A Tale of Two Fernandas: “Central Station”

When, at this year’s Golden Globes ceremony, Fernanda Torreswas called to the stage, I was surprised. She had just won the statuette for“best performance by a female actor in a motion picture—drama,” the cumbersometitle for a category that included such big names as Nicole Kidman, TildaSwinton, and Angelina Jolie. Torres’ film, the Brazilian I’m Still Here,meant nothing to me back then. But I began paying attention when Torresfollowed up her Golden Globes win with an Oscar nomination for Best Actress forthe same film (Mikey Madison ultimately took the prize for Anora), andwhen I learned more about her.

It’s always been rarefor actors to nab Oscar nominations (let alone wins) for films made in foreignlanguages. In 1960 Sophia Loren won her Oscar for the Italian-language TwoWomen, making her the first lead performer to ever be honored by theAcademy for a foreign language role. But Torres’ nomination was by no means afirst for Brazil nor for Latin America as a whole. Back in 1999, her ownmother, also named Fernanda, was Oscar-nominated as Best Actress for Centraldo Brasil (also known as Central Station). Fernanda Montenegro, themother of Fernanda Torres as well as film director Claudio Torres, is consideredone of Brazil’s cultural treasures. Now 95, she is still active, and evenplayed her daughter’s character—now at an advanced age—at the tail-end of I’mStill Here.

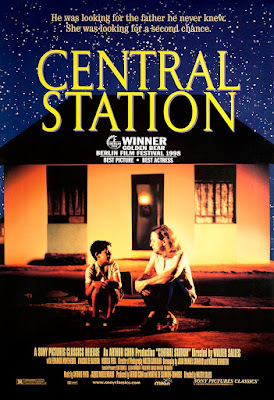

But Central Station (directed by Walter Salles, whowould later helm I’m Still Here) remains Fernanda Montenegro’s greatestinternational triumph. Since I’ve now seen—and very much admired—I’m StillHere, I was curious indeed to watch a film that shows Montenegro in all herglory. It’s hardly a glamour role, and she was almost 70 at the time, though Iwould have pegged her for a somewhat younger woman. The film begins in Rio deJaneiro’s central railway station, where someone named Dora has set up a tableto serve passersby. She’s a retired teacher, and in a country where illiteracyis rampant she offers her services writing letters for a modest fee. That’s howthe story begins: we see vivid close-ups of locals dictating the letters theywant to send—angry letters, love letters, plaintive missives to Jesus. For asmall extra charge, she’ll promise to post your letter too. What the customersdon’t know is that, after she briskly leaves the station, she’ll head for hermodest flat and stuff the unsent letters into a drawer. Or even tear them up.

But her encounter with one customer unexpectedly changeseverything. The woman shows up at Dora’s table with her young son, who’sdesperate to meet the father he’s never known. The woman herself seems to havemixed emotions about her former spouse, who’s apparently a drunk, though sheultimately admits she misses him. I won’t go into the circumstances that putDora herself suddenly in charge of the boy’s future, but the film evolves intothe duo’s long and complicated journey to a remote northern Brazilian town. Thisis ultimately one of those films, like for instance Claude Berri’s The Twoof Us, in which a crusty oldster evolves into a kindly protector for aneedy child. The growing bond between the cantankerous woman and the street-smartkid (young Vinícius de Oliveira was an airport shoeshine boy before landingthis, his film debut) is convincing, and the big nightime scene in which theylose one another in the midst of a smalltown religious festival is a small cinematicmasterpiece, leading up to a deeply poignant ending.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers