Some Observations on the Limitations of Reading Levels

As a teacher, I have used reading levels to match readers with texts. Reading levels are any of the myriad systems developed to evaluate texts for readability. Typically these systems assign a rating or measurement that equals an age or a grade or a number to the text. Thus, we can pick up a paperback, look on its back cover, and discover a reading level included by the publisher that we interpret, “This book has a reading level of 5.4, which means it is readable by a fifth grader in his or her fourth month.” The essential truth about all reading levels is that there is a continuum of complexity that begins with the easiest texts on one end and moves through increasingly complex texts to end with the most complex text. Plotting each text at a point on this continuum allows readers to compare readability between texts.

The thing is, as I deal with reading levels as both an educator and parent, I find that there’s something that nags me as imprecise and, yes, I’m going to say it, wrong about the various reading levels that have been developed and are in use today. Books show up with ratings that just don’t make sense: some books are clearly written for younger readers, but they have very challenging reading levels; or books with adult concepts show up that have very basic reading levels. Over the years, I’ve observed this phenomenon, and what it comes down to is this:

Reading levels are useful tools, but they have limitations.

These limitations are most visible when educators or readers place too much emphasis on reading levels, when they use them as boundaries instead of guidelines, when they embrace reading levels as dogma. This comes out of my own experiences as both a parent and a teacher, from the expectations placed on my own children by other educators, and the expectations I’ve placed on other people’s children in my own classroom.

The two systems for measuring text complexity that I am most familiar with are ATOS, a product of Renaissance Learning, and Lexile, a product of MetaMetrics. Both companies have built their businesses around their unique systems for evaluating reading levels, and both have unique formulae that they use to evaluate text. These systems are different but parallel, and I will refer to both.

First, an acknowledgement: both Renaissance Learning and MetaMetrics know and communicate clearly that reading levels have limitations; they don’t pretend otherwise. It’s at the reader’s end of things where I’ve seem reading levels misinterpreted or misunderstood, either by readers themselves, or by the parents and teachers helping guide their child/students’ reading. Also, I am in no way capable of explaining any of the intricacies of determining reading level: the formulae, the math calculations, the terminology. I think these things may be outside my reading level.

ATOS

So much information has already been shared about ATOS by Renaissance Learning that I would never be able to do a better job explaining it than they already have. Read even a little of the information they have posted at their website and you, too, will begin to appreciate the effort that has gone into creating the ATOS tool for determining readability.

ATOS values are decimal based, with the lowest book level a 0.1 and the highest value a 16.9. The ranges correspond to school years, from Kindergarten (16).

The foundation of the ATOS formula is “the number of words per sentence, average grade level of words, and average characters per word” (Milone, 10). ATOS then takes into account the overall length of the text, recognizing that shorter texts are more readable than longer texts. Further, the formula factors sentence length as it corresponds to overall text length.

ATOS has a substantial amount of data to drive it; Renaissance Learning determines reading levels for its Accelerated Reader program, a subscription web-based product purchased by school districts to provide independent testing on more than 150,000 book titles (See my blog post on using the Accelerated Reader website as a tool to find the word count of published books). Not only has each title been run through an ATOS calculator, but student performance on a test after reading each title is available to Renaissance Learning. This puts Renaissance Learning in a unique position because they can determine a reading level for the text, then compare that reading level to test results from real readers.

A database of every book that has been measured for ATOS is available through www.arbookfind.com. However, shorter texts may be uploaded and analyzed with the ATOS text analyzer.

Lexile

The State of Illinois, in its ISAT results, uses Lexile as the readability measure it connects to student progress. Each child’s ISAT report includes a suggested Lexile range. Rather than use a grade equivalent, MetaMetrics created a continuum from zero through over 1600 to define a text’s readability. According the MetaMetrics, “The Lexile measure is shown as a number with an “L” after it — 880L is 880 Lexile.” While it may be tempting to associate the Lexile continuum as grade levels, this is not the case. A searchable database of books with their measured Lexile scores is available at www.lexile.com. The actual details of the Lexile formula is not publicly available, and any attempt to determine what the Lexile of a book or passage might be that has not come from MetaMetrics is only an estimate or guess because the company uses proprietary formulas to calculate a text’s readability.

Observation #1: Reading Levels Encourage Oversimplification

Because reading levels create concise numeric ratings for books, the tendency for users is to rely too heavily on the measurement without taking into account other information about either the book or the reader that would fall outside the textual information that reading levels are capable of measuring.

