Wild England - After London, reading Richard Jefferies

The Story of my Heart , by nineteenth century author Richard Jefferies , is one of my most precious books, consumed first when I was a romantic girl and re-read several times since. Nothing and no-one else has ever been able to convey for me the ecstasy of being part of the natural world, that sense of being one with the universe, the way that Jefferies did in that book. It's almost pagan in its sentiments. But, oddly, although I've loved his nature writing, I've never read any of the fiction that Jefferies wrote.

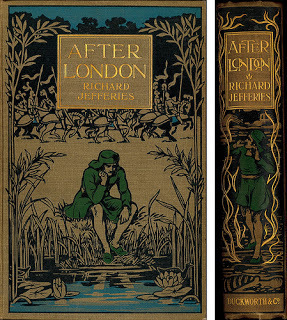

I came across '

After London, or Wild England

' through reading Philip Hoare, and now I can't believe I've not found it before. It's a dystopian view of the world, written in 1885, before dystopia was fashionable. Society has collapsed and the population of England has mysteriously vanished. Civilisation, as we know it, is now pre-history. The big cities have crumbled into ruin, overgrown by bramble and saplings, and London has disappeared under a vast inland lake. Previously domestic species have discovered their original instincts, alongside zoo animals and migrating animals. The few remaining human beings have also gone feral. England has gone wild.

I came across '

After London, or Wild England

' through reading Philip Hoare, and now I can't believe I've not found it before. It's a dystopian view of the world, written in 1885, before dystopia was fashionable. Society has collapsed and the population of England has mysteriously vanished. Civilisation, as we know it, is now pre-history. The big cities have crumbled into ruin, overgrown by bramble and saplings, and London has disappeared under a vast inland lake. Previously domestic species have discovered their original instincts, alongside zoo animals and migrating animals. The few remaining human beings have also gone feral. England has gone wild.'Footpaths were concealed by the second year, but roads could be traced, though as green as the sward, and were still the best for walking, because the tangled what and weeds, and, in the meadows, the long grass, caught the feet of those who tried to pass through. Year by year the original crops of wheat, barley, oats and beans asserted their presence by shooting up, but in gradually diminished force, as nettles and coarser plants such as the wild parsnips, spread out into the fields from the ditches and choked them.

Aquatic grasses from the furrows and water-carriers extended into the meadows, and, with the rushes, helped to destroy or take the place of the former sweet herbage. . . . Sapling ashes, oaks, sycamore, and horse-chestnuts, lifted their heads. Of old time the cattle would have eaten off the seed leaves with the grass so soon as they were out of the ground, but now most of them took root and grew into trees. By this time the brambles and briars had choked up and blocked the former roads, which were as impassable as the fields.

No fields, indeed, remained, for where the ground was dry, the thorns, briars, brambles and saplings filled the space and these thickets and the young trees had converted most part of the country into an immense forest. Where the ground was naturally moist, and the drains had become choked with willow roots, sedges and flags and rushes covered it. Thorn bushes were there, too, but not so tall; they were hung with lichen. Besides the flags and reeds, vast quantities of the tallest cow-parsnips rose five or six feet high and the willow herb with its stout stem, almost as woody as a shrub, filled every approach.

By the thirtieth year there was not one single open place, the hills only excepted, where a man could walk, unless he follow the tracks of wild creatures or cut himself a path.....'

After London

is a fictional history of the cataclysm and its aftermath, written by some future scribe. It's the long, novella length, prelude to a novel, which features some of the human beings now living in the new age of barbaric survival. This makes it a broken-backed kind of book and I didn't enjoy the novel in the same way that I enjoyed the first one. It's such a beautiful vision of England gone wild - a possible pre-vision of what the future might look like. Because it's out of copyright it can be

downloaded from the internet free

from the Gutenberg project.

After London

is a fictional history of the cataclysm and its aftermath, written by some future scribe. It's the long, novella length, prelude to a novel, which features some of the human beings now living in the new age of barbaric survival. This makes it a broken-backed kind of book and I didn't enjoy the novel in the same way that I enjoyed the first one. It's such a beautiful vision of England gone wild - a possible pre-vision of what the future might look like. Because it's out of copyright it can be

downloaded from the internet free

from the Gutenberg project.

Published on July 18, 2013 07:20

No comments have been added yet.