Ctesiphon - Fallen City of the Sassanid Kings - Part One

Beside the River Tigris stand the remains of the royal capital of not just one but two great ruling dynasties of the ancient world. The remains of the city of Ctesiphon today lie some 20 miles from Baghdad and have seen better days.

Ctesiphon began life as a small and unimposing cluster of dwellings across the river from the city of Seleucia-on-the-Tigris, capital of the Hellenistic Kings who at the height of their powers had ruled over a sprawling inheritance stretching from the shores of the Aegean to the Hindu Kush. These lands, hard-won by Alexander and bitterly contested by his successors had eventually come into the possession of Seleucus, the onetime commander of one of Alexander’s elite regiments and political survivor par excellence.

The descendants of Seleucus had ruled over their empire as the Greek speaking successors to the almighty kings of Persia that their illustrious ancestor had had a hand in overthrowing, with all the attendant pomp and bluster, until one day King Antiochus IV was humbled by a Roman Pro-Consul who took his sword and drew a line in the sand around the king and dared him to step over it. It was an eloquent illustration of the decay of the Seleucid Dynasty in the face of the inexorable rise of Rome, which had already deprived them of some of their wealthiest territories. By the time that Pompey the Great made his triumphant progress through the former Seleucid territories of the Near East, annexing a province here, setting up a petty client kingdom there, the Seleucid monarchs were no more; their line extinguished in fratricidal mayhem. It was not the Romans who had done for the Seleucids however, neither was it King Tigranes the Great of Armenia, whom Pompey had lately overthrown to take possession of a swath of formerly Seleucid territory that the Armenian ruler had made his own. Instead it was a formerly subject people of the Seleucid Kings who had struck the most decisive blow. The Parthians, a rough around the edges, formerly nomadic people who had occupied the north-eastern fringes of the Seleucid Empire and had paid little more than grudging lip service to the kings ruling in Seleucia, had risen against their nominal masters. Over the course of a century from attaining effective independence, the Parthians had grown from a nuisance to a dangerous rival to a deadly threat. In 139 BC, following a disastrous punitive expedition by the Seleucid King Demetrius II, the Parthian King Mithridates had taken Demetrius prisoner and held him captive for ten years. In 126 BC the Parthians advanced upon and took control of Seleucia. Rather than making it their own however, they left it as an entrepot of Greek merchants who lived under the protection of the new Parthian rulers and instead set up their capital across the river in Ctesiphon.

In 53 BC at the Battle of Carrhae, the formidable horse archers and cataphracts of Parthia had destroyed a Roman army under Marcus Crassus, inflicting on the Republic one of the worst defeats in its history. From this point Rome knew no deadlier rival and a grudging respect grew up between the two great empires that faced each other across the Euphrates.

The Parthian rulers however found themselves faced in the end with the same problems as their Seleucid predecessors; a vast and sprawling territory to control, fiercely independent subjects whose loyalty could never be taken for granted and a large and aggressive neighbour which would take advantage of any sign of weakness.

In 116 AD Rome’s greatest soldier-emperor Trajan did just this, advancing deep into Parthian territory and capturing Ctesiphon. Although stiffening resistance and trouble in Egypt forced Trajan to withdraw, he did so having stripped the Parthian capital of enormous wealth, much of it generated through a stranglehold on the silk trade which passed through Parthian territory.

By the time of the final, fatal revolt against Parthian rule in 226 AD, the Romans had repeated this feat twice more, each time withdrawing with vast quantities of loot. The credibility of the Parthian ruling house was in tatters. The revolt was led by Ardashir, a petty king who had laid claim to the ancient titles of Persian kingship and who now marched against the last Parthian ruler Artabanus IV, defeating him in battle and laying claim to all of his territories to usher in an era of a second great Persian Empire; that of the Sassanids. Ardashir rejected Ctesiphon with its Parthian associations and instead began redeveloping Seleucia as his seat of power; renaming it Veh Ardashir. The ever fickle Tigris had other ideas however, shifting its course to bring destruction to the new king’s efforts.

Under Ardashir’s son Shapur, Persia would prove once more to be a formidable opponent of Rome. His forces probed the Roman defenses and at times advanced deep into imperial territory, capturing strategic cities and inflicting stinging defeats on the forces of emperors Alexander Severus and Gordian III. His efforts culminated in the capture and sack of Antioch. In 260 AD Shapur would take prisoner and subsequently enslave the Roman emperor Valerian. Roman pride had never known a more terrible shame.

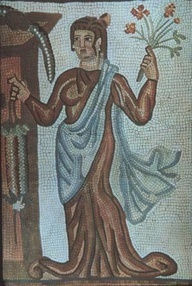

Shapur constructed himself a splendid new palace at Ctesiphon fit for a King of Kings. Little if anything remains of this structure. Some surviving mosaics from Shapur’s better preserved palace at Bishapur (below) however give an indication of the rich decoration that the palace would doubtless have featured.

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Architecture/ayvan_e_khosrow.htm

http://www.islamic-architecture.info/WA-IQ/WA-IQ-019.htm

Published on October 29, 2012 18:19

No comments have been added yet.

Slings and arrows

Nuggets of history from the author of 'The Battles are the Best Bits'.

Nuggets of history from the author of 'The Battles are the Best Bits'.

...more

- Simon B. Jones's profile

- 22 followers