Big vs. Small Character Arcs: Understanding the Degrees of Change in Storytelling

Not every story needs a protagonist who undergoes a sweeping, life-altering transformation. Many memorable tales hinge on smaller, quieter shifts in perspective—or even on characters who stay true to themselves from beginning to end. Writers often hear that character arcs must be dramatic to be meaningful, but the truth is arcs exist on a spectrum. Big character arcs can redefine a protagonist’s entire worldview, while small character arcs can reveal subtle but powerful growth that shapes the story in more understated ways. Understanding when to use a big arc, a small arc, or even a Flat Arc can help you choose the right level of change for your characters and keep readers invested from page one.

Not every story needs a protagonist who undergoes a sweeping, life-altering transformation. Many memorable tales hinge on smaller, quieter shifts in perspective—or even on characters who stay true to themselves from beginning to end. Writers often hear that character arcs must be dramatic to be meaningful, but the truth is arcs exist on a spectrum. Big character arcs can redefine a protagonist’s entire worldview, while small character arcs can reveal subtle but powerful growth that shapes the story in more understated ways. Understanding when to use a big arc, a small arc, or even a Flat Arc can help you choose the right level of change for your characters and keep readers invested from page one.

When I write about character arcs, I use sweeping terms about overcoming the Lie the Character Believes in pursuit of the thematic Truth. We talk about your character encountering Doorways of No Return, Moments of Truth, and Dark Nights of the Soul. All of these terms sound epic because they are symbolic. This means they can be applied in different stories to varying degrees of intensity. Just as in our own lives, some character arcs will rock the very foundations of the earth, while others may only offer a comparatively tiny realignment of perspective (perhaps as a building block toward one of those earth-shattering changes later on, but perhaps not too).

A while back, Tom Dell’Aringa emailed me with the following observation and query:

I’ve been following your stuff for a while. I was watching one of your videos on beginnings because I write a series, where the main character and his sidekick don’t change (like Jack Reacher or Jack Ryan, etc., although SF). While I always try to have some issue the main character is working through, he can’t go through some amazing transformation each book. Part of the joy of a series is sticking with a character you like, with all their pros/cons…. I wonder if you had thoughts on how to approach a series while living into the structure you have set out….

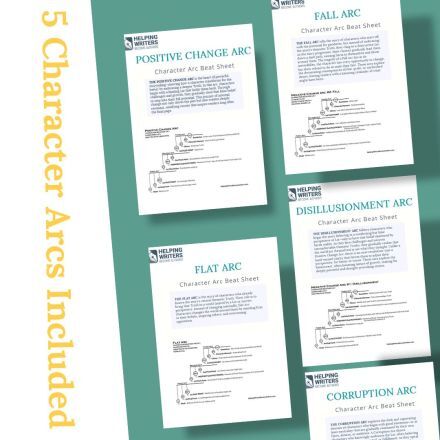

First of all, it’s important to recognize not every story will feature a Change Arc. Particularly in series, many characters demonstrate Flat Arc characteristics in each episode. This allows the story’s primary structures to remain unchanging, which allows steadfast characters to represent the story’s Truth to other characters—and therefore to be the one who prompts change rather than the one who changes. (If you’d like a hands-on tool for identifying and planning these different types of arcs, take a look at my Character Arc Worksheets.)

Character Arc Quick Guide (Bundle of 5 Worksheets)

It’s also possible to write stories that really don’t present much of an arc at all, although this is trickier since if the characters do not change, then it is difficult to create any true sense of movement or meaning within the plot itself. Most of the time, if you really look for it, even in tricky stories, you can still identify the underlying symbolic landmarks of some kind of arc, either in the protagonist or the supporting characters.

With all of that in mind, it’s important to remember you can feature a Change Arc without it necessarily having to offer tremendous transformation. When we speak of a Change Arc (whether Positive or Negative), we are simply referring to the fact that the character changes perspective in some way. Sometimes this can be a life-changing paradigm shift, but sometimes the change can be quite small (although it must still be consequential to the story). Particularly in plot-forward stories, the thematic Truth a character learns might even be something practical about the plot mechanics (e.g,. whodunit) rather than a deep personal or social insight. (For my money, however, stories are easily upleveled when the two go hand in hand.)

In short, character arcs in different stories won’t all look alike or carry the same weight. From here, we’ll break down the difference between big arcs, small arcs, and Flat Arcs, and explore how you can choose the right degree of change to best serve your story.

