Sur la Teche: Exploring the Bayou by Canoe, Stage 3

Note to reader: This is still a draft. . . .

Continued from Part II:

The third leg of our Teche trip took place on December 3, 2011, and stretched between the towns of Parks and Loreauville. The temperature that day was 55 °F in the morning, 81 °F in the afternoon; the sky was partly cloudy. Present, as always, were Keith Guidry and myself. On this particular stage, however, we were accompanied by biologist Don Arceneaux, who shared our interest in the bayou and its remarkable history. Don would follow us in his small one-man kayak.

We put in at 9 a.m. at Cecile Rousseau Memorial Park in Parks. Passing many modern houses along the Teche, we soon reached the community of St. John, the first sugar plantation we encountered since starting our trip at Port Barre months earlier. As The Louisiana Planter and Sugar Manufacturer noted in 1890:

St John sugar refinery’s almost new outfit will meet a splendid and very large sugar crop this grinding [season] in St Martin parish. This excellent central sugar system by its benign influence . . . has encouraged for many miles around the growth of sugar cane. Col. J. B. Levert, the enterprising owner of the large sugar estate St John and its grand sugar refinery, deserves credit for his push and energy and public spirit.

Approaching the St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.

Approaching the St. John sugar refinery near St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

St. John Plantation, now organized under the modern corporate name Levert-St. John, LLC, is owned by the Levert Companies. As the company’s website notes, “The principal asset of this company [Levert-St. John] is agricultural land (approximately 11,000 total acres), all in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana. The Levert-St. John, LLC lands are made up primarily of four plantations, St. John, Banker, Burton and Stella, all in St. Martin Parish.” Of that 11,000 acres, approximately 75% concerns sugar production, the remainder focusing primarily on rice and crawfish production.

St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.

St. John sugar refinery on Bayou Teche.(Photo by author)

The sugar refinery at St. John dominates the surrounding landscape of flat sugarcane fields. We were fortunate to canoe past the structure at the height of grinding season (which runs from October to January), when the complex belches enormous clouds of steam into the winter sky. At any given time sugar mills either smell pleasantly sweet, like molasses, or they emit a god-awful stench, to which nothing of a polite nature compares. St. John must have smelled sweet that day, because I made no reference to the odor in my journal, and I think I would have remembered the alternative.

In addition to the hissing, breathing refinery, canoers will see here the 264-foot-long, 14.7-foot-wide Levert-St. John Bridge, which appears on the National Register of Historic Places (site #98000268, added 1998). A double Warren truss swing bridge made of rusted steel girders, it was constructed in 1895 for railroad and pedestrian traffic. Eventually, however, the rails were covered with asphalt to form a single-lane bridge for automobiles (which I remember driving across in the 1980s — not the most secure experience). According to a study conducted for its National Register candidacy, the Levert-St. John Bridge is “the oldest known [extant] bridge in Louisiana, as well as the only known bridge of its type in the state. . . .”

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.

The now defunct Levert-St. John Bridge.Note the year "1895" is cut into the steel plate above the entrance.

(Click to enlarge; photo by author)

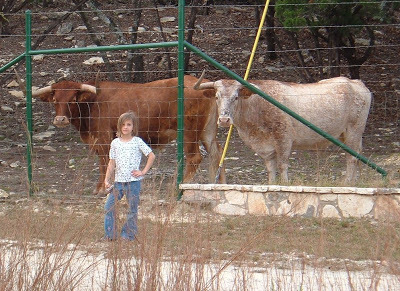

After paddling around and even under the bridge, Keith, Don, and I continued on toward St. Martinville. On the outskirts of town we reached the Longfellow-Evangeline State Historic Site (more on Longfellow and Evangeline below), the centerpiece of which is Maison Olivier, a “Raised Creole Cottage . . . which shows a mixture of Creole, Caribbean, and French influences.” The home was built circa 1815 by French Creole planter Pierre Olivier Duclozel de Vezin (from whom two of my canoeing partners, Preston and Ben Guidry, trace direct lineage through their maternal line). Unfortunately, I could not see the cottage from the bayou, but I did see Spanish longhorn cattle — a fitting living history display, because Spanish longhorn was indeed the variety of cattle raised in Louisiana during its colonial period (1699-1803). This variety is no longer seen in south Louisiana — at least not from my experience — although Texas longhorns still inhabit parts of that state, I having seen them for myself in the Hill Country.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.

My daughter flanked by two longhorns in Texas.(Photo by author)

Immediately south of Longfellow-Evangeline, and just beside St. Martin Senior High School (from which, by the way, Preston and Ben graduated), one can see, behind a low dam, the Cypress Bayou Coulee Canal running northwest into Bayou Tortue Swamp. A major wetlands area, Bayou Tortue Swamp begins on the north near Breaux Bridge and stretches to the Terrace Highway (Highway 96) on the south, and from the natural Teche levee on the east to an area abutting the Lafayette Regional Airport on the west. (It’s funny how I grew up in Lafayette never knowing such a large swamp existed nearby. Granted, I knew Lake Martin, but I had no idea it was part of a much larger swamp ecosystem.)

The cement boat at St. Martinville.

The cement boat at St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

As we neared downtown St. Martinville, Keith showed me two landmarks that Preston had mentioned to me earlier. One of these landmarks is a boat made out of cement, now dilapidated and slowly sinking into the bayou. Cement boats, it turns out, are not unheard of. The other landmark is the site of a small cave in which local children used to play. Infinitely smaller than the one in which Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher became lost, the cave entrance has now been sealed with cement for reasons of safety; but you can see the cement patch over the cave’s entrance, about a hundred yards from the downtown bridge over the Teche. Preston once shoved a paddle into a crack in the cement, and the paddle went in all the way to the grip — a good five feet or so. (I once explored a similar cave in a bluff of the Vermilion River, just south of the bridge over which E. Broussard Road [Highway 733] crosses that bayou. There was not much to the cave: its light-colored dirt or clay walls extended into the bluff about ten or twelve feet before ending in a small hole in the ceiling, which in turn opened onto a pasture.)

Cement now covers the cave entrance.

Cement now covers the cave entrance.(Photo by author)

From the bayou at St. Martinville we saw St. Martin de Tours Catholic Church, the Acadian Memorial, the Museum of the Acadian Memorial, the adjacent African-American Museum, the Old Castillo Hotel (about which I’ve written previously) and the Evangeline Oak, under which the Acadian maiden Evangeline went insane pining for her lost love Gabriel . . . well, that is how I heard the story. American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow mentions St. Martinville in his epic poem Evangeline, first published in 1847:

On the banks of the Têche, are the towns of St. Maur and St. Martin. There the long-wandering bride shall be given again to her bridegroom, There the long-absent pastor regain his flock and his sheepfold.

In his book In Search of Evangeline, historian Carl A. Brasseaux has demonstrated that Evangeline never existed; nor did Emmeline Labiche, an Acadian exile on whom Longfellow supposedly based the character of Evangeline. Thus, neither Evangeline nor Emmeline are buried under “Evangeline’s Tomb” in St. Martinville. Yet the events against which Longfellow set the tragedy of Evangeline — the brutal mid-eighteenth-century expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia by the British military — is factual, as is the eventual settlement of many Acadian exiles in the St. Martinville area (among them my own ancestors, including Michel Bernard, husband of Marie Guilbeau, who arrived in 1765 with Beausoleil Broussard).

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.

"Evangeline's Tomb," St. Martinville, Louisiana.(Photo by author)

According to various sources, St. Martinville was known in olden times as “le petit Paris” because of its lavish social life — a story I’ve always regarded with some skepticism. Occupied since the mid-1700s, the place amounted to little more than a neglected military outpost, the Poste des Attakapas, until the early nineteenth century, when local landowners divided their property into lots; sold or rented these parcels to settlers; and called the resulting community “St. Martinsville,” after the local church’s patron saint. Thus, there seems to have been little time for St. Martinville to have flourished as a “little Paris” before the onslaught of tough economic times during and after the Civil War. The “petit Paris” claim, however, can be traced back as far as 1884, when (oddly enough) The Irish Monthly magazine of Dublin reported, “Before the war, which was peculiarly disastrous in its effects on this town, St. Martin’s used to be called Le petit Paris and was perhaps the most aristocratic place in Louisiana. But now many of its houses look old and dilapidated, and few traces of the little Paris remain.” (Source: Anonymous, “From Acadie to Attakapas: The Wanderings of Evangeline,” The Irish Monthly 12 [1884], p. 179.)

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).

