in a sugarhouse, we believe it came from a steamboat — and that the spot on which it sat encompassed the wreck of a steamboat. We came to this conclusion because several pairs of large iron bolts protruded from the Teche, running in tandem from the boiler toward a few sheets of corroded iron several yards away. A metal cable rested atop these sheets like a dark sunning snake. Using our canoe as a yardstick, Keith and I measured this chain of presumably related artifacts — the boiler, the pairs of bolts, the sheets of metal, the cable — and altogether they extended about 85 feet along the waterway: the length of a modest-sized steamboat.

Sheets of corroded iron near boiler.

Sheets of corroded iron near boiler.(Photograph by author)

Later I queried local history enthusiasts about these artifacts and checked inventories of known sunken vessels on the bayou. No one knew anything about them, nor did they appear on the 1870 survey of the Teche, even though it noted every visible obstruction on the bayou (down to individual stumps and logs). This suggested the boiler and other artifacts date to after the 1870 survey. Regardless, the identity of this steamboat — if that’s indeed what it is — remains a mystery.

Frances Plantation from the bayou.

Frances Plantation from the bayou.(Photograph by author)

After documenting these artifacts, Keith and I paddled farther down the Teche and soon reached Centerville (29.75987, -91.428401) and right beyond it the community of Verdunville (29.75402, -91.401114). Suburban houses stood on both banks. Here we spotted many scattered juglines using cabbage-sized Styrofoam balls as "bobbers." We soon caught up with a motorboater checking these lines; he proudly informed us he’d caught 20 blue catfish so far that day.

Juglines on the Teche that day.

Juglines on the Teche that day.(Photograph by author)

After a short distance Keith noticed the western side of the bayou had become very shallow. Sticking his paddle into the hazy water, he touched bottom only about a foot below the surface. Spindly bamboo poles rose from the Teche along this stretch, apparently outlining the shoal for unfamiliar boaters. Aerial photographs indicate that when the bayou is low this shoal becomes a lengthy batture(which, as I mentioned previously, refers to marshy land between the water’s edge and the bank of the bayou).

Bamboo poles marking the shoals.

Bamboo poles marking the shoals.(Photograph by author)

We soon noticed shoals on both sides of the Teche and, sprouting from the shoals’ slimy mud, fingers of aquatic plants twisting in the current like seaweed.

The Teche around Verdunville when low.

The Teche around Verdunville when low.Note the batture takes up nearly half the riverbed in this image.

When we canoed it, about a foot of water covered this batture.

(Photograph by author)

Around noon we passed the mouth of the Verdunville Canal (29.756218, -91.398575), which runs northeast a short distance to the Atchafalaya Basin Levee. Within sight of the canal the Teche dips southward toward Ricohoc and Calumet, clusters of houses taking their names from local sugar plantations.

About 1 pm Keith and I steered left at a fork in the bayou (29.705574, -91.378969), paddled our canoe through the open west flood gate, and entered the wide expanse of the Wax Lake Outlet.

The fork in the bayou.

The fork in the bayou.(Photograph by author)

Located directly between Ricohoc and Calumet, Wax Lake Outlet (29.701511, -91.372482), sometimes also called the Calumet Cut, is a massive man-made channel. Completed in the early 1940s by the Army Corps of Engineers, the Outlet runs about sixteen miles in length and stretches roughly six hundred feet in width. It was designed to spare Morgan City from floods by diverting water from the Atchafalaya River to the nearby Gulf of Mexico. The Corps drove the Outlet across the path of the Teche and, unfortunately, through the remains of the Civil War redoubt known as Camp Bisland (located as best I can tell around 29.700355,-91.373905) — thus demonstrating the need for environmental impact studies. (If by chance the the Outlet did not plow right through the fort, the ruin nonetheless would have ended up buried beneath the monumental levee that shadows the Outlet.)

Battle of Bisland (approximate locations):

Battle of Bisland (approximate locations):1) Fort Bisland;

2) smaller redoubt (connected to fort by trench);

3) Confederate forward entrenchments.

Blue line shows original course of Teche.

Union attacked from northeast following bayou.

(Click to enlarge)

(Source: Google Maps)

The Corps also diverted about a one-mile stretch of the Teche, damming up the bayou’s natural bend at Ricohoc/Calumet and replacing it with a straight detour through two modern flood gates. (I have been educated about these structures by a venerable boat builder of the region: they are not locks, as I initially took to calling them, because they have no chambers in which to raise and lower the water level; rather, they are flood gates, which close when swelling water in the Outlet threatens to deluge the Teche.)

West flood gate on the Teche at Wax Lake Outlet.

