We need to speak out about Child Abuse

If the Jimmy Savile case has taught us anything, it’s that we aren’t good at protecting young children from those who want to use them for their own sexual gratification. It’s also exposed the fact that Feminism hasn’t done a very good job of empowering women to shout out about sexual harassment.

Talk to any woman confidentially and they’ll tell you of their experiences. When I first started work as a shy teenager, being groped was just one of the office hazards - it was whispered around that Mr S from accounts wasn’t one to be caught alone in the photo-copying room with, and never let X get you cornered in the cloakroom. It just had to be endured - goodness! - a junior typist making a complaint against senior management? Never! Like the pervert in the cinema, the flasher in the park, or the elderly clerical groper at the harvest festival supper, it was one of the facts of life you had to come to terms with. Why, oh why, were we never able to stand up and shriek ‘get away from me!’. Why weren’t we able to complain?

It was all about the abuse of power. It’s a potent aphrodisiac. After I married, we were taken out to dinner by my husband’s employer with some clients, and his boss groped my legs with his hands throughout the meal under the tablecloth. I had to keep smiling and chatting to the clients and he knew that I would. Making waves wasn’t my style. But why didn’t I make a fuss? Why would it have been me who would have been blamed for ruining the dinner and probably losing the contract?

The other consequence of the Savile affair is that more and more women are beginning to talk about the abuse they suffered as children. The problem is much, much more common than anyone realises, but we don’t talk about it and as a result people have the impression that it’s rare and couldn’t possibly happen in their family. We need to talk about, not just Kevin, but Karen and Kirsty and Katherine. In this case it’s Kathleen who is coming clean. Those of you who are squeamish will probably stop reading the blog now. But this is a story of hope and optimism - abuse needn’t ruin children’s lives if we listen to them and protect them.

My paternal grandfather was a paedophile. He was a war hero, had been a champion boxer, was a charity worker in his community, a writer for the local paper and he ran an amateur dramatic society that toured the towns and villages of Cumbria. He was given medals, had letters from the Queen and was generally respected and looked up to. But there were people who knew something different. Some of his colleagues at work were shocked by the photographs he occasionally showed them of young naked girls, which he kept in his pocket. And (it transpired later) there had been an incident with a neighbour’s daughter which resulted in angry scenes and my grandparents moving house. In those days it was called ‘being interfered with’.

Then there had been an incident with a cousin, whose mother warned my mother that ‘Harry’ wasn’t to be trusted around children. My parents thought she was simply imagining things - they were very naive. We lived on a farm in a very rural location and my grandparents used to come out on the bus from Carlisle once a fortnight, stay for lunch and then go back in the evening. Sometimes they stayed overnight. I was about 9 at the time and my grandfather began cornering me in the house, when my mother was out helping my father on the farm, and getting me to touch him in ways I thought were disgusting. Why didn’t I say something to my mother? I’ve pondered that over and over. I think because I simply didn’t understand what it was all about and I didn’t have the language to explain. I’d been brought up to trust adults and to do what I was told.

It got worse. In the afternoons my grandparents would walk down the country lanes to the village school to collect me and my young brother (he was around 4) from the school. Mum was very glad of the break this gave her. My grandmother suffered from angina, so sometimes my grandfather came alone. And that is where hell really started. On one occasion he took us into the woods that lined the road, stripped me naked and tried to rape me in front of my small brother. It may have been my brother’s crying that stopped him going all the way.

I have a dim recollection, next morning when my mother was brushing my hair, of begging her not to let my grandfather pick me up from school. But when I got out of the classroom that afternoon, he was there again. I climbed over the playground wall at the back, with my brother, and came home across the fields - we both got scratched and muddy and I was told off for tearing my dress and not waiting for my grandfather. ‘Whatever possessed you?’ my mother asked.

When, years later, I asked what it was I’d said that alerted them to what was going on, I discovered that it wasn’t anything I’d said, but something my brother had blurted out. I know I was questioned and was very relieved to be able to tell them what had been happening. The miracle was that I was believed, because I was an imaginative child who had difficulty discriminating between what happened in my head and in the world around me. They were both equally real.

