Why I Ran A Solo Race From Marathon To Athens (And What It Taught Me)

I remember exactly where I was.

Twenty years ago, I was working in Hollywood. On my lunch break, I was at Philly’s Pizza on La Cienega and Olympic, reading The 33 Strategies of War by Robert Greene. In a chapter about the “divide-and-conquer” strategy, Robert writes about the Athenians’ legendary stand against a massive Persian invasion on the plains of Marathon in 490 B.C. After the battle in Marathon, the soldiers had to immediately race back to Athens where a second Persian fleet was on its way to take the city from the sea.

“There was simply no time to rest,” Robert writes. “They ran, as fast as their feet could take them, loaded down in their heavy armor, impelled by the thought of the imminent dangers facing their families and fellow citizens…Within a matter of minutes after their arrival, the Persian fleet sailed into the bay to see a most unwelcome sight: thousands of Athenian soldiers, caked in dust and blood, standing shoulder to shoulder to fight the landing. The Persians rode at anchor for a few hours, then headed out to sea, returning home. Athens was saved.”

Had the tired, dusty soldiers not run from Marathon to Athens, Robert writes, “history would have been altered irrevocably,” as the Persians, in conquering Greece, would have crushed the Athenians’ nascent democratic experiment that went on to shape the western world. Perhaps there would be no such thing as Western civilization.

I had previously read about the Battle of Marathon in Herodotus’ Histories but this was so much more vivid, I actually understood what was happening and why it mattered. There in the pizza shop, I was struck by the way the same historical event could be transformed in the hands of a different storyteller. I remember being struck in particular by Robert’s line, “caked in dust and blood.”

In any case, I emailed Robert and asked what he read when he was researching this famous event. He told me his sources, which included a book called The Greco-Persian Wars by Peter Green. I immediately ordered it on Amazon, and a few days later (Amazon was a little slower then), I began to read it on my lunch break.

The screenwriter and director Brian Koppelman (Billions, Rounders, Ocean’s Thirteen) talks about “The Moment”—the critical moment in every aspiring artist’s life, when the craft they have long elevated as magic or beyond their grasp suddenly becomes a bit more comprehensible.

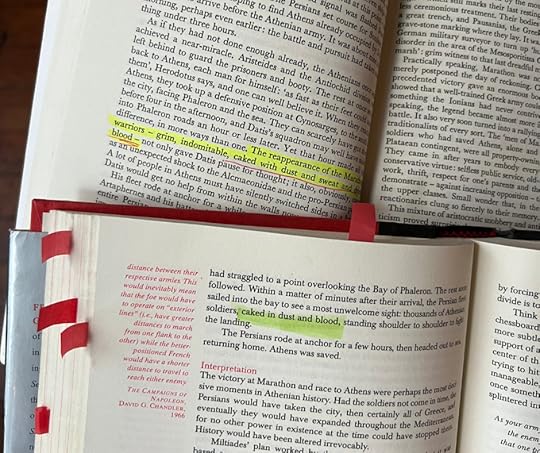

My moment happened about forty pages into The Greco-Persian Wars, where Peter Green writes, “The reappearance of the Marathon warriors — grim, indomitable, caked with dust and sweat and dried blood — not only gave Datis pause for thought; it also, obviously, came as an unexpected shock to the Alcmaeonidae and the pro-Persian party.” It was here that I realized: Oh, this is how it works. This is what a researcher, a writer, a storyteller does: they read a collection of books on the same event, filtering the many details through their own lens based on their own tastes, which they then shape into their own style to make something new.

The passage from The Greco-Persian Wars (top) that Robert Greene used in The 33 Strategies of War (bottom).

It was a breakthrough moment for me. A little peek behind the curtain of the previously intimidating craft that I was drawn towards. A realization that on the other side of the books I admire and love is just another human being doing a job. And I’m a human being too, so maybe if I work hard enough, I can write books too.

Now, there was nothing in either of the Green(e) books about the fact that one could still go to Greece and run the course the Athenian soldiers, caked in dust and blood, ran from Marathon to Athens. But not long after, I read what became another all-time favorite book, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which Haruki Murakami writes about running “the original marathon course” all alone, not as part of “an official race.”

Re-reading “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running”

I had been a runner for a long time, and the one thing you get asked all the time as a runner is, “Are you training for a marathon?” My answer was always, “No, this is the marathon.” That is, the day-to-dayness, the doing it for no reason other than because, is the real challenge I’m tackling.

That’s how I thought about running basically from the moment I left organized sports as a kid. It’s, as Murakami talks about in one of my favorite passages in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, both exercise and a metaphor. “Running day after day,” he writes, “bit by bit I raise the bar, and by clearing each level I elevate myself. At least that’s why I’ve put in the effort day after day: to raise my own level. I’m no great runner, by any means. I’m at an ordinary—or perhaps more like mediocre—level. But that’s not the point. The point is whether or not I improved over yesterday. In long-distance running the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be.”

Combined with my longtime fascination with the way that ancient, original Marathon tipped the balance of history, Murakami’s quiet account of running it alone—not for a medal or a crowd, but simply to raise his own level—planted the idea of one day running it myself. It had been sitting in my mind for some fifteen years when my wife and I started planning a trip to Greece with our two boys this past summer.

Along with bringing to life the places I’ve been reading about for years and years—Olympia, Ithaca, Delphi, Thermopylae, Mt. Olympus and more—finally, I was going to try to run from Marathon to Athens.