Cover of Brasseaux's French, Cajun, Creole, Houma (2005).Brasseaux shares my skepticism, however, observing,

The Creoles’ fall from grace [after the economic devastation of the Civil War] gave rise to a body of mythology regarding a golden age that never was. Most southern Louisianians are familiar with the stories of the spiders imported from China for the Oak and Pine Alley wedding [held near St. Martinville], with the celebrated performances of French opera companies in antebellum St. Martinville, with the presence of the great houses of French nobility who took refuge along Bayou Teche after the French Revolution, and with the donation of a baptismal font by Louis XVI to St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church — all stories proven unfounded by recent historical research. Yet these stories persist because they gave, and still provide, the fallen Creole elite with a continuing sense of social prominence based upon perceived past glories. (Brasseaux, French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana [2005], p. 102.)As we left St. Martinville and paddled into the countryside, I spotted a few ibises on a mud flat, pecking away at minnows. As a historian I found this of interest because the ibis, with its distinctive downturned beak, is strongly linked to ancient Egypt. There religious mythology associated the ibis with Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing. The “father of history,” Herodotus, recorded of ancient Egypt, “When a man has killed one of the sacred animals, if he did it with malice . . . he is punished with death; if unwittingly, he has to pay such a fine as the priests choose to impose. When an ibis, however, or a hawk is killed, whether it was done by accident or on purpose, the man must needs die [my italics].” The ibises we saw that day were young white ibises whose plumage had not yet turned completely white.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.

A pair of ibises along the Teche below St. Martinville.(Photo by author)

A little after 1 p.m. we spotted the Keystone Lock and Dam, for all practical purposes a convenient line of demarcation between the upper and lower Teche. Between the dam and us floated numerous islands of water hyacinth, one of them, the largest, measuring about 75 feet in length. Since starting our trip at Port Barre, we have worried about hyacinth. An invasive species, we feared it would at some point block our progress, clogging the entire bayou from one bank to the other. Those we now saw represented the largest concentration we had yet encountered, but it was not enough to stop us; we merely paddled around the aquatic plants or sometimes plowed straight through them, feeling the drag on the bottom of the canoe. Aerial photographs showed even denser masses of water hyacinth ahead of us, near Baldwin and Franklin. But we would not reach those towns on the current stage.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.

A raft of water hyacinths floating on the Teche.The Keystone Lock and Dam are in the distance.

(Photo by author)

As we closed in on the dam, the sound of water topping the cement structure became louder. Here we had no choice but to do a portage. I don’t know how people pronounce “portage” elsewhere in the country, but in south Louisiana the most common pronunciation I hear is the French pronunciation, which is POR-TAHZH. What is perplexing, however, is that the French place name Fausse Pointe — an archaic name for our stopping point that day, Loreauville, as well as for a stretch of the Teche near New Iberia, and now the name of a nearby lake and state park — is almost universally pronounced, even by Cajuns who know the local patois, in the Anglo manner — that is, FAW-SEE POINT instead of the traditional FAHS POINT. This pronunciation jars me, just as the Anglo pronunciation of portage jars me.

We went ashore here to make a portage.

We went ashore here to make a portage.(Photo by author)

So we made a portage, hauling our canoe and Don’s kayak up a steep embankment on the east side of the Teche, carrying the boats about a hundred yards along a trail through some woods, lowering them down another embankment (much steeper than the first), and putting them back into the water just below the lock and dam. The Tour du Teche race organizers had sunk some 4x4 posts in this last embankment and, evidently running ropes along the posts, had rigged up a method for lowering canoes into the bayou. Unfortunately, no ropes were present on our visit, so we had to make do without this convenience. (Were we trespassing here? It was unclear: We exited the bayou on federal property, but at some point may have entered private property. I say this because just before we lowered our canoes back into the water we spotted a “Private Property” sign — but, confusingly, it was facing the wrong direction, so that canoers could not see the sign until after the fact. In any event, canoers cannot pass the dam and lock without making a portage, and as a result the location offers itself as a legitimate candidate for right of way. But I leave this matter for others to solve.)

Keystone Lock and Dam from downstream.

Keystone Lock and Dam from downstream.(Photo by author)

Once back in the water, we continued to paddle downstream, noting juglines on the bayou and beaver gnaw mark on the tree trunks. We passed the entrance to the Joe Daigre Canal, which runs a short distance to Bayou Tortue. In turn, that bayou wraps itself around the northern bank of Spanish Lake before running into Bayou Tortue Swamp.

