Extremophilephile: loving the unlovable

Extremophile describes organisms that “love” extremes, thriving in environments that would kill most cellular life. Extremophiles are so varied it’s hard to do this category of life justice in a blog post, so here’s just a sprinkling of some of those that catch my eye.

Life is… well, what adjective could accurately describe the versatility and diversity of life on Earth? Remarkable? Astounding? Incredible? Each of these superlatives pales in comparison to the wonder that is biology.

Life never ceases to surprise.

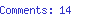

The discovery of Halicephalobus mephisto, a nematode ‘worm from hell,’ which thrives over two miles beneath the ground, has rewritten the textbooks on the bands within which live can evolve, raising hopes that such a subterranean migration could occur elsewhere on places like Mars or Enceladus.

The discovery of Halicephalobus mephisto, a nematode ‘worm from hell,’ which thrives over two miles beneath the ground, has rewritten the textbooks on the bands within which live can evolve, raising hopes that such a subterranean migration could occur elsewhere on places like Mars or Enceladus.

As [insert superlative here] as mephisto is, the bacteria on which this worm feeds are even more [insert an even stronger superlative here].

Recognized as a species of Firmicutes, this bacteria thrives on molecules produced as a byproduct of the radiation given off by naturally decaying Uranium breaking up water into peroxide. This means that like the bacteria around deep sea thermal vents, these Firmicutes exist independent of the rest of the biosphere.

These Firmicutes have carved out their own ecological niche entirely separate from photosynthesis-driven surface life. If life on Earth was wiped out by radiation from a nearby supernova or a massive asteroid impact, these little critters probably wouldn’t notice.

Nematodes tend to rate highly on any list of extremophiles because they have adapted to living anywhere from the Antarctic to the deserts of North Africa. When winter closes in on Antartica, these guys do what guys do everywhere when the winter snows start looming, they put some antifreeze in the radiator. Only these guys incorporate antifreeze (glycerol) in their blood.

Nematodes tend to rate highly on any list of extremophiles because they have adapted to living anywhere from the Antarctic to the deserts of North Africa. When winter closes in on Antartica, these guys do what guys do everywhere when the winter snows start looming, they put some antifreeze in the radiator. Only these guys incorporate antifreeze (glycerol) in their blood.

And this party trick isn’t reserved for microscopic creatures, the Antarctic ice fish does the same thing.

Tardigrades, or water bears, are a personal favorite, as these guys are complex creatures capable of being revived after spending a week in outer space, exposed to the harsh vacuum and solar radiation in a low Earth orbit.

Not only that, but tardigrades can be found in the Himalayas, at 20,000 ft above sea level, as well as down to 13,000 ft below the ocean. Tardigrades are exceptional in that they thrive in all extremes, not just in one niche area. They’ve been revived from temperatures as low as almost absolute zero, and can survive at upwards of 300F or 150C.

Like all extremophiles, tardigrades raise the prospect of life potentially existing elsewhere within the extremes of the solar system.

Deinococcus radiodurans is a bacterium that can survive a thousand times the radiation levels that would kill a human. Scale that up to three thousand times a lethal dose for us, and the survival rate is still over 37% for a given culture of radiodurans. Given how quickly bacteria multiply, this would barely phase the organism.

Deinococcus radiodurans is a bacterium that can survive a thousand times the radiation levels that would kill a human. Scale that up to three thousand times a lethal dose for us, and the survival rate is still over 37% for a given culture of radiodurans. Given how quickly bacteria multiply, this would barely phase the organism.

The surprising thing about radiodurans is that there’s nowhere on Earth that’s naturally exposed to these kind of radiation levels. These are the kinds of radiation levels we see around Jupiter, and that bacteria from the relatively benign third-planet out from the sun could thrive on a Jovian moon bathed in harsh radiation is astounding. In this regard, Io, Ganymede or Europa are suddenly looking quite promising in the hunt for extraterrestrial life.

Speaking of harsh environments, there are bacteria that can survive in hydrochloric acid (ph 1.5-3.5) in the human gut.

There’s even been bacteria revived from ice cores dated at over a hundred thousand years in age, highlighting how hardy microscopic life is in contrast to macroscopic life.

The dry valleys of Antartica, the driest place on Earth, offer a glimpse of the kind of life that could be possible on Mars. There’s little or no ice present in these frozen deserts, while what minuscule rainfall occurs on an annual basis freezes or evaporates within a day.

The dry valleys of Antartica, the driest place on Earth, offer a glimpse of the kind of life that could be possible on Mars. There’s little or no ice present in these frozen deserts, while what minuscule rainfall occurs on an annual basis freezes or evaporates within a day.

With mean temperatures around -35C (-90F), the only significant difference between Antartica and the highlands of Mars is the atmospheric composition and pressure. Fungi and bacteria exist within a few centimeters of the surface. With no appreciable water, they form a thin, dry crust, defying all expectations as to what is required for life to thrive.

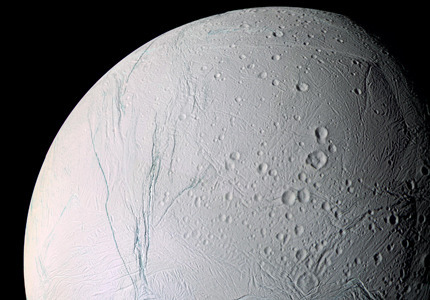

Even apparent “dead zones” on Earth, ocean and lakes starved of oxygen, have evolved anaerobic bacteria.

Even apparent “dead zones” on Earth, ocean and lakes starved of oxygen, have evolved anaerobic bacteria.

The more we look, the more we find life carving out an existence in the harshest environments on Earth.

Given the mechanisms by which Natural Selection drives evolution, and the advantages of specialization in dominating an environmental niche, all this shouldn’t be surprising, but it is carried to an extreme beyond anything we could have imagined, and that bodes well in the search for extraterrestrial life. As nice as it would be to find intelligent aliens, I’d settle for microscopic extraterrestrial life in the first instance, as we would learn so much from such a discovery.

It’s impossible to predict how successful SETI will be in searching for intelligent alien life, and the search for extraterrestrial life within the solar system might not find anything, and yet it may be that given the success of bacteria on Earth, both in terms of longevity, diversity and their tolerance of extremes, that we could find alien microbial life before we hear from ET.

Instead of looking completely implausible, our knowledge of extremophiles on Earth helps us to understand that life elsewhere within our solar system is plausible. I guess that makes NASA scientists extremophilephiles, as they love those organisms that love extremes.