Columbus Day

Many people are unaware that Columbus made not just one voyage but four; others are surprised to learn that he was brought back in chains after the third voyage. Even fewer know that his ultimate goal, the purpose behind the enterprise, was Jerusalem! The 26 December 1492 entry in his journal of the first voyage, hereafter referred to as the Diario, 3 written in the Caribbean, leaves little doubt. He says he wanted to find enough gold and the almost equally valuable spices “in such quantity that the sovereigns… will undertake and prepare to go conquer the Holy Sepulchre; for thus I urged Your Highnesses to spend all the profits of this my enterprise on the conquest of Jerusalem” (Diario 1492[1988: 291, my emphasis]).4 This statement implies that it was not the first time Columbus had mentioned the motivation for his undertaking, nor was it to be the last.5 Columbus wanted to launch a new Crusade to take back the Holy Land from the infidels (the Muslims). This desire was not merely to reclaim the land of the Bible and the place where Jesus had walked; it was part of the much larger and widespread, apocalyptic scenario in which Columbus and many of his contemporaries believed.

That from an article by Carol Delaney of Stanford, “Columbus’s Ultimate Goal: Jerusalem.”

Columbus knew from Marco Polo that there was a Great Khan somewhere to the west/east, and that this Khan had requested emissaries from the Pope. So possibly the Khan could be an ally against the Muslims.

Columbus and the other conquistador types commissioned by the King and Queen of Spain must be seen in the conquest of the Reconquista, the 700 year effort to drive Islam from Iberia. Cortes, for example, was a religious fanatic, who used the Spanish word “moscas” or mosques to describe the temples he found in the land of the Aztecs.

(Ridley Scott gets at some of this in 1492: Year of Discovery. My mom at least wanted to walk out of this movie once it gets to the torturing. Sigourney Weaver plays Queen Isabella.)

Delaney expands from Columbus’s religiosity to some bigtime thoughts on how we, today, may not be able to grasp what “religion” meant to someone like Columbus:

The modern understanding of religion did not fully emerge until the late nineteenth century when scholars began to attach “-ism” to make substantives out of adjectives—Buddhism rather than Buddhist, Hinduism rather than Hindu—thus making a ‘religion’ by separating out the spiritual elements from a whole way of life or culture that included ethnicity, language, food, dress, and other practices (see Smith 1962; Rawlings 2002). In reality, however, science, technology, and religion can be and are easily and seamlessly combined. For example, I found Turkish villagers, while mostly illiterate and uneducated, could discuss, understand, make, use, and fix a variety of modern machines and equipment including automobiles, telephones, and television sets; they could talk about international and national politics with more sophistication than most Americans, and they understood the economic networks with which their lives were entangled. They would appear to have a thoroughly modern consciousness. But staying long, getting to know them, and “pushing the envelope,” revealed to me how, at a much deeper level, they lived within a completely Islamic cosmology or worldview. That worldview encompassed their lives, it was the context within which they lived, and it provided answers to the perennial questions: who are we, why are we here, where are we going? It also affected the way they dressed, the food they ate, their practices of personal hygiene, the way they moved, and their spatial and temporal orientations (see Delaney 1991). It was inseparable from the rest of their lives, not something they practiced only on Fridays, the Muslim holy day, or by keeping the fast of Ramadan. Though they evinced varying degrees of devoutness, secularism was not an option. They believed their views were self-evident to any thinking person and they could not understand why I could not accept Islam and, in their terms, submit and become Muslim. Islam, to them, is not one religion among others; it is “Religion.” It is the one true religion given in the beginning to Abraham, and Muhammad was merely a prophet recalling people to that original faith. They had heard of Christianity, of course, and questioned me about it. But to them it was not a separate, equally valid religion, but rather a distortion of the one true word, the one true faith.

Just so did Columbus and his contemporaries view the sectas of the Jews and Muslims. His statement about freeing the Indians from error shows that religion was not a matter of choice but of right or wrong—there was only one right way. Indeed, they really had no conception of alternatives. The Reformation had not yet begun, and Judaism and Islam were seen not as different religions but as erroneous, heretical sects

Like a good anthropologist she quotes Clifford Geertz:

The anthropological critique of this position has been insistent: “[T]he image of a constant human nature independent of time, place, and circumstance, of studies and professions, transient fashions and temporary opinions, may be an illusion, that what man is may be so entangled with where he is, who he is, and what he believes that it is inseparable from them” (Geertz 1973: 35). In other words, there is no backstage where we can go to find the generic human; humans are formed within specific cultures. This does not mean that cultures are totally closed or that there is no overlap; one can learn another culture—that is, indeed, what anthropologists do during fieldwork. But if we are to understand Columbus (or anyone else), we must attempt insofar as is possible to reconstruct the world in which he lived. While some historians writing about Columbus appear to do this, they still, in my reading, project a modern consciousness onto him, leaving the impression that the time and place are merely “transient fashions.”

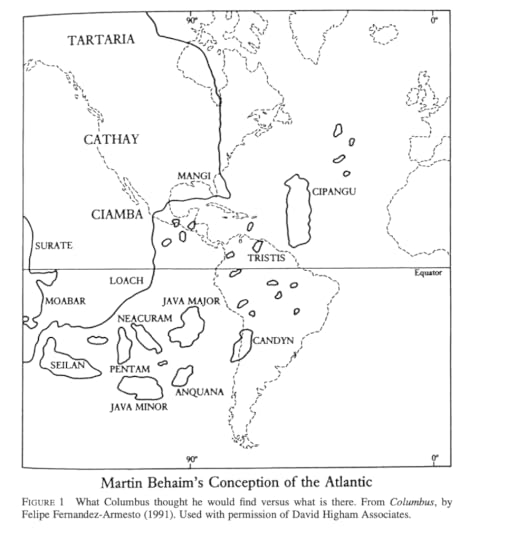

Delaney includes a great map, which I steal:

Since I was a kid the tone around Columbus has been a lot less “In fourteen hundred ninety two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue” and more he was a genocidal colonialist. But applying our concepts in moral judgment of these figures of the past seems not that far from Columbus applying his concepts to the native people he discovered. Then again, evolving our conceptions and adjusting our heroes as we go seems healthy, right?