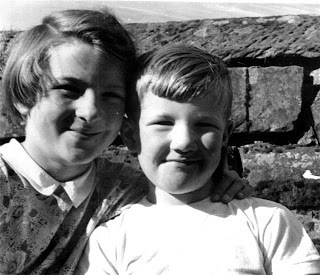

My brother and I aged about 9 and 4I remember a family conference (without my grandparents). Then I remember my grandmother asking why my father no longer spoke to his own father. I remember never being allowed to be alone with him again. I was allowed to hate him, told that he was a ‘bad man’, and never, ever was I made to feel I might have been even slightly to blame. It helped that I wasn’t the only family victim - there was a rumour that one of my uncles, accompanied by some friends, had met Harry in the street on his way home from work, put him up against a wall and punched him. He’d been threatened that if he ever touched one of us again, they would kick his balls to pulp. That was working class justice.

My brother and I aged about 9 and 4I remember a family conference (without my grandparents). Then I remember my grandmother asking why my father no longer spoke to his own father. I remember never being allowed to be alone with him again. I was allowed to hate him, told that he was a ‘bad man’, and never, ever was I made to feel I might have been even slightly to blame. It helped that I wasn’t the only family victim - there was a rumour that one of my uncles, accompanied by some friends, had met Harry in the street on his way home from work, put him up against a wall and punched him. He’d been threatened that if he ever touched one of us again, they would kick his balls to pulp. That was working class justice.When I was older, in my young teens, I had to make conscious efforts to keep out of the way of his groping hands at family events, and I was aware that he haunted children’s playgrounds. I was angry with my family for not going to the police, believing that they had not done so in order to protect my grandmother and the family reputation. I felt guilty (and still do) for all the child victims I was sure were out there, who had not had loving, secure families to protect them. I didn’t realise just how much their decision to keep the police out of it had contributed to my own well-being. When I began to study law and observed trials in the courts with the object of becoming a barrister, I became aware that if my parents had gone to the police, the process of law would have destroyed me. The adversarial court process is a meat-grinder that abuses children all over again and often breaks fragile human beings completely. We have to find a better way to prosecute abusers.

I am one of the lucky ones - I received what the victims of child abuse need in order to heal - I was believed, protected, allowed to hate, reassured that I was innocent. I was also in a secure loving family unit with other male role models I could love and respect without fear. I knew my paternal grandfather was a rogue male. Later, as an adult, I read his privately written memoirs and realised that he too had probably been an abused child. He was the illegitimate son of an Irish immigrant mother who took in lodgers who shared her children’s rooms and lived in the kind of poverty we can’t even imagine today. They were brought up as Catholics, but he was so fervently anti-catholic it makes me wonder about that too. In the first world war, he was gassed, shell-shocked and badly injured in the trenches at Ypres. Then he had the misfortune to marry a woman who hated sex and rarely allowed him into her bed. The things I read gave me a different picture of the man I’d grown up to hate. I found that I could feel compassion.

Harry in his WWI uniformIt took me a long time to write about my experience. The taboos around talking about it are still very strong. It first emerged as a poem, ‘War Hero’, eventually published in ‘Not Saying Goodbye at Gate 21'. The first time I read it to an audience I agonised for days about whether to read something so private and controversial (as I’ve agonised about whether to put up this blog). On the night, reading it was a much more emotional experience than I’d expected. But after the reading was over, a woman approached me as I was putting on my coat and told me, weeping copiously, that she too had been sexually abused by her grandfather and she had never been able to talk about it to anyone, ever. We put our arms around each other and wept together. I hope it helped her to tell someone.

Harry in his WWI uniformIt took me a long time to write about my experience. The taboos around talking about it are still very strong. It first emerged as a poem, ‘War Hero’, eventually published in ‘Not Saying Goodbye at Gate 21'. The first time I read it to an audience I agonised for days about whether to read something so private and controversial (as I’ve agonised about whether to put up this blog). On the night, reading it was a much more emotional experience than I’d expected. But after the reading was over, a woman approached me as I was putting on my coat and told me, weeping copiously, that she too had been sexually abused by her grandfather and she had never been able to talk about it to anyone, ever. We put our arms around each other and wept together. I hope it helped her to tell someone. Of course it’s not just girls who get abused, boys do too - we need to protect our children better. No point in telling them to avoid strangers - it’s more likely to be Uncle Bill, or even Aunty Trish - because women are abusers too (remember the Little Ted nursery scandal?) We need to give children better information about their bodies and what it’s ok for people to do to them. No namby pamby euphemisms - children can cope with truth. And we need to look out for them - all of us. It’s the culture of silence that allows paedophiles and sexual predators to operate.

Published on October 24, 2012 03:49

No comments have been added yet.