Science Friction

Contrary to the common misconception perpetuated on Amazon, science fiction is not in any way related to fantasy.

Contrary to the common misconception perpetuated on Amazon, science fiction is not in any way related to fantasy.

True science fiction is the hypothetical conjecture of how science could, in one form or another, shape the world of the future, and in that regard it is forward thinking.

Science fiction looks to preempt and predict how mankind will adapt to the challenges of the future.

Science fiction classics could loosely be termed science friction in that they agitate and challenge preconceptions. Throughout its brief history, the best loved science fiction stories have been those that dared to challenge the status quo.

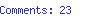

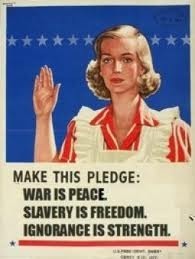

George Orwell’s 1984 is, arguably, the greatest science fiction novel ever written.

Half a century before Skype video chats and Google hangouts, George Orwell saw the danger of our seemingly innocuous video screens with their built-in cameras.

Half a century before Skype video chats and Google hangouts, George Orwell saw the danger of our seemingly innocuous video screens with their built-in cameras.

Thought-police, newspeak and Big Brother became the clarion called that allowed the West to avoid the Stalinist-style abuse of technology portrayed in 1984.

If you’ve read Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago you’ll understand this was no idle, misplaced phobia on Orwell’s part. Had Stalin, Hitler or Mao had access to such instruments of surveillance, their repressive, murderous regimes might still be with us.

And yet, a book review in 1949 noted “This may mean that [1984's] greatness is only immediate, its power for us alone, now, in this generation, this decade, this year, that [1984] is doomed to be the pawn of time. Nevertheless it is probable that no other work of this generation has made us desire freedom more earnestly or loathe tyranny with such fulness.” Far from being limited to its day, 1984 stands as a dire warning about the dangers of authoritarian rule for countless generations to come.

Slaughterhouse-Five is a reactionary tale, written by Kurt Vonnegut, capturing the trauma and senseless waste of war as he experienced it during the Allied fire bombing of Dresden.

Slaughterhouse-Five is a reactionary tale, written by Kurt Vonnegut, capturing the trauma and senseless waste of war as he experienced it during the Allied fire bombing of Dresden.

The book is fictional, but it is also allegorical and biographical, capturing the heartrending futility of death and violence as epitomized by destruction of Dresden. It’s hard to do the history of Dresden justice, needless to say, it was an Allied war crime. This excerpt from a survivor of the bombing conveys the horror Vonnegut witnessed.

Explosion after explosion. It was beyond belief, worse than the blackest nightmare. So many people were horribly burnt and injured. It became more and more difficult to breathe. It was dark and all of us tried to leave this cellar with inconceivable panic. Dead and dying people were trampled upon…

~

We saw the burning street, the falling ruins and the terrible firestorm. My mother covered us with wet blankets and coats she found in a water tub.

~

We saw terrible things: cremated adults shrunk to the size of small children, pieces of arms and legs, dead people, whole families burnt to death, burning people ran to and fro, burnt coaches filled with civilian refugees, dead rescuers and soldiers… and fire everywhere, everywhere fire, and all the time the hot wind of the firestorm [sucked] people back into the burning houses they were trying to escape from.

~

As a writer, Vonnegut could not ignore the devastation he’d witness in World War II. His protagonist is propelled around in time, chaotically flashing back and forth, capturing the emotional trauma of survivors in an allegorical fashion.

As a writer, Vonnegut could not ignore the devastation he’d witness in World War II. His protagonist is propelled around in time, chaotically flashing back and forth, capturing the emotional trauma of survivors in an allegorical fashion.

In Slaughterhouse-Five he wrote, “It is, in the imagination of combat’s fans, the divinely listless loveplay that follows the orgasm of victory. It is called ‘mopping up.’” In this way, Vonnegut sought to arrest our attention, to ensure the past was not buried and forgotten, to make sure that the lessons were learned, not ignored.

In the words of George Santayana, “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” Vonnegut was determined we should not forget.

Science friction is fiction that wakes us from our lethargy, stirring us to action.

Robert Heinlein wrote several stories in this category. But his classic, Starship Troopers, became a cautionary tale in a way Heinlein never intended.

In Starship Troopers, Heinlein sets out his arguments against communism, the Cold War, and the need for duty to reinforce responsibility, all set against the backdrop of an interstellar conflict with alien bugs.

Somewhat ironically, the extremist right-wing views he promoted as future social values backfired. Throughout the book his characters debate the weakness of democracy and the need for military service, but the book was published just a few years before the Vietnam war escalated out of control. Starship Troopers became a parody of reality.

Somewhat ironically, the extremist right-wing views he promoted as future social values backfired. Throughout the book his characters debate the weakness of democracy and the need for military service, but the book was published just a few years before the Vietnam war escalated out of control. Starship Troopers became a parody of reality.

The book’s description of society happily accepting life on a war footing became a stark contrast to the socially traumatic events of the 60s. If anything, Heinlein’s vision highlights a fascist extreme the US narrowly avoided.

In 1962, Heinlein wrote Stranger in a Strange Land. With its focus on the formation of a new religion comprised of celebrities, one wonders if he intended his “all worlds religion” as a mockery of scientology.

In stark contrast to Starship Troopers, Heinlein unveils a world of free love, drugs and promiscuity. With themes such as homosexuality, hippies and a fascination with psychic powers, the book preempted the radical movements of the 60s and 70s.

The US Congressional Library named Stranger in a Strange Land as one of a hundred books that helped shape modern America. The stark contrast between Starship Troopers and Stranger in a Strange Land captures the contradiction that was America in the 1960s.

Perhaps the most radical work of science fiction friction is Planet of the Apes.

Although the motivation for the book was originally to highlight cruelty to animals and to challenge the presumption of man’s position at the head of creation, the movie version became a social statement on US racial tensions.

The racial overtones are overt, and clearly not intended just as an analogy for animal cruelty. African-American slavery, segregation and discrimination are subject to a role reversal within the movie, with Charlton Heston appearing very much as a white European slave held in chains. This switch was intended to shock audiences into the realization that racism is unjust.

The racial overtones are overt, and clearly not intended just as an analogy for animal cruelty. African-American slavery, segregation and discrimination are subject to a role reversal within the movie, with Charlton Heston appearing very much as a white European slave held in chains. This switch was intended to shock audiences into the realization that racism is unjust.

White supremacists didn’t miss the point. In supremacist rallies in the late 60s, bigots displayed racist placards decrying what they saw as “Planet of the Apes” resulting from the dissolution of segregation.

In much the same manner, during some of the later movies in the series, black audiences cheered for Caesar, drowning out the movie’s dialogue as they cheered for his rebellion against oppression.

The point of all this is simple: We need mirrors.

We need to see ourselves in a mirror, to see who we are and where we are going in life, and science fiction does that, but not with flashy light-sabres and green muppets. Science fiction shows like Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica are legendary not because they fire photon torpedoes or travel faster than light, they preempted social change. It’s no surprise the first interracial kiss on TV occurred in Star Trek.

Science fiction can easily address topics we would not otherwise talk about. Often, these are the topics we needed to be talking about.

In the words of Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone, “I knew I could get away with Martians saying things Republicans and Democrats couldn’t.“

Science fiction should cause friction, but not to be obnoxious or sensational, to provoke critical thinking.