After looking at a lot of the marathon training regimens out there, I didn’t have to change much. (Which was my point all along: If you stay ready, you don’t have to get ready). The only real shift was being more deliberate than usual about running in as many different environments and conditions as possible.

I went for long runs up switchbacks in Palm Springs, along the Santa Ana River in California, on mountain trails in Utah (where I was warned to look out for a very protective mother moose and her two calves) and as I often do, around Lady Bird Lake in Austin, and through the eerie elephant graveyard of the burned-out forest of Bastrop State Park.

Training in Sundance, UT

I ran in 105-degree heat. I ran on steep inclines. I ran before dawn, at altitude, on cement, gravel, sand. And once we got to Greece, I trained at the Acropolis. I trained in Ithaca. I trained running up Mount Olympus. I went on hikes with my family. I swam in the Aegean Sea. As Epictetus says, the goal when we come up against adversity—as I knew I often would during the long, hot, solitary run from Marathon to Athens—is to be able to say, “This is what I’ve trained for, for this is my discipline.”

Training in Greece

Swimming in Greece

At 6:51 a.m. on July 13, I stood at the starting point of the original Marathon route. I wasn’t nervous. And I was nervous about not being nervous. But the stillness came from training. I had done the work.

It was not the prettiest of courses, and I was the only one out there. I ran on sidewalks. I ran on the shoulder of busy roads. I ran along shopping centers and autobody shops. I ran on the side of a freeway and through underpasses. There was a brief period where you had a peek at the ocean, but most of it was industrial and gritty. It was entirely asphalt excepting a few brief moments of rocks by the side of the road.

Three and a half miles in, I came to the ruins Murakami writes about in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running,

“As those who watched the TV broadcast of the marathon at the Athens Olympics are aware, after the runners leave Marathon, at one point they go off on a side road to the left, run past some less-than-distinguished ruins, and then return to the main road.”

It is perhaps the only part of the book I disagree with. I wouldn’t say they are “less-than-distinguished” ruins. I would say they are some of the most impressive and meaningful ruins in the entire world. I was incredibly struck by them. In particular, I was struck by a giant mound surrounded by trees—the burial mound of the 192 Athenians who died at Marathon, to whom we owe basically all of Western civilization. Theirs was not to reason why, Tennyson famously wrote about another group of soldiers on an impossible mission. Theirs was but to do and die. Or as the Spartan monument says, tell a stranger passing by that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

In part, Stoicism itself, the philosophy that I am lucky enough to write about, is rooted in the epic heroism of those Athenian soldiers. Not just because they saved Greek civilization, but because they were held up by the early Stoics as models of the four virtues—courage, discipline, justice, and wisdom—that they themselves strived to live up to. The Stoa Poikile—literally the “Painted Porch”—where Stoicism was founded, earned its name not because the porch itself was painted, but because a series of famous paintings lined its walls.

We’re told by ancient historians that of all the “great deeds” depicted in the Stoa Poikile, none was more prominently displayed than the Battle of Marathon. One 1st-century B.C. writer writes that the Athenian general Miltiades “was given a special honor…When the battle of Marathon was painted, his picture was placed first among the ten generals, and he was shown urging on his men and joining battle.” Again, this wasn’t just a 26-odd-mile run for those soldiers sweltering under armor, caked in dust and blood. It was an existential fight. The fate of Greece—and with it, the future of the world—was on the line. The sheer bravery and strength of those Athenians, covering the very distance I was now running, powered me through the next seven or eight miles.

A little over halfway in, I was still feeling good. And I found myself thinking about what the Stoics say about undergoing a hard winter’s training: we train, we do hard things, we challenge ourselves—physically, mentally, spiritually—so that when life throws its own challenges at us, we have something to draw on. We have proof. Evidence that we are someone who can do hard things. Someone who can keep going. Someone who has done the training.

25 km into the run

But then I entered what Courtney Dauwalter, one of the great ultramarathoners of all time, calls the “pain cave”—where you hit the edge of your mental and physical limits. When I interviewed Courtney on the Daily Stoic podcast, she talked about how she gets excited when she reaches her pain cave during a long run. Instead of thinking about the pain and discomfort, she thinks about exploring how far back the cave goes, what’s inside it, how she might chip away at the back wall to push it just a little farther away for next time.

With about 3 miles left, I was as deep in that cave as I think I’ve ever been as a runner. It was 90 degrees now and it didn’t matter how much water I drank, I could not get hydrated. I had trouble reading the map on my phone, my brain basically wasn’t working. It’s clear afterwards that I had sunstroke or was in the early stages of it. Whatever time I was hoping for fell away, and it was really just whether I was going to continue or not. Epictetus talked about only entering competitions where winning is up to you. I tried to remind myself that I was not doing this for an outcome. There was no time or goal I was chasing. Doing this thing I had never done before, elevating myself, raising my own level—that was the real competition. And winning it was up to me. As long as I don’t quit, I thought, I’ll probably make it to the other side.

I would have loved to have finished stronger, but I ran into a complete wall. There wasn’t much I could do—physically or mentally. Both my mind and body were begging to quit. I thought of the Kipling lines in If—

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”

I held on. I didn’t quit. I gutted it out. I finished.

After finishing, I was wrecked. The story about Pheidippides is that when he finished the journey back to Athens, he delivered his message and then immediately died. I didn’t exactly do that, but I did throw up in one of the oldest and most beautiful stadiums in the world. I threw