How this plays out for educators and readers is that the reading level becomes the first criteria to consider in choosing a title rather than other, intrinsic motivators. For me this is like the proverbial cart before the horse: As a reader, my first consideration is whether or not I want to read the book. With reading levels, interest is secondary; readers select books within a range of readability levels, omitting any exposure to those titles outside that range. Go ahead and walk through a library, try to pick a book from the shelf, experience that serendipity of finding a title with a cover that screams, “Read me!” that you’ve stumbled on by accident in the stacks. Or that book your best friend just stuck into your hands with a quiver in his voice as he told you it was the best book he’s ever read. Oops, those books are outside your Lexile. If you touch them; they’ll burn your fingers.

This oversimplification on the part of users is exacerbated by another factor, specifically…

Observation #2: The formulas used to calculate text complexity do not factor concepts, context, or narrative complexity.

This is especially problematic with fiction texts. Text complexity measures the measurable, like the length of words, words per sentences, sentences per paragraphs, syllables per word, etc. However, texts may include concepts and narrative elements that require inferencing and background knowledge far beyond the scope of the reader’s experiences.

Take, for example, Dune by Frank Herbert. The Hugo and Nebula Award-winner is rated with an ATOS Book Level of 5.7 and a Lexile of 800L. However, Dune posits a far-future empire with Machiavellian intrigues in a complex political and economic power struggle. Power plays between the Emperor and House Atreides, the Bene Gesserit breeding program, the idea of the Spacing Guild and its monopoly on space travel; all of these are conceptually very advanced for a fifth-grade reader. When Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen attempts to assassinate his uncle, the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, he does so by hiding a poisoned needle beneath a patch of artificial skin on the inner thigh of a slave boy. The implications are never elaborated upon by Herbert, who expects his reader to make inferences about the Baron’s proclivities. Dune is, in concept, a robust read, but both the ATOS and Lexile place it in Common Core Grade Band 4-5. My son Alex read it as a fifth grader and did not pass the test.

American Gods by Neal Gaiman is another Hugo and Nebula Award-winner. It rates a 5.3 ATOS Book Level and has no Lexile associated with it. This book covers an amazing assortment of mythological beings from multiple old-world sources. It includes violence. It includes sex. It even includes violent sex. Did I mention that that ATOS would put that in the range of a fifth grader?

The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara is rated at only a 4.7. I am reading it right now to my sons, Alex and Bryan, aged 12 and 10. The sheer number of characters is overwhelming, and this is compounded with the individual histories that each character brings into the story. It’s a brilliant book; one that I think does an exceptional job helping the modern reader understand the complexities that surround war and honor, and especially the American Civil War, which is too easily explained (and too simply understood) as a war over slavery. Shaara is able to delve into the unique psyche of multiple characters from both the North and the South and give his readers nuanced interpretations of why the fight was worth facing death and loss. Fourth grade? No way.

In Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Appendix A: Research Supporting Key elements of the Standards, the authors define a “three-part model for determining how easy or difficult a particular text is to read.” The text then defines three components as

Quantitative: “aspects of text complexity, such as word length or frequency, sentence length, and text cohesion, that are difficult if not impossible for a human reader to evaluate efficiently, especially in long texts, and are thus today typically measured by computer software.” The “Quantitative” component is the reading level of the text.

Qualitative: “aspects of text complexity best measured or only measurable by an attentive human reader, such as levels of meaning or purpose; structure; language conventionality and clarity; an knowledge demands.”

Reader and Task Considerations: “variables specific to particular readers…and to particular tasks must also be considered.”

Thus, of the three components elaborated upon as factors in determining readability, only one focuses on the component we currently call reading level.

Oddly enough, this inability to do more than interpret the “Quantitative” aspect of a text has a very obvious and dramatic consequence for readers because…

Observation #3: Nonfiction “style” earns higher reading levels than fiction “style.”

The formulae cannot distinguish genre or purpose; they can only calculate the measurable components of the text. A reader who is expected to read more challenging books will find that the titles available to him or her are weighted more heavily by non-fiction.

Take a look at the following results pulled from www.arbookfind.com during November, 2013 (the exact number of results will not be reproducible because of the constant addition of new titles to AR’s database of available quizzes, but I would expect the percentages to remain consistent).

Renaissance Learning divides books into four interest levels to help match readers with texts that will be appropriate for their age group:

Lower Grades (LG K-3)

Middle Grades (MG 4-8)

Middle Grades Plus (MG 6 and up)

Upper Grades (UG 9-12)

Using the recommended ATOS Book levels for Common Core, I’ve broken out the total number of English language quizzes based on fiction versus nonfiction. Additionally, I’ve presented both the total quizzes available and the percentages of those quizzes as fiction versus nonfiction.

For the those books with interest levels for grades K-3, the easiest reads are dominated by fiction, and as the text complexity increases, the slant toward nonfiction increases.

Lower Grades (LG K-3)

CCSS Grade BandsRecommended ATOS Book Levels# Fiction# Nonfiction% Fiction% Nonfiction

2nd to 3rd2.75 to 5.1419,18091395%5%

4th to 5th4.97 to 7.031,0254,16720%80%

6th to 8th7.00 to 9.985707%93%

9th to 10th9.67 to 12.0100NANA

11th to CCR11.20 to 14.1000NANA

By the middle grade titles, the slant is even more obvious because the number of titles that match the middle grade interest and readability lean significantly to nonfiction. Look at the 6th to 8th grade band, which is the level I teach; for those books that would interest a middle grade reader, fully 97% are nonfiction. A paltry 330 are fiction. Call me a fiction prude if you like, but I came to my love for nonfiction through fiction. Fiction was my gateway drug. Maybe other people loved nonfiction from the start, but I was a prolific reader of fiction during my middle grade years, and there is nothing in this chart that would have made me into the reader I am today.

Middle Grades (MG 4-8)

CCSS Grade BandsRecommended ATOS Book Levels# Fiction# Nonfiction% Fiction% Nonfiction

2nd to 3rd2.75 to 5.1415,7386,95069%31%

4th to 5th4.97 to 7.037,63218,01830%70%

6th to 8th7.00 to 9.9833010,6033%97%

9th to 10th9.67 to 12.01183545%95%

11th to CCR11.20 to 14.1031517%83%

I’m not really sure about this “Middle Grades Plus” category. I would have assumed that there would be overlap from the “Middle Grades (MG 4-8)” titles, but given the total quiz counts, this doesn’t appear to be true. What hasn’t changed is the absolute dominance of nonfiction over fiction. I am very concerned here because, as a parent, both of my sons have been told that they need to challenge themselves with texts that are at higher reading levels. But look at the total quizzes available: there are only 29 quizzes at the 9th to 10th grade reading level. There are only 363 (45 289 1 28) tests available that are above sixth grade. For this interest level, it’s either all fiction through 5th grade band or all non-fiction after 6th grade band; there is no balance between the two.

Middle Grades Plus (MG 6 and up)

CCSS Grade BandsRecommended ATOS Book Levels# Fiction# Nonfiction% Fiction% Nonfiction

2nd to 3rd2.75 to 5.141,8013098%2%

4th to 5th4.97 to 7.031,45315390%10%

6th to 8th7.00 to 9.984528913%87%

9th to 10th9.67 to 12.011283%97%

11th to CCR11.20 to 14.1000NANA

For those readers who are in the upper grades, the picture is bleak for fiction. There are only 137 (45 61 31) titles to choose from; you better not be a prolific reader after sixth grade because there are only 137 fiction books that will be at your reading level. Another interesting fact is that of the books that would interest an upper grade reader, the vast majority (a whopping 93%) are written at the ATOS 4.97 to 7.03 grade level.

Upper Grades (UG 9-12)

CCSS Grade BandsRecommended ATOS Book Levels# Fiction# Nonfiction% Fiction% Nonfiction

2nd to 3rd2.75 to 5.142861097%3%

4th to 5th4.97 to 7.035,8091,14584%16%

6th to 8th7.00 to 9.98453,3861%99%

9th to 10th9.67 to 12.01611,1425%95%

11th to CCR11.20 to 14.103115816%84%

I can’t tell you why the ATOS formula is slanted toward non-fiction, but Renaissance Learning is well aware of this fact. Indeed, they launched a study to determine differences between fiction and non-fiction for this very reason. Anecdotally, I observed that the age of fiction tends to increase as the reading level increases, so that the most difficult fiction titles fall into those written over one hundred years ago.

All of these observations bring me to my own conclusion, namely…

Conclusion: As reading proficiency increases, the value of reading levels declines

Proficient readers do not need to rely on reading levels. For as far as I can remember I have never in my life consulted a reading level to select a book. Never. Let me repeat: not once at any time in my thirty-nine years of life, including the twelve years I spent in public education and the four years I spent earning my Bachelor’s and the two years I spent getting a Master’s degree have I ever consulted a book’s readability in determining whether I was capable of reading it. If it ever was an important consideration for me, it would have been before fourth grade, when I was a developing reader. Once I became proficient enough to read independently, those boundaries were unnecessary. Like Goldilocks, I knew which porridge was good to eat; some might be too hot, others might be too cold, but some were just right.

I am a proficient reader; my sons Alex and Bryan are proficient readers. I am not concerned that they will have a sudden desire to read Snotty Nose Jones books; they’ve moved on in their tastes, and even if they decide that they want to read books that are beneath them, the books will be so easy that they will move through them quickly and move on. No harm done.

Additionally, the oversimplification of reading levels fails to address this simple truth: Readers’ growth will begin to plateau as they become more and more proficient readers.

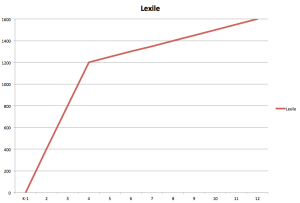

My son Bryan received his fourth grade ISAT test results which included a recommended Lexile range of 1135L to 1235L. Take a look at this chart which I reproduced from Lexile.com:

Revised Lexiles to Match Common Core Grade Bands

CCSS Grade BandsCurrent Lexile Band"Stretch" Lexile Band

2nd to 3rd450L-725L420L-820L

4th to 5th645L-845L740L-1010L

6th to 8th860L-1010L925L-1185L

9th to 10th960L-1115L1050L-1335L

11th to CCR1070L-1220L1185L-1385L

This information puts Bryan’s progress at the very top of the chart — as a fourth grader! What kind of future growth should Bryan’s teachers expect from him? The answer: very little. Bryan is not going to have measurable growth in his reading level for the next eight years of his schooling; his growth will be in the other components of readability: the “Qualitative” and “Reader and Task Considerations” aspects of readability, and neither of these can be determine by mechanical means.

Assuming Bryan is able to go forward from fourth grade and achieve the highest Lexile score (it tops out at 1600) by the time he graduates high school, here is a simplified visual chart to show his anticipated reading level growth over his primary and secondary years:

Notice the plateau? That’s because Bryan’s reading level grew very quickly initially. It’s time to let him develop the necessary maturity and experiences to interpret the more advanced conceptual content that is going to be outside his ability to understand. As a reader he will not be motivated if he is forced to work within his reading level. The available materials will be limited in number and those titles that are available will be overwhelmingly nonfiction. His rapid rise in reading levels should be rewarded with the authority to self-select content that appeals to him, even if it is only in the 4th-5th grade band because (we’ve already seen it) fiction is not well-represented in the higher reading levels.

This is my great concern: we’ve come to focus so heavily on using reading levels to assist those students who struggle with independent reading that we treat proficient readers in the same way as struggling readers, and so stifle their passion with our good intentions.

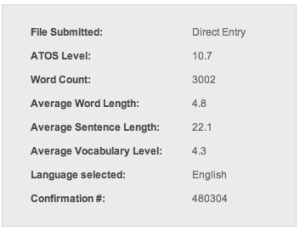

The preceding blog post has an ATOS of 10.7; here is the report for ATOS Level according to the ATOS Analyzer:

Resources:

“Common Core Common Core State Standards For English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Appendix A: Research Supporting Key Elements of the Standards.” Common Core State Standards Initiative, n.d. Web. 16 Jan. 2014. <http://www.corestandards.org/assets/Appendix_A.pdf>.

Milone, Michael, Phd. “The Development of ATOS.” Renaissance Learning, 2012. Web. 16 Jan. 2014. <http://doc.renlearn.com/KMNet/R004250827GJ11C4.pdf>.

“Text Complexity Grade Bands and Lexile Bands.” The Lexile Framework for Reading. MetaMetrics, Inc., n.d. Web. 17 Jan. 2014. <http://www.lexile.com/using-lexile/lexile-measures-and-the-ccssi/text-complexity-grade-bands-and-lexile-ranges/>.

“Using ATOS to Address Text Complexity.” Renaissance Learning. N.p., 2014. Web. 16 Jan. 2014. <http://www.renlearn.com/textcomplexity/usingatos.aspx>.