In This Article:Big Character Arcs and How Transformation Redefines the ProtagonistSmall Character Arcs and How Quiet Shifts Can Still Grip AudiencesFlat Arcs and How Characters Stay True While Still Driving the PlotBig Character Arcs and How Transformation Redefines the ProtagonistWhen we think of “thematic” stories, they are usually ones in which the character arcs are so big they completely redefine the characters’ worldviews and perhaps even the world itself. Like all character arcs, these changes are founded upon the central polarity between a Lie the Character Believes and the opposing Truth. At its simplest, this Lie is a limited perspective, while the Truth acts as a corrective by providing at least a slightly more expanded and functional advancement on that perspective.

In big Change Arcs, this conflict between Lie and Truth tends to be dramatic. This raises the stakes because the transition into the new perspective will all but demolish the character’s previous perspective. This inevitably involves a personal ego death and a transformation of personal identity (i.e., how characters view themselves). Likely, it will also play out in dramatic fashion in the external plot. Characters will have much to gain or much to lose depending on which perspective they end up embracing.

For Example:

A clear example of a dramatic Positive Change Arc can be seen in Schindler’s List. At the beginning, Oskar Schindler believes the Lie that his worth and power come from wealth, status, and self-interest. His identity is bound up in being a profiteer who exploits the war for personal gain. Over the course of the story, he is confronted with the Truth that real value lies in human life and moral responsibility.

Embracing this Truth demolishes his former worldview and forces him through a profound ego death, reshaping how he sees himself and his place in the world. Importantly, this transformation is not just personally dramatic: it also plays out against the larger system of Nazi Germany, where Schindler’s new Truth is in direct conflict with a regime fighting to assert its own destructive “truth” as socially preeminent. His decision to resist this system is not only perilous to him personally, it also highlights how a big Change Arc reverberates outward. The character’s internal shift becomes a force of external opposition in a dangerous world, raising both personal and thematic stakes to their highest pitch.

Oskar Schindler’s transformation in Schindler’s List is a powerful example of a big character arc. (Schindler’s List (1993), Universal Pictures.)

These dramatic personal and social stakes are true whether the character ends up in a Positive Arc from Lie to Truth or in a Negative Arc from Truth to Lie.

For Example:

The Banshees of Inisherin shows a powerful example of how a Negative Change Arc demolishes identity and spirals outward into destruction. At the start, both Pádraic and Colm have perspectives that, while limited, still allow for human connection: Pádraic clings to the Lie that being “nice” and “happy” will guarantee him love and belonging, while Colm seeks significance by isolating himself to pursue art, believing the Lie that human relationships are expendable in the quest for legacy.

As the story progresses, each man is drawn deeper into his respective Lie. Pádraic’s desperation to hold on to friendship corrodes his innocence, while Colm’s rejection of the relationship becomes increasingly violent and self-mutilating. These internal disintegrations don’t remain private. Just as in big Positive Arcs, in which the Truth collides with the larger world, here the embrace of the Lie clashes with the community, escalating conflict and despair. By the end, both characters have been transformed by the loss of whatever humanity and hope they once held. Their Negative Arcs show how a shift from Truth to Lie can unravel not only personal identity but also the fragile social bonds of an entire world.

In The Banshees of Inisherin, Colm and Pádraic’s relationship shows how Negative Change Arcs can unravel both identity and community. The (Banshees of Inisherin (2022), Searchlight Pictures.)

Small Character Arcs and How Quiet Shifts Can Still Grip AudiencesMany stories feature smaller character arcs with lower stakes. In these stories, the Lie/Truth will be less obviously mind-bending and ego-threatening. The thematic premise might span the gamut from “learning a moral lesson” (e.g., “be more loving”) to simply “seeing something in a new light” (e.g., “maybe my life is more interesting than I thought”) to even just “learning a practical lesson” (e.g., “mad scientists shouldn’t play god” or “the dangerous monster can be defeated if we work together” or even “karate makes me powerful”).

In smaller arcs, characters will not necessarily need to experience a dramatic ego death or shift in personal paradigm or identity. They may end the story simply feeling slightly more whole or affirmed. Bigger arcs tend to speak more obviously to our deeper psyches and to the audience’s own inner experience of symbolic life. This is because their scope allows them to draw down bigger and more powerful symbolism, since they often deal with high-stakes situations that are relatively rare in day-to-day life, allowing them to offer important cathartic experiences.

Meanwhile, smaller arcs can be extremely satisfying for audiences in their ability to recreate the sort of relatable situations we all regularly encounter and work through. Major ego deaths are threshold experiences that only happen a few times throughout our lives; smaller perspective shifts, however, happen on a daily basis. The best small arcs are those that intentionally lean into the verisimilitude and reliability of daily evolution.