West flood gate on the Teche at Wax Lake Outlet.(Photograph by author)

The Louisiana Highway Department had previously run Highway 90 through the same narrow neck of high land — the natural Teche Ridge — so that today the Outlet, detour, flood gates, and highway (as well as a preexisting railroad) all nearly come together at a single point. It had to be this way, because except for this ridge the entire area is flood-prone cypress swamp. This is why the Confederates erected Fort Bisland on this spot: it presented an easily defendable bottleneck along the course of the Teche.

Looking up the Wax Lake Outlet

Looking up the Wax Lake Outletas we paddled across it.

(Photograph by author)

After the narrowness of the Teche, the Wax Lake Outlet seemed vast like the Mississippi River. Yet we could see on the opposite bank, not too far ahead, the open east flood gate and, beyond it, the continuing path of the Teche.

This crossing had worried me for months. As I noted in a previous entry, the Outlet’s current could be treacherous. In fact, the annual Tour du Teche canoe, kayak, and pirogue race posts "safety boats" in the Outlet in case contestants run into trouble — the only place it does so for the entire 135-mile course. Race officials also permit contestants to opt out of crossing the Outlet, without penalty, should they find the passage too dangerous. As a local newspaper reported, "Wax Lake Outlet is the most daunting single obstacle in the Tour. . . . With a sometimes raging current, [it] is nothing to trifle with."

Fortunately, the Outlet was subdued that day, and Keith and I cruised across it as though it didn’t even exist. We encountered turbulence only around the two flood gates, where the waters of the Teche and the Outlet converged. There we saw roiling eddies and little whirlpools that swirled into and out of existence. Making strong, deliberate strokes, we paddled through these eruptions and shortly glided into smoother water.

On the Teche again,

On the Teche again,beyond the east flood gate.

(Photograph by author)

Again we came to a fork (29.701026, -91.364292). The right, we knew, was the old channel, now a dead end; the left, however, led farther down the Teche. We steered the latter course and looked for a place to stop for the day. Keith and I had planned to stop at the east floodgate — but we unexpectedly found the banks fenced off by the parish and federal governments. So instead we plowed through a mass of reeds and hyacinths to stop at an empty lot next to a house on the east bank. Beyond the lot and house ran Highway 182, which led back to our homes far up the Teche.

We covered a little more than 10.75 miles that day in about 3.75 hours.

While Keith unloaded our supplies I walked to the house to ask if we could cross the lot to reach the highway.

Permission granted.

As I returned to the canoe I did something I would later regret: using my cell phone I photographed a "For Sale" sign in front of the house. It gave the homeowner’s phone number, which I would need in order to ask permission to start our next and final leg from same adjoining lot. (More about this later.)

Keith and I awaited our ride on the side of the road at Calumet, our backs to the bayou. To our front stood a wide plain covered entirely in stalks of ripe sugarcane.

Site of the Battle of Bisland,

Site of the Battle of Bisland,Calumet, Louisiana.

(Photograph by author)

We were, however, in the middle of the Fort Bisland battleground (approximately 29.702517, -91.350302). The fort, as I mentioned, had been destroyed by the digging of the Wax Lake Outlet — yet most of the fighting had actually occurred about a mile east of the stronghold. Right where we stood. If Keith and I had materialized at that exact spot 149 years earlier, we would have been blown away by shell, shot, and minie balls fired by either combatant. Despite the Outlet, the highway, and the other modern improvements at Ricohoc/Calument, the battlefield proper remains, now as then, planted in cane, and would have looked much the same to the soldiers in the furrows and trenches as it did to us.

How many scattered bones had we paddled over, I wondered? How many shell fragments and cannon balls and railroad iron blasted from lumbering field pieces or from the gunboats Diana and Cotton?

It is well-known among local Civil War buffs that this cane field, like those upstream at Irish Bend, has yielded countless relics over the generations: buttons, belt buckles, coins, an array of projectiles. A few months ago, while driving this same stretch of highway, I spotted a construction crew excavating a large hole on the battlefield's edge. I stopped and audaciously asked the hard-hatted workers if I might examine the spoil. Sure, go ahead, they said, knocking off for lunch and leaving me alone to poke around in the newly exhumed dirt. Surely I would find some artifacts, I thought — a cannonball or a shell fragment, or maybe a cache of unspent bullets.

Artifacts I found at Bisland site.

Artifacts I found at Bisland site.The largest is about the size of a quarter.

(Photograph by author)

All I found were two decorated ceramic shards, nineteenth-century in appearance. Well, perhaps they had been part of an officer’s mess? Perhaps.

Published on April 19, 2014 22:21

No comments have been added yet.