IPDW2025 — We All Eat Feta: Reflections on the First Production Design Gathering

I have been struggling to describe the ineffable.

In a week in October 2022, 260 production designers from 36 countries gathered on a Greek island of pines. We experienced something so profound — together — that I know we are forever changed.

This was ‘The Gathering’: the first time in history that production designers had come together for a long weekend of panels, workshops, shared meals, sketching sessions, late-night dancing, and communal reflection.

I had my “a-ha moment” very early on. On the ferry to Spetses, I noticed Jack Fisk — legendary production designer of The Tree of Life (2011), Mulholland Drive (2001), The Revenant (2015) — eating a piece of feta. I thought to myself:

“wow, I eat feta too.”

It was a silly, simple thought. But it was also everything. Here we were, peers at the same table, bound not by credits or years of experience, but by our shared love of storytelling. That realisation — that we all eat feta — became my shorthand for what unfolded: the collapse of distance and the recognition of ourselves as a global community of makers.

image 1: On the ferry to Spetses

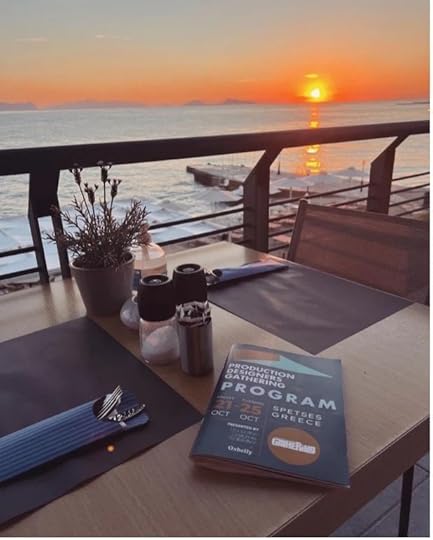

Image 2: Breakfast views over the Aegean, with “The Gathering” Program.

Why “The Gathering” MatteredProduction designers rarely meet outside the context of awards shows or guild events. Our work is deeply collaborative, yet our careers are strangely solitary. Each of us is embedded in the ecosystem of a particular production, framed by schedules and deliverables.

It was the vision of Inbal Weinberg and Kalina Ivanov who founded the Production Designers Collective as a space for community that made The Gathering possible. By calling us to Spetses, they created a space of recognition. As Kalina wrote at the time, “We’re starting a new chapter in film mythology, and what’s a better place to do it than in Jason and the Argonauts’ backyard?”

For the first time, the invisible became visible: the production designer’s role not as ‘below-the-line’ technicians, but as co-creators of narrative worlds, spatial storytellers who shape the very architecture of screen stories.

Image 3: A toast to Inbal Weinberg and Kalina Ivanov, founders of the Production Designers Collective.

Image 4: A folio of production designers sketching en plein air along the Spetses waterfront.

Voices in the PinesThe days on Spetses unfolded as a chorus of perspectives, giving voice to the tacit knowledge of our craft while also exposing its challenges. Mornings were spent in Cinema Titania, the island’s open-air cinema, where curated panel discussions were less about how to design and more about why we design: what it means to bring imagination into form within an industry defined by truncated schedules, shifting technologies, and resourcing constraints. Afternoon workshops took us to the Anargyrios & Korgialenios School (AKSS), its neoclassical halls and pine-lined pathways steeped in history, a place that once inspired John Fowles’s The Magus. Evenings ended with dinners under the stars and one unforgettable Zorba dance in a festoon-laden courtyard.

Image 5: Cinema Titania, the island’s open-air cinema where morning panels took place

Image 6: The pine-lined grounds of the Anargyrios & Korgialenios School (AKSS), home to afternoon workshops

What emerged in those spaces was a series of provocations that would reshape how we understood our work. Jean-Vincent Puzos, enigmatic French designer behind Amour (2012) and Beast (2022) urged us to, “learn how to disobey — analyse everything. Have courage. Creativity is poetry, creativity is surprise. You either obey or you challenge.” Beside him, K.K. Barrett, who gave Her (2013) its futuristic intimacy, warned against mediocrity, “the script is not a bible, it is a sketch of a map. Go beyond the obvious. The opposite of obvious is original.” He described the common purpose of director and designer as one of elevation and surprise. Together, they reminded us how easy it is to fall in service to the ordinary, when in fact we are hired to interpret, interrogate and inspire.