For Example:

The show Gilmore Girls thrives on micro arcs that bring satisfying movement to each episode without fundamentally altering the characters. Mother and daughter protagonists Lorelai and Rory are defined by strong personalities and consistent worldviews, and the series’ charm lies in watching those traits play out in different circumstances. Most episodes introduce a conflict rooted in family dynamics, town politics, or personal relationships, such as Lorelai needing to smooth things over with her parents or Rory stumbling in balancing academics with friendships. By the end of the episode, the tension is usually resolved with a small shift in outlook: someone apologizes, admits fault, or simply sees a situation from a slightly different angle.

These micro arcs don’t reinvent the characters. Lorelai doesn’t stop being witty and independent, Rory doesn’t stop being studious, their mother/grandmother Emily doesn’t stop being controlling. But the little tweaks in understanding provide the story’s sense of movement while keeping the characters familiar and dependable, which is exactly what makes viewers want to return to the town of Stars Hollow week after week.

In Gilmore Girls, Lorelai and Rory show how small character arcs—tiny shifts in perspective or relationships—can carry a story’s emotional heart. (Gilmore Girls (2000-2007), The CW.)

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Often, however, small arcs are less advantageous in bigger stories. In neglecting to pair meaty character arcs with the high stakes of plot-driven spectacles, stories often gut their very soul—theme. Theme arises directly from the interplay of external events challenging characters to change—not just on an external, practical level, but on a deep, personal level. When episodic high-tension stories fail to match their plot events with commensurate character evolution, they are not only missing out on their best potential, but also presenting an ultimately dissatisfyingly out-of-sync presentation of reality. They often ring hollow and become all-too-forgettable for the simple reason that their bluff and bluster isn’t allowed to mean anything.

For Example:

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom heightened its spectacle even further than its predecessors, escalating the stakes to include not just an island of dinosaurs but the potential weaponization and global spread of these creatures. Yet despite the apocalyptic implications, the characters’ arcs remain small and underdeveloped. Claire softens slightly from her corporate-minded pragmatism into a more openly compassionate activist, but this shift is incremental compared to the world-shattering events around her. Owen, meanwhile, remains essentially unchanged—an action hero stereotype who doesn’t evolve in any significant way.

The mismatch between the immense external conflict and the modest internal growth means the film struggles to generate any thematic depth whatsoever. Its bluff and bluster never quite land because the story neglects the deeper resonance that comes when characters’ internal journeys rise to meet extraordinary stakes.

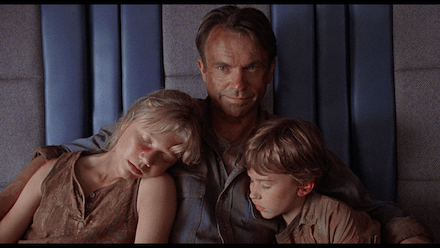

By contrast, the original Jurassic Park paired its high-stakes dinosaur spectacle with a heartfelt internal arc: Alan Grant’s begrudging discomfort with children gradually transforms into protectiveness and affection as the high stakes demand he bond with the two children in his care, giving the story an emotional anchor that elevates its thrills into resonance.

Alan Grant’s quiet transformation in Jurassic Park shows how small arcs can give big stories their emotional heart. (Jurassic Park (1993), Universal Pictures.)

Flat Arcs and How Characters Stay True While Driving the StoryA final consideration for your story is the Flat Arc. The Flat Arc represents, basically, the next level a character may reach after a Change Arc. The Flat Arc is a story about a character who already “gets” the Truth. However, because stories still require the engine of internal change in order to generate meaning, these stories will still feature characters who change. The difference is that here, the Flat Arc protagonist acts as an Impact Character who represents the thematic Truth and inspires Change Arcs in the supporting characters—whether those arcs are large or small.

So much can be done with a Flat Arc character. Not only can they be used to create a stable axis for an ongoing series, in which potentially everything changes except the protagonist—they can also develop tremendous complexities in their own right. The most important thing to remember about Flat Arc characters is that just because they’ve figured out the thematic Truth at the center of the story, this doesn’t mean they understand all truths—or even any other truth. In short, they can be wonderfully limited and flawed characters while still acting as catalysts for the changes that need to happen in the external story world.

For Example:

Sherlock Holmes remains firmly grounded in the series’ central Truth that rational observation and logic can uncover reality. He doesn’t need to undergo a sweeping personal transformation from story to story; instead, he acts as the stable axis around which the mystery turns. This doesn’t mean Holmes is perfect or even well-balanced. His arrogance, addiction, and emotional blind spots remind us that a Flat Arc character can be deeply limited.

What makes him fascinating is precisely this tension: he embodies the thematic Truth that reason exposes deception, but he does not grasp (or refuses to engage with) many other truths, such as those of empathy, humility, or human connection. His steadfastness allows him to be a catalyst for the story’s external resolution, while his flaws keep him vivid and complex, preventing him from collapsing into a lifeless stereotype.

