Four Perspectives on One F**ked-Up Little Piece

PART I: HER

Juilliard, 1967: She walks into the audition room, her hair as black as the piano waiting at its center. A panel of faculty says nothing, gestures nothing. Like the piano, they just wait. She sits at the instrument—the lid raised, no desk for music, only terrifyingly open space exposing a golden inner body and copper strings extending nine feet ahead, incarcerating the white hammers below them, ready to strike, waiting. Inwardly, she scans the names of the composers whose music she has prepared. Beethoven. Bach. Chopin. Khachaturian.

Her father, an Armenian (last name Minassian) who fled Turkey in the years surrounding the Genocide, who raised both she and her sister after their mother (last name Kassabian) passed away, was also her piano teacher. He coached her mercilessly, with celebrations to reward her successes and guilt trips that could last for days to punish her failures. He hand picked her audition program, and though he was no fan of modern music, his daughter, a full-blooded Armenian, would play an Armenian composer. Khachaturian would appear alongside the great classical titans, as strange as his Toccata might sound. When family visited—all Armenian—he would march her before them. “Play the Khachaturian.”

"Play the Khachaturian," says a voice. Is it real? It comes from either a few feet away or a mile. Her mind feels tethered to her father, wherever he’s waiting, and the thick fog of expectancy he inhabits. A self-taught pianist himself, he wanted his daughter to receive the fabled Juilliard training he never had, to realize his unfulfilled dream of becoming a concert pianist.

"Or you can begin with something else," that same voice says.

But the voice doesn’t know that all of the music has disappeared into that fog. These names—Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, Khachaturian—are now only names, tabs on suddenly empty folders. Ice surges from her heart to her stomach, from the tops of her thighs to the tips of her fingers. The room tilts, darkens. Her breath quickens. She can barely see the glow of the strings anymore or the whites and blacks of all those foreign, meaningless keys. Instead, she sees a montage of family gatherings, her father leaning against the living room wall watching as she dutifully plays the Khachaturian. She tries to go deeper, to seize some sensory element, something to capture and bring back to this nightmare moment, something she can use. But it’s watching a silent movie, and right now it may as well be about someone else. She can’t recognize herself then, nor herself now, frozen at the keyboard.

But the music has disappeared into that fog of expectancy. These names—Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, Khachaturian—are only names, tabs on suddenly empty folders. Ice surges from her heart to her stomach, from the tops of her thighs to the tips of her fingers. She room tilts, darkens. Her breath quickens. She can barely see the glow of the strings anymore, or the whites and blacks of all those foreign, meaningless keys. Instead, she sees a montage of family gatherings, her father against the living room watching as she dutifully plays the Khachaturian. She tries to go deeper, to squeeze some sensory element to capture and and reclaim and bring back to this nightmare moment, but it’s a silent movie, and right now it may as well be about someone else. She can’t recognize herself then, nor can she recognize herself now, frozen at the keyboard.

Play the Khachaturian, she says to herself. Play the Khachaturian.

But she doesn’t. She stands up and walks out. Out of the room. Out to another life completely. In this new life, she becomes an elementary school teacher, marries and divorces her high school sweetheart, and alone raises their three kids in Vermont. Two girls, and one boy.

PART II : OUR

Many pianists snicker at the mention of Khachaturian’s Toccata from 1932. It was training wheels for some in the new music community, and conversely, as modern as many some others would ever get.

Like a riptide, the Toccata has dragged many a pianist into the world of modern music; they view it as an old friend. ”I love the Toccata,” a pianist idol of mine said recently. “It was my first modern-sounding piece, and totally opened my mind.” A composer I talked to who played the piece when he was 15 years old (over sixty years ago) called it “visceral music,” and Khachaturian not only “an icon of the major seventh” (referring maybe to the Sabre Dance), but as the black sheep of his intellectual Soviet contemporaries. “He was the ‘n****r’ of the group,” he said. I gasped. “And he knew they thought that.”

Well, whatever his colleagues thought, Khachaturian had the biggest blockbusters of the bunch. The ballets, from Gayne to Masquerade to Spartacus, were all triumphs. His Violin Concerto is still a standard (often even played by flutists), and the Piano Concerto became a virtual jukebox hit after William Kapell championed it. And yes, the Toccata, our subject, is pretty ubiquitous amongst pianists. It seems nearly everyone has played it.