Inbal Weinberg, whose textured work amongst the pines on The Lost Daughter (2021) brought us to Spetses, responded: “All cinema is a dream. Dreams don’t have to be responsible.” She spoke of wandering through libraries, exhibitions, and galleries, of the importance of staying open to the unexpected, of research as a way of always going deeper. I thought of my own students, often tempted by Pinterest algorithms, and how valuable it is to model what she calls, “the meandering moments” of research.

There was pragmatism too. Jeannine Oppewall, Oscar-nominated for films including L.A Confidential (1997) and Pleasantville (1998) said it best in her resonant Boston accent, “Things change!” For all our drafted plans, previs and white card models, production design is made in flux, and our art departments needs to move with it.

The conversation also turned, inevitably, to labour. Kalina Ivanov reminded us that hierarchies are unavoidable but must be managed with kindness. David and Sandy Wasco, Oscar winners for La La Land, encouraged us to acknowledge where the ideas come from, to give credit to our teams. “We are in the business of collaboration,” they said, an important reminder in an industry that systemically privileges individual authorship over the distributed reality of creative labour.

Others pushed further. Jamie Lapsley, speaking from a career built upon richly diverse collaborations, called out the culture of presenteeism: “We are employed for our ideas, not our time… We need to break down the officeness of the office.” Her words hit me harder than I expected. How many times have I measured my worth by hours logged?

Visibility, or rather, our lack of it, became a recurring theme. Fiona Donovan, representing the Australian Production Design Guild, called for parity between design, costume, and cinematography. The evidence is stark: despite Wikipedia listing directors, writers, producers, cast, cinematographers, editors, and composers for every film, the production designer and costume designer are consistently absent. The same is true across festival programs worldwide. “Let’s not compete,” said Miranda Cristofani, a leading voice in production design advocacy, “we are better together.”

Then came the ecological reckoning. Blair Barnette, chair of the British Film Designers Guild, put numbers to our work: a single blockbuster produces 3,500 tons of carbon — the same as flying a full Airbus A318 around the world 15 times. The gasp in the room was collective. It reframed our sets, our materials, our choices.

Virtual production emerged as the most galvanizing topic of discussion. James Chinlund, whose credits include The Lion King (2019) and The Batman (2022) challenged us to reclaim virtual space: “Virtual production allows designers to finish our thoughts. That’s our space. We should reclaim it.” His words were both a provocation and a call to arms. Udo Kramer, who designed the labyrinthine world of Netflix’s 1899, showed what this means in practice. Pipelines had to be reinvented, and new roles carved out. His case study revealed both the complexity and the creative potential: the craft is evolving rapidly, and we have the opportunity to shape that transformation, to dissolve barriers between the Art and VFX departments and ensure holistic world-building from conception to completion.

This vision resonated deeply with my own experience as Discipline Lead in Production Design at Australia’s National Film School. At AFTRS, I have worked to make virtual production integral to our curriculum, recognising that it represents more than new tools, it’s a fundamental shift toward collaborative, non-linear creation. Unlike traditional filmmaking’s sequential workflow, virtual production collapses the divisions between pre-, production, and post- into a simultaneous, iterative process. This transformation demands that we rethink how we teach design, moving beyond technical skill-building to embrace integrated approaches where production design and VFX merge into continuous world-building.

Image 7: Panel discussion on Fostering Creativity at Cinema Titania

Image 8: Workshop circle at AKSS, where designers, educators, and students shared experiences. image credit: production designers collective (PDC)

The AmphitheatreOn the final evening, as workshops ended, we made a slow pilgrimage up the pine-lined path to the amphitheatre that crowns the island.