Sherlock Holmes demonstrates a Flat Arc: he already embodies the thematic Truth of reason and logic, shaping the story world without undergoing major change himself. (Sherlock Holmes (2009), Warner Bros.)

This makes Flat Arc characters excellent choices for many types of series, especially episodic series, in which the central premise remains the same (e.g., a detective solving a mystery) while the plot details change (e.g., new murderer and new suspects in each installment). Flat Arc characters tend to be particularly archetypal. In their unchangingness, they represent a single symbolic catalyst. While this can create striking depth, it can also become stereotypical and, yes, flat very quickly.

Used with discretion and awareness, Flat Arc characters stand as extremely powerful and inspirational (or cautionary) figures. Fundamentally, they represent characters who are a step ahead on the path. They are characters who have emerged from the comparative ignorance of a previous Positive Change Arc (even if it is never referenced) in order to embody a particular Truth (i.e., a slightly more expanded perspective than that of the surrounding story world). Their seeming simplicity can actually make them quite tricky to write well, but when executed skillfully, they provide all kinds of versatility for the author.

For Example:

Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird is a quintessential example of a Flat Arc character used with tremendous discretion and power. He has already moved beyond the ignorance of believing society’s Lie—that prejudice and inequality are acceptable—and now lives firmly in the Truth of justice, empathy, and human dignity. Because he stands a step ahead of the rest of Maycomb, his role is not to transform internally but to act as a moral catalyst, challenging the community and inspiring his daughter Scout.

His apparent simplicity (i.e., he is calm, principled, unwavering) makes him seem almost mythological, which is precisely what gives him his symbolic force. He embodies a Truth others must grapple with, and the drama arises from how his world reacts to his steadfastness rather than from any change within him. Written well, such Flat Arc characters can serve as luminous figures, offering readers a vision of what it looks like to live by a deeper Truth even when it comes at great personal cost.

Atticus Finch shows how Flat Arc characters embody moral truth and inspire growth in others without needing to transform themselves. (To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Universal Pictures.)

Whether you’re writing a sweeping epic or a cozy slice-of-life, remember: the heartbeat of your story lives in the character arcs. Big arcs grip us because they reflect the rare, seismic changes of real life, while small arcs and Flat Arcs resonate because they reflect the daily steps of growth, resistance, and steadfastness we all experience day to day. When writers understand the spectrum of arcs available to them, they gain the power to craft stories that feel meaningful and true while also choosing the approach that makes the most sense for any particular story.

In SummaryCharacter arcs exist on a spectrum—from dramatic transformations that shatter identity to small but satisfying shifts in perspective,to Flat Arcs that anchor the story’s thematic Truth. Each option brings different opportunities and challenges, and the best choice depends on the kind of story you’re telling.

Key TakeawaysBig Arcs: Redefine a character’s worldview through dramatic conflict between Lie and Truth.Small Arcs: Mirror everyday perspective shifts that create relatability and subtle growth.Flat Arcs: Provide a stable axis through embodied experience that inspires change in others.Balance matters: The scale of the arc should align with the scale of the story’s stakes to create resonance and theme.Want More?Need a fast, reliable roadmap for mapping out your characters’ journeys?

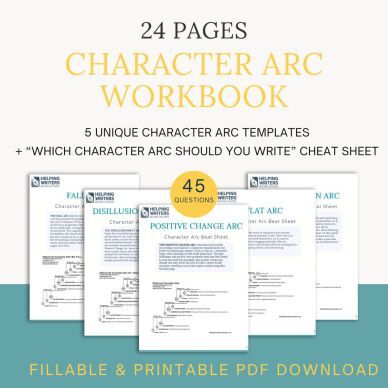

Check out my Character Arc Quick Guide Pack, featuring five fillable worksheets that break down the essential beats of every major arc type (Positive, Flat, Disillusionment, Fall, and Corruption). Whether you’re outlining a brand-new protagonist, testing alternate possibilities for a supporting cast, or just looking for a quick-reference checklist during revisions, I designed these worksheets to give you a streamlined way to develop arcs that work. Instantly downloadable, printable, and reusable, they’re designed to save you time while making sure your characters’ inner journeys stay just as compelling as your plot twists.  Grab the Character Arc Quick Guide Worksheets here.

Grab the Character Arc Quick Guide Worksheets here.

Plan your story with the Character Arc Workbook Quick Guide—5 templates, 45 questions, and a cheat sheet to help you choose the right arc.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What kind of character arcs do you most enjoy writing—or reading? Do you prefer the catharsis of big transformations, the relatability of small shifts, or the steadfast power of Flat Arcs? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Big vs. Small Character Arcs: Understanding the Degrees of Change in Storytelling appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.