The System of Stoic Philosophy

Copyright (c) Donald Robertson, 2012. All rights reserved.

This article attempts to summarise some of the structured elements of the early Stoic philosophical system, such as the tripartite classification of the topics of philosophy, the virtues, the passions, and their subdivisions, etc., as reputedly described by the primary sources. It’s still a work in progress, see please feel free to post comments or corrections.

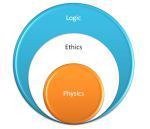

The Parts of Philosophy

From Diogenes Laertius (7.38-41)

Zeno introduced the tripartite division of philosophy in his book On Rational Discourse. Whereas some Stoics say the three parts of philosophy are mixed and taught together, Zeno, Chrysippus, and others, put them in the following order:

Logic

Physics

Ethics

However, Plutarch says that Chrysippus thought the parts should be studied as follows (Early Stoics, p. 9):

Logic

Ethics

Physics (and theology)

Cleanthes divided philosophy into six parts, however.

Dialectic

Rhetoric

Ethics

Politics

Physics

Theology

Several metaphors are used in conjunction with this tripartite division of philosophy. For example, philosophy is like an animal:

Logic = The bones and sinews

Ethics = The fleshier parts

Physics = The soul

Philosophy is like an egg:

Logic = The shell

Ethics = The egg white

Physics = The yolk

Philosophy is like a productive field:

Logic = The surrounding wall

Ethics = The fruit

Physics = The land and trees

Philosophy is like a city “which is beautifully fortified and administered according to reason.” According to Sextus Empiricus, Posidonius compared philosophy to an animal, as follows (Early Stoics, p. 9):

Physics = The flesh and blood

Logic = The bones and sinews

Ethics = The soul

Ethics & The Virtues

From Diogenes Laertius (7.84-131).

The early Stoics define “the good” as encompassing three senses:

The most fundamental sense is that through which it is possible to be benefitted, which corresponds mainly to the virtues

In addition, the good includes that according to which being benefitted is a typical result, which refers both to the virtues and to specific virtuous actions

Finally, the good includes that which is such as to benefit, namely the Wise man himself, true friends, and the gods, who engage in virtuous actions and possess the virtues

From another point of view, the good is described as being both beneficial (healthy?) and honourable or praiseworthy.

Although Zeno and Cleanthes did not divide things in such detail, the followers of Chrysippus and others Stoics classify the sub-divisions of ethics as follows:

On impulse

On good and bad things

On passions

On virtue

On the goal

On primary value

On actions

On appropriate actions

On encouragements and discouragements to action

Diogenes Laertius says that whereas Panaetius divided virtues into two kinds (theoretical and practical), other Stoics divided the virtues into logical, ethical and physical. According to Aetius also, there are three categories of virtue, which correspond with the three divisions of philosophy: physics, ethics, and logic (Early Stoics, p. 9). He doesn’t say what these virtues are, but we might speculate:

Physics = Self-Control (Courage & Moderation, two of the cardinal virtues)

Ethics = Justice

Logics = Wisdom (or Prudence)

Most Stoics appear to have agreed that there are four “primary” virtues, common to other ancient schools of philosophy:

Prudence or Practical Wisdom (Phronesis), sometimes just called Wisdom (Sophia), which opposes the vice of “ignorance”

Justice or Integrity (Dikaiosune), which opposes the vice of “injustice”

Fortitude or Courage (Andreia), which opposes the vice of “cowardice”

Temperance or Moderation (Sophrosune), which opposes the vice of “wantonness”

These are defined as forms of knowledge (q.v., Stobaeus in Early Stoics, p. 125-130):

Prudence is knowledge of which things are good, bad, and neither; or “appropriate acts”.

Temperance is knowledge of which things are to be chosen, avoided, and neither; or stable “human impulses”.

Justice is the knowledge of the distribution of proper value to each person; or fair “distributions”.

Courage is knowledge of what is terrible, what is not terrible, and what is neither; or “standing firm”.

The cardinal virtues are also sub-divided as follows:

Prudence takes the form of deliberative excellence, good calculation, quick-wittedness, good sense, good sense of purpose, and resourcefulness.

Temperance takes the form of organisation, orderliness, modesty, and self-control.

Justice takes the form of piety, good-heartedness, public spiritedness, and fair dealing.

Courage takes the form of endurance, confidence, great-heartedness, stout-heartedness, and love of work.

A famous slogan of Epictetus is usually translated as “bear and forbear” or “endure and renounce”. This can perhaps be seen to correlate with the two virtues relating to self-control in the broad sense: courage and temperance. It’s possible that these two complementary virtues both correspond somehow with the discipline of Stoic physics and with the passions, as follows:

Endure (bear), through the virtue of courage, whatever irrational pain or suffering would normally be feared and avoided

Renounce (forbear), through the virtue of temperance (or moderation), whatever irrational pleasures would normally be desired and pursued

According to Chrysippus and other Stoics, the main examples of indifferent things, being neither good nor bad, are listed as pairs of opposites (Diogenes Laertius, 7.102):

Life and death

Health and disease

Pleasure and pain

Beauty and ugliness

Strength and weakness

Wealth and poverty

Good reputation and bad reputation

Noble birth and low birth

…and other such things.

The Passions

According to Zeno, the passions are to be defined as judgements or movements of the soul, which are (Diogenes Laertius, 7.109):

Irrational,

Unnatural, or,

Excessive

According to Zeno, the most general division of these irrational passions is into four categories:

Pain (or suffering)

Fear

Desire

Pleasure

These can be subdivided as follows (following Diogenes Laertius but also Stobaeus, in Early Stoics, pp. 138-139:

Pain is an “irrational contraction” of the soul and can take the form of pity, grudging, envy, resentment, heavyheartedness, congestion, sorrow, anguish, or confusion. Or according to Stobaeus, envy, grudging, resentment, pity, grief, heavyheartedness, distress, sorrow, anguish, and vexation.

Fear is the “expectation of something bad” and can take the form of dread, hesitation, shame, shock, panic, or agony. Or according to Stobaeus, hesitation, agony, shock, shame, panic, superstition, fright, and dread.

Desire is an “irrational striving” and can take the form of want, hatred, quarrelsomeness, anger, sexual love, wrath, or spiritedness. Or according to Stobaeus, anger (e.g., spiritedness, irascibility, wrath, rancor, bitterness, etc.), vehement sexual desire, longings and yearnings, love of pleasure, love of wealth, love of reputation, etc.

Pleasure is an “irrational elation over what seems to be worth choosing” and can take the form of enchantment, mean-spirited satisfaction, enjoyment, or rapture. Or according to Stobaeus, mean-spirited satisfaction, contentment, charms, etc.

In addition to the irrational, excessive or unnatural (unhealthy) passions, there are also corresponding “good passions”. These fall into three categories, because no good state corresponds with emotional pain (suffering) or contraction of the soul (Diogenes Laertius, 7.116).

Joy or delight (chara), a rational elation, which is the alternative to irrational pleasure

Caution or discretion (eulabeia), a rational avoidance, which is the alternative to irrational fear

Wishing or willing (boulêsis), a rational striving, which is the alternative to irrational desire

These good passions can be subdivided as follows:

Joy can take the form of enjoyment/delight (terpsis), good spirits/cheer (euphrosunos), or tranquility/contentment (euthumia)

Caution can take the form of respect/restraint/honour (aidô) or sanctity/purity/chastity (agneia)

Wishing can take the form of goodwill/favour (eunoia), kindness (eumeneios), acceptance/welcoming (aspasmos) or contentment/affection (agapêsis)

In other words, a distinction can be made between rational and irrational passions as follows:

Elation (eparsis) can take the form of rational joy (chara) or irrational pleasure (hêdonê)

The impulse to avoid something (ekklisis) can take the form of rational discretion (eulabeia) or irrational fear (phobos)

The impulse to get something (orexis) can take the form of rational willing (boulêsis) or irrational craving (epithumia)

There is no rational form of pain or suffering (lupê), in the Stoic sense

The good passion of caution (or discretion) appears to particularly resemble the virtue of temperance. The good passion of wishing (or willing) appears to mainly encompass love (agapêsis), and related affects, such as goodwill, kindness, acceptance and affection. This is the rational alternative to anger and sexual lust, or irrational desire.

Filed under: Stoicism Tagged: philosophy, stoic, stoicism