Remembering the Scientist Pope

“See those towers?” Costantino Sigismondi points to the two square Romanesque towers crowning Saint John Lateran. “We can imagine Gerbert up there looking at the stars.”

“See those towers?” Costantino Sigismondi points to the two square Romanesque towers crowning Saint John Lateran. “We can imagine Gerbert up there looking at the stars.”In 2008, while researching my biography of Gerbert of Aurillac, the French mathematician who became Pope Sylvester II, I visited Rome. I met my guide to the city, Costantino Sigismondi, through his website, where he had posted all of Gerbert’s known works. This year, on May 10, Sigismondi has organized a full day of lectures devoted to Pope Sylvester II at Rome’s Sapienza University. On May 12, a mass will celebrate the 1010th anniversary of Gerbert’s death. I wish I could join Sigismondi for the festivities. He's one of those rare people who brings light to the Dark Ages.

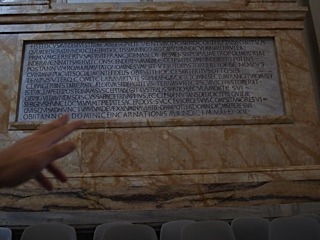

Sigismondi, an astrophysicist, teaches the history of astronomy at the University of Rome. In 2000, a friend reading Sky & Telescope chanced upon an article about “Y1K’s Science Guy,” Gerbert of Aurillac. She sent it to Sigismondi, who was astonished. Why hadn’t he known about The Scientist Pope? Sigismondi immediately contacted the Vatican and, with the pope’s support, began planning a series of lectures and events to commemorate the millennium of Gerbert’s pontificate (999-1003), including a grand requiem mass in the cathedral of Saint John Lateran in 2003.

Now we were in the square on the north side of the basilica; we turned to see an obelisk covered with hieroglyphics. “That wasn’t there when Gerbert was pope. We need to go to the Campo Marzio, close to the Pantheon. Ten years before Christ, Augustus put an obelisk there to make a sundial. One of the legends of Gerbert, you remember—William of Malmesbury tells it—is the story of Gerbert and a servant walking through the Campo Marzio, and Gerbert suddenly understands the Augustine obelisk. This is the story of the buried treasure.”

William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, describes not an obelisk but “a statue … pointing with the forefinger of the right hand, and on its head were the words ‘Strike here.’” It was all battered with blows from men who had done the obvious. Gerbert found “quite another answer to the riddle. At midday with the sun high overhead, he observed the spot reached by the shadow of the pointing finger, and marked it with a stake.” He returned at night with a servant and, presumably a shovel. They quickly found themselves in “a vast palace, gold walls, gold ceilings, everything gold; gold knights seemed to be passing the time with golden dice, and a king and queen, all of the precious metal, sitting at dinner with their meat before them and servants in attendance; the dishes of great weight and price.” The palace was magically lit by a sparkling jewel; a golden boy stood opposite it, “holding a bow at full stretch with an arrow at the ready.” Gerbert’s servant, overcome with greed, snatched a golden knife. At once the figures came alive with a roar. The boy loosed his arrow and put out the light. And “had not the servant, at a warning word from his master, instantly thrown back the knife, they would both have paid a grievous penalty.” They covered their tracks and said no more about it.

William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, describes not an obelisk but “a statue … pointing with the forefinger of the right hand, and on its head were the words ‘Strike here.’” It was all battered with blows from men who had done the obvious. Gerbert found “quite another answer to the riddle. At midday with the sun high overhead, he observed the spot reached by the shadow of the pointing finger, and marked it with a stake.” He returned at night with a servant and, presumably a shovel. They quickly found themselves in “a vast palace, gold walls, gold ceilings, everything gold; gold knights seemed to be passing the time with golden dice, and a king and queen, all of the precious metal, sitting at dinner with their meat before them and servants in attendance; the dishes of great weight and price.” The palace was magically lit by a sparkling jewel; a golden boy stood opposite it, “holding a bow at full stretch with an arrow at the ready.” Gerbert’s servant, overcome with greed, snatched a golden knife. At once the figures came alive with a roar. The boy loosed his arrow and put out the light. And “had not the servant, at a warning word from his master, instantly thrown back the knife, they would both have paid a grievous penalty.” They covered their tracks and said no more about it.If this story were set in Reims, I could pooh-pooh it as utter fantasy. But Rome? In 2005, archaeologists were using a coring drill to survey the foundations of Caesar Augustus’s palace on the Palatine Hill. Fifty feet down, the drill plunged into a void. Sending down a camera, the crew discovered a sacred grotto—a round, domed room about twenty-five feet high and twenty-five feet across, covered with mosaics of marble and seashell. In the soft light of the remote-sensing probe, they glittered like gold.

Whether or not Gerbert found buried treasure, if he understood how an obelisk worked as a sundial, he would have understood the Clementine Sundial in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Sigismondi had demonstrated it to me that noon. The church is an architectural pastiche, the interior by Michelango, the exterior a ruined Roman bath. The meridian line of the sundial is not squared with the church—it was added later, the church being chosen for the purpose because of its stable Roman walls and suitable dimensions. The pinhole that lets in the sunlight was set into a great bronze sculpture of the arms of Pope Clement XI (1700-1721) that cuts into one of Michelangelo’s ornate arches. New marble mosaics were set into the floor to create the zodiac images that flank the line, which is made of brass.