One by one, voices carried across the stone circle. Rick Carter, the extraordinary world-builder behind our most beloved realms including Jurassic Park (1993), Avatar (2009), and Star Wars: Episode VII and IX (2015, 2019), opened our church. It was fitting. Rick’s wisdom had resonated as a through-line across the panels, workshops, and late-night dinner conversations throughout the week. He evoked the words of Socrates: “True knowledge exists in knowing that you know nothing.” For Rick, the essence of creativity lies in discomfort; “Of course it hurts. The trick is not to mind it.”

Fiona Crombie, Australian production designer of The Favourite (2018) and Cruella (2021) reflected on being in the company of people who had informed her thinking. Thomas Walsh, past president of the ADG, evoked the old Hollywood Cinemagundi Club, a community he felt had been reborn in these pines.

Tigerlily, a student whose third favourite colour is pink, set aside vulnerabilities and spoke of what it meant to be surrounded by people who loved what she is currently learning to love.

Some spoke of fear, others of joy. Akin McKenzie called it a “vibration.” Alex Whittenberg described it as our “apotheosis”: the highest point of something, brushing against the sacred.

As the lilac hues of dusk deepened, Kalina closed the circle. We leave this island, she told us, with white passports: production designers of the world.

Image 9: The pilgrimage through the pines up to the island’s amphitheatre.

Image 10: A historic first: 260 production designers gathered in the amphitheatre at Spetses. Image credit: production designers collective (PDC)

Beyond the IslandThe Gathering was not a retreat. It was a cultural event that altered the fabric of our craft.

It disrupted the production culture that keeps us siloed and invisible. It reminded us that though our work is embedded in hierarchies, we can choose how to manage them: with generosity, transparency, solidarity.

It reframed authorship in cinema. The old myth of the singular auteur began to give way to a more collective, distributed understanding where production designers are recognised as co-authors of screen space.

It exposed the structures of our industry that must change: the carbon cost of our builds, the inequities of our labour systems, the need for new collaborative frameworks in virtual production pipelines, the absence of recognition amongst our colleagues.

The legacy of Spetses is not only emotional but structural. The Gathering also saw the founding of the Production Design Research and Education Network (PD-REN), first imagined over lunch on the balcony of the Poseidonion Hotel and now connecting more than 400 researchers and educators worldwide.

And perhaps most importantly, it cultivated a sense of identity. No longer solitary practitioners fighting for recognition in isolation, but a global community.

When I think back to Spetses, I remember the panels and workshops, the amphitheatre, the late-night dancing, the sketches completed on cobblestones, the meandering conversations over dinner.

But mostly, I remember the feeling: that for the first time, I was not alone in this craft.

The Gathering gave us white passports, symbolic citizenship in a borderless community of storytellers. It asked us to carry that sense of connection back into our guilds, our classrooms, our studios. And it left us with an unfinished task: to keep gathering, to keep pushing, to keep challenging the industrial conditions that limit us.

What began in 2022 has already continued, with another Gathering in 2024 and plans for a biennial rhythm. The conversations are living.

Because in the end, what we learned on that island is simple: we all eat feta. And in that recognition lies the possibility of a new culture of cinema, one where production design is not hidden but celebrated, not solitary but collective, not obedient but original.

Until we gather again.

Image 11: The closing feast in the AKSS courtyard, lit with festoon lights. Image credit: PDC

Video: Dancing in a dream, the final celebration under the stars. Video credit: Alex Whittenberg.

BiographyNatalie Beak is a Production Designer with twenty years’ experience across film and television in Australia and the UK. A graduate of the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS), she was the inaugural recipient of the Thelma Afford Award for excellence in Costume Design and has since built a reputation for an inclusive and collaborative design practice. Her screen credits include the Berlinale Crystal Bear-winning short Franswa Sharl (2009), the ABC’s acclaimed comedy series Black Comedy (2014-2020), the First Nations Anthology feature We Are Still Here (2022), the Stan drama Year Of (2023), and Bus Stop Films’ debut feature Boss Cat (2026).

Alongside her professional practice, she is Discipline Lead in Production Design at AFTRS and a founding committee member of the Production Design Research and Education Network (PD-REN). Her forthcoming chapter will appear in Perspectives on Production Design: Practice, Education and Analysis (University of Westminster Press).

Henry Jenkins's Blog

- Henry Jenkins's profile

- 184 followers