This doesn’t do it any incredible favors. “It’s such a student piece!” a colleague noted. One former-pianist (now he plays bass) told me that he’d performed the Toccata as a kid. “You look at your hands and you’re like, ‘woah, I’m good!’ But really it’s pretty easy.” And so it goes. Few would call it a work of art, even if, like most classical music hits, it actually is. No, to many, Khachaturian remains an inelegant, rhythmically driven, “visceral” composer of pop classical music—not his intention, by the way, nor really his fault—and so his music, or at least his Toccata, remains banished to barrooms and student recitals, the regrettable territory of “look what I can do!”

Furthermore, to many Armenian pianists (or non-pianists who suffered lessons through adolescence), the Toccata is almost a rite of passage. In an Armenian household, playing the Toccata of Khachaturian, that Armenian titan of classical music, is almost a non-negotiable. Nevermind that the piece is something of a longing, frenetic, furious nightmare vision.

Yes, nevermind, because amidst all this noise and baggage, the piece almost ceases to exist. Does anyone actually program this Fur Elise of modern music? The answer is kind of no. We might like it, might teach it, might reminisce or wax poetic on its unique qualities, but for the most part, we pianists who dare call ourselves professional won’t dare play this “student piece” in concert.

Too bad, because for one, a lot of these students are out there playing it badly, which is to say, before they’re ready. And while I think that very few people actually ‘get’ it, many would argue with me that there’s anything to get in the first place. They call it child’s play, while I say it’s not for kids.

Might we entertain the notion that Khachaturian’s Toccata was hijacked by its own popularity—the sum of its appealing sound, playability, and cultural positioning? Does anyone else agree that the Toccata, taken by itself, is actually a pretty fucked up little piece?

PART III: THE

Since the late 1500s, toccatas have tested the techniques and interpretive strengths of performers, with composers laying musical gauntlets that, on the whole, were supposed to sound improvised in performance. The toccata form grew from its experimental, single movement and improvisatory origins into a multi-sectional work of great sophistication and emotion by the time Bach composed his own series for organ and harpsichord around 1710. From there, the toccata continued to evolve, coming to represent something of a one movement, moto perpetuo showpiece in the Romantic era, with Robert Schumann’s solo piano Toccata of 1836 setting the bar; he considered it “the hardest piece every written.”

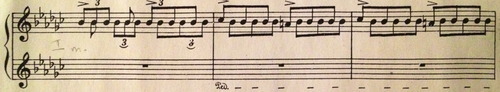

Liszt, Prokofiev, Ravel, and Debussy (oh, and Robert Palmer) among others, followed with solo piano toccatas of their own—all hard as hell. And then of course there was Khachaturian’s of 1932, composed while he was still a student in Moscow. It follows the modern toccata style with its one movement form and dazzling technical passagework, and yet perhaps it harkens back to the earlier toccata formula in that it balances fast fingerwork with emotional depth and sections of varying tempi. Khachaturian’s Toccata, for instance, has at its core a slow, mournful, lyrical section, and on the whole, the cascades of notes in the outer parts seem less about impressing the listener and more aimed at building shimmering, if melancholy, harmonies within what we might now call almost minimalist textures. The rapid-fire B-flats that serve as transitional material splinter with “wrong notes”…

…only to explode into a cosmic soundworld of lilting, incessant, almost baroque-sounding suspensions.

That’s how the dissonance of this piece works, moving away from the percussive, ear-shredding variety we might expect from Khachaturian’s Soviet contemporaries (see Prokofiev’s fiendishly Toccata) and more toward harmonic subtlety. Far from unpleasant—and some might say, too pleasant—the dissonance of this piece serves to bend pitches, drag harmonies down or sharpen them up, an homage perhaps to the Armenian street music Khachaturian grew up hearing, and more-or-less the best he could do with an intonationally inflexible piano.

His Toccata’s heart-on-its-sleeve emotionality, its extroverted panache, and pianist-friendly writing, launched it into the popular canon of modern piano literature, making it something of an instant 20th-century classic, even though Khachaturian actually intended it as part of a three-movement suite, the other movements of which are still relatively unplayed. I’ve never heard them.