Whether or not Gerbert found buried treasure, if he understood how an obelisk worked as a sundial, he would have understood the Clementine Sundial in the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Sigismondi had demonstrated it to me that noon. The church is an architectural pastiche, the interior by Michelango, the exterior a ruined Roman bath. The meridian line of the sundial is not squared with the church—it was added later, the church being chosen for the purpose because of its stable Roman walls and suitable dimensions. The pinhole that lets in the sunlight was set into a great bronze sculpture of the arms of Pope Clement XI (1700-1721) that cuts into one of Michelangelo’s ornate arches. New marble mosaics were set into the floor to create the zodiac images that flank the line, which is made of brass.“The meridian occurs in this line,” Sigismondi said, putting a blank sheet of white paper near the line so that the faint sun on this cloudy day was more visible. “It’s different for every day. It goes to 12:24 in February, comes back to 12:20 now in March. And back to 12 in October. This is the so-called equation of time. If you take this and put it to local noon time, noon”—when the image of the sun crosses the line—“equals halfway between dawn and sunset.

“If mass is at noon,” he added, “sometimes the transit will happen during mass. If mass is at 12:30, then the faithful can attend mass, the astronomer can do his work, and the faithful astronomer can do both. The priests here are very open. They moved the mass to 12:30 for this reason.” And every day that he works in the cathedral, Sigismondi also takes part in the 12:30 mass, volunteering to read the scripture and take the offerings.

“If mass is at noon,” he added, “sometimes the transit will happen during mass. If mass is at 12:30, then the faithful can attend mass, the astronomer can do his work, and the faithful astronomer can do both. The priests here are very open. They moved the mass to 12:30 for this reason.” And every day that he works in the cathedral, Sigismondi also takes part in the 12:30 mass, volunteering to read the scripture and take the offerings.“I am practically the resident astronomer of Santa Maria degli Angeli,” he said. He has held conferences and astronomy classes in the church; on a side table, surrounded by sacred literature for sale, is a one-euro pamphlet he wrote called “Astronomy in the Church.” The pamphlet gives his email address if anyone would like further information on this partnership between religion and science.

Sigismondi has also used the sundial for original scientific research. “I measure this meridian line with video cameras to take scientific information as accurate as possible. Looking at the sun, it is possible to measure all the parameters of the solar orbit with a precision difficult to achieve with a normal telescope. You can measure the angles of the sun with greater precision because there is no lens—there is no border effect. The border effect of a lens is remarkable. The pinhole, on the other hand, is aberrationless. The only abberation is due to the atmosphere.

“What’s the link between this meridian line and our Gerbert? There’s no real link, because this line was built seven centuries later.

“But it was built by a pope, by a successor of his, Clement XI. He became pope on November 23, 1700. By the first of January, the astronomers were already building this line for him. Only seventy years after the Galileo affair, the pope was building this scientific instrument in the church—and this instrument can distinguish between the Copernican system, with the earth going around the sun, and the Ptolemaic system, with the sun going around the earth. With this instrument of the pope’s, you can prove that the earth goes around the sun.

“But it was built by a pope, by a successor of his, Clement XI. He became pope on November 23, 1700. By the first of January, the astronomers were already building this line for him. Only seventy years after the Galileo affair, the pope was building this scientific instrument in the church—and this instrument can distinguish between the Copernican system, with the earth going around the sun, and the Ptolemaic system, with the sun going around the earth. With this instrument of the pope’s, you can prove that the earth goes around the sun.“And this was possible in Gerbert’s time. If you use only the duration of the seasons, then Ptolemy works. If you can see the image of the sun—as you can with this sundial—then Ptolemy fails.”

Sigismondi speculates that this kind of sundial was the sensational object that Gerbert made for Otto III in Magdeburg—what Thietmar of Merseburg called an horologium, a “time-keeper,” translated variously as an astrolabe, a nocturlabe, a clepsydra, a celestial sphere, or a sundial. “This kind of clock is very easily made by someone like Gerbert,” Sigismondi said, “someone brilliant who understood the idea of using a tube to observe the stars, someone who could make his spheres. A sighting tube is not so different from the type of camera obscura you have here. The function of the church is just to make a dark space so that the light coming through the pinhole can be seen.

“We can’t say that this is what Gerbert made at Magdeburg, but there is room to dream in the history of science. We can’t say he didn’t. And it’s something he could have done. It’s plausible. Gerbert was about four hundred years ahead of the contemporary people, scientists and scholars included. Many of them understood that he was really outstanding. He was very respected as pope. I would like to see him sainted, or at least blessed. Abbo was sainted, and Gerbert was better than Abbo.”

If anyone could do it, Sigismondi could. A self-proclaimed “faithful astronomer,” he is equally at home in his astrophysics laboratory and in the Vatican; his university website features a photo of him kneeling before the pope. An eager teacher, he had led me on an enthusiastic all-day tour of Rome, highlighting the priest who was carving a new sun to reconstruct a medieval armillary sphere much like the one Gerbert had made; the Jesuit who had originated the field of astrophysics; the pope who had studied the dimensions of the sun.

If anyone could do it, Sigismondi could. A self-proclaimed “faithful astronomer,” he is equally at home in his astrophysics laboratory and in the Vatican; his university website features a photo of him kneeling before the pope. An eager teacher, he had led me on an enthusiastic all-day tour of Rome, highlighting the priest who was carving a new sun to reconstruct a medieval armillary sphere much like the one Gerbert had made; the Jesuit who had originated the field of astrophysics; the pope who had studied the dimensions of the sun.The more time I spent with him, the more he seemed like Gerbert himself—Equally in leisure and in work we both teach what we know, and learn what we do not know. Or, perhaps like Gerbert’s beloved friend, the sweet solace of his labor, a man with the same first name: Costantino Sigismondi was Gerbert’s twenty-first century Constantine, who would keep the story of The Scientist Pope alive.

Join me again next Wednesday at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com for another writing adventure in Iceland or the medieval world.

Published on May 08, 2013 03:31

No comments have been added yet.