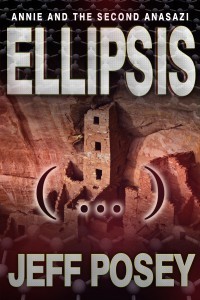

“Socrates was Right,” Annie Flash Fiction by Jeff Posey

Coming in 2013

A flash fiction piece in preparation for the novel-in-progress Ellipsis: Annie and the Second Anasazi, by Jeff Posey, set in the year 2054. Sign up for notification by email here.

Posts. As far as Annie could see. Like an unfinished fence that marched as straight as an Anasazi road across the desert, needing only cross-wires to be complete.

“It’s an experiment,” said Serles. “We’ll stretch water sheets between them and plant like the ancient ones where the output drips: corn deeply sowed, beans, squash. We’re thinking with these, even a desert could feed people. Millions of people.”

“What’s the downside?” Annie knew as well as anybody the price humans paid for the unintended consequences of past “experiments” such as these that scaled up beyond what nature could support.

Serles puckered his face. Ever the scientist, he wouldn’t dismiss the notion that his Serles Sheets, which he called “water sheets,” could provoke some kind of unforeseen damage. “Native animals won’t be used to it,” he said.

“It’ll change the soil over the long run,” added Theo.

Serles nodded. “If enough sheets went up, it could change rainfall patterns by creating large masses of dry air.”

“Insects will love munching on the new garden,” said Theo.

“There’s one worse than all of those combined,” said Annie. They looked at her. “Millions of people.”

They nodded. An ages-old dilemma. Grow the population, ruin the planet. The only way to imagine a decent future was to maintain a super-low human population or an exceptionally unobtrusive way for millions to live without fouling their nests. That way hadn’t yet been found. To Annie’s thinking, it would require a strong coercive central government aligned with nature and science instead of religion and politics. In the history of humanity, that tended to result in revolution rather than a sustainable stasis.

“That gets into things science can’t solve,” said Serles.

“Guns and God can’t, either,” said Theo.

“So we leave it to chance?” asked Annie. “We can’t do experiments that might feed the world while knowing it could lead us to nearly commit global suicide again.”

Serles shrugged. “Boom and bust is a pretty common phenomenon among living things.”

“What, bacteria? Rabbits? Mosquitoes?” Annie stood. She refused to believe that collective humanity would always predictably behave like vermin or germs. There had to be something.

“Socrates was right,” said Theo.

“What?” asked Annie, though she’d heard her father say the same thing.

“Oh, the democratic state put him to death because he thought democracy would fail about like it has. He said it much more nicely, but he believed the voting majority was too stupid to rule itself. He proposed a special state-supported class of public servants who would be educated and trained for their duties, chosen for intellect and aptitude rather than bloodlines or the ability to fight.”

“That would have its own set of unforeseen consequences,” said Serles. He shook his head again. “Can you educate people into being altruistic and self-limiting? I doubt it.”

“So what do we do?” asked Annie. “Use science to come up with tools for people to thrive and just hand it to them, and then watch them use it to nearly kill us all?”

Serles raised his hands in a gesture of helplessness. “Science doesn’t do that part.”

“Maybe we’re not worth saving,” said Theo. “As a species. Maybe the best thing is to let us kill ourselves off so the planet can go back to doing whatever it does without us.”

“Wow,” said Annie. “So keep the Serles sheets to ourselves. And the nano-carbon materials. Just let the Reagan Newcastles of the world ruin it in the name of God and Government?”

“Maybe that’s God’s plan all along,” said Theo. “Maybe He’s sitting up there laughing his ass off right now. We’re his entertainment channel.”

“Science can’t make those kinds of value judgments,” said Serles, looking at Annie, ignoring Theo.

“No,” said Annie, “people do.”

“If we release the Serles Sheets to the world,” said Theo, “I wager that within a decade, some regime somewhere will find a way to turn it into a weapon of mass destruction.”

Serles looked from Theo to Annie. “You two make it sound hopeless. I refuse to believe that.”

“Me too,” said Annie.

“Not me,” said Theo. “Humans are doomed.”

A hot, dry breeze stirred. A dust devil swirled along the white flats beside the incised Chaco wash.

“We need a new Socrates,” said Annie. “Combined with a Thomas Jefferson, and…I don’t know who else. Einstein, maybe.”

“Jesus,” Theo said. “We need a new martyr. Somebody to murder and then worship.”

“Jesus,” muttered Serles.

“Yep,” said Theo. “Jesus Christ Himownself.”

Ellipsis: Annie and the Second Anasazi, set in 2054 A.D., is about a migration of intellectuals into the deserts of New Mexico where people live like the ancient ones because of changing climate coupled with an intolerable mix of politics and religion that rises in the cities of the American South. Annie is the daughter of Tucker and Lydia Roth of Girl on a Rock. Serles is the ancestor of the character by the same name in The Pump Jack Potion. Theo is the son of Sean O’Brien from Anasazi Runner. For an excellent and readable book about Socrates, see I.F. Stone’s The Trial of Socrates.