Don Arceneaux in his kayak.

Don Arceneaux in his kayak.(Photo by author)

At 2:50 p.m. we reached Daspit Bridge, and it was around this time that we noticed a sweet molasses smell — another sugar refinery in operation. We passed many modern suburban houses on the east bank and at 3:20 p.m. I spotted a wall of green in front of us — What was it? I wondered. A painted green wall, perhaps the side of a large barn? It seemed to rise two stories or more. I eventually realized it was a grassy hill rising above the bluffs along the bayou. “What is this place?” I asked Don, who, it turned out, knew precisely what it was. He’d scouted ahead, putting his kayak in near Daspit Bridge a few days earlier. Now he was toying with me, awaiting my reaction to the grassy hill, below which a coulee or small bayou entered the Teche.

It was the mouth to Bayou La Chute and the site of the eighteenth-century waterfall that emptied into the Teche.

Entrance to Bayou La Chute (center) as seen from the Teche.

Entrance to Bayou La Chute (center) as seen from the Teche.The grassy hill is at right, appearing lower here than from a distance.

(Photo by author)

Don had identified this site as the probable location of the waterfall — it just made sense, topographically. Additional research on my part, however, revealed that locals called this small tributary Bayou La Chute . . . and “La Chute” in French means “the waterfall.” (See my detailed article on our search for the waterfall’s site.) There is no waterfall today, its ten-foot drop, made of dirt or clay, having eroded away, or been removed by human activity.

A paddle up Bayou La Chute is worth the effort. Although modern neighborhoods encroach on more than one side (including a neighborhood under construction), I found Bayou La Chute in some ways more beautiful than the Teche. In its dark swampiness I half expected to see Yoda, and because of its winding narrowness, lined with bamboo (a nonindigenous plant no doubt loosed from someone’s garden), it reminded me of an amusement park jungle ride.

On Bayou La Chute; for scale, note fishing chair on left bank.

On Bayou La Chute; for scale, note fishing chair on left bank.(Photo by author)

We stopped at a fork in Bayou La Chute, and made our way back to the Teche to continue toward Loreauville. With the sun sinking and the sky dimming, we had one more discovery to make that day, the so-called “tombs” I mentioned inone of my previous articles. I no longer think these are tombs, but, rather, pilings belonging to a nineteenth-century sugar mill or steam pump. Indeed, we were now in sugar country, passing through one former sugar plantation after another — some now transformed into neighborhoods, some still producing sugar, but, of course, without the slaves who once carried out the grueling tasks associated with making sugar —cutting cane by hand, hauling it to the sugar house, feeding it into the rollers, boiling the saccharine juice, refining it again and again until, at the exact moment, a “strike” is poured, and if all went well creating granulated brown sugar seeped with molasses. Loaded into oversized barrels called hogsheads, the commodity traveled via Teche steamboat to New Orleans, where it would be sold on the market, or transferred to schooner for sale in the markets of the East Coast.

"Tombs" on the Teche.

"Tombs" on the Teche.I now believe these are old industrial pilings.

(Photo by author)

On the outskirts of Loreauville we saw three immense boat-building facilities and a couple of vessels associated with the petroleum industry — a living quarters boat and a jack-up boat. These sites reminded us that although we paddled inland on a bayou whose mouth did not even empty into open water (the Teche originally poured into the Lower Atchafalaya River, but now diverts into the Calumet Cut, known less poetically as the Wax Lake Outlet), we were nonetheless not that far from the Gulf of Mexico.

A typical scene on the Teche that day.

A typical scene on the Teche that day.(Photo by author)

Modern homes and businesses ran along the bayou at Loreauville. We drew up to our pre-designated landing, at the town’s bridge, which stands next to a volunteer fire station and the old town jail from, I presume, the early twentieth century. We debarked and hauled the canoe and kayak up a high bluff below the jailhouse. Don had an easier time with his small kayak, but Keith and I struggled with the 17-foot metal canoe. Wrestling with the boat, the two of us suffered simultaneous asthma attacks — in retrospect a humorous turn, though not at the time. Fortunately, we each brought an inhaler, and soon were enjoying hamburgers at the nearby (and aptly named) Teche Inn, located in Loreauville a short walk from the bayou.

Published on November 25, 2012 17:11

No comments have been added yet.