PART IV: MY

The Toccata was the first piece of modern piano music I ever heard. An older, Armenian piano student played the piece at an informal studio recital that my teacher put together. I was probably playing "Coke Is It" at the time, but still remember the Toccata completely bowling me over. Its opening march combined harmonies that seemed uncombinable, the thick booming chords that followed shook me to the core, the subsequent flurrying passagework and left hand melodies had me mesmerized, the middle section seemed suspended in time, and most notably, those rapid-fire repeated notes seemed to go on forever.

I didn’t know music like this existed, that piano music could do what the Toccata, in my mind, dared to do. It also sounded hard. Really hard. Even as the piece remained in my mind as some kind of amorphous thing defined by fast notes and that weird section with repeated notes, and even though people told me how “easy” it was, I never played it. Looking back, the first really modern repertoire I ever played was actually ten times harder than the Toccata, music by Prokofiev and Copland. Still, I thought about “the Khachaturian,” with my emotions hovering just about where they were when I was eight years old and listening to it for the first time. “What the hell was that?”

So one day, while visiting home from college and digging through some of my late grandfather’s scores, I found the Toccata tattered and pieced together with ancient Scotch tape. I memorized it in a couple days, and the piece was like a playground, full of clean patterns and aching beauty. I felt like the first person who had ever played it. An explorer. I’d expected mindless fireworks and flash, but instead discovered a subtle tapestry of pathos, pain and drama, echoes of the 1915 Genocide that no doubt had touched Khachaturian’s life and left him feeling, like many generations to come, angry and powerless, not to mention incapable of expressing the chasm of grief it opened.

Only about fifteen scarce years separate the Genocide from the Toccata, and as I played, I could hear it everywhere. I heard rage. I heard cries. I heard reverie. And I told myself that if ever I played it in public, I would play it with as much care and respect as fury and abandon as it merited, a performance washed in the blood of my murdered ancestors and those of a million others.

If ever I played it in public.

But—I mean—of course I wouldn’t. And risk my reputation? No. I abandoned the piece as quickly as I took it on.

That was years ago. Then, a couple of months ago, the AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union) approached me to participate in a concert for previous scholarship recipients at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Hall. Even as a half-Armenian with a Polish last name (and middle name), AGBU supported every year I spent at IU. I accepted the invitation to perform without hesitation. It’s tomorrow, and will be my first time playing in Carnegie Hall. They’ve asked me to play the Toccata.

Talk about chatter. Part of me believes that I have five minutes to represent a hundred generations of Armenian culture. Another part fears that everyone in the audience will know the Toccata note for note and will weigh my (admittedly unique) performance of it against their twelve year old nephew’s. And then finally a part of me feels a tremendous sense of pride, because even if I freeze up whenever a fellow Armenian when a fellow Armenian smiles and says “inchbes es,” this staple of Armenian classical music is, once and for all, finally mine. My Khachaturian.

Armenians by nature have a fierce sense of pride, a symptom, if nothing else, of our tiny country, rich and insular culture, and a history shaped by persecution, mass murder, and the rearrangement of national borders by outside forces. As a kid, I grew quite used to looking at maps and globes that didn’t include Armenia. If someone asked where Armenia was, I’d search a map, apologizing all the way. “Hm, well it might not be here…”

We’ve also earned a reputation for guardedness. We lower our voices when mentioning the atrocities that have come to define our resilience, unless of course someone, or a government for that matter, dares to deny they actually happened. Virtually any Armenian you meet has lost family members to the Genocide—I did—and in a way it still hurts too much to talk about. [For a brilliant look at grief in the Armenian family dynamic, read Peter Balakian’s Black Dog of Fate.]

It might turn out that music is our best way to communicate our grief, and Armenian music indeed has its fair share of minor keys and dissonance, of sour and sweet (in that order). Yes, it might turn out that, instead of discussing our troubled past at the dinner table, we have every Armenian kid who plays piano learn the Khachaturian Toccata and let them tap into that soundworld of rage and sorrow and hysteria for themselves.

We go into the music to connect; that’s where we tell our story.

And in the end, it all collapses onto an unresolved, almost exasperated E-flat-chord (no third; not major or minor) stabbed with a clashing F-flat. Khachaturian asks the pianist to let this chord ring under a fermata, and in the resonance, we’re forced to make some sense of it all.

That, my friends, is how our flashy Armenian showpiece ends. We hope you’re impressed.

[Adam Tendler will perform Khachaturian’s Toccata at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Hall on Saturday, December 7th at 8 p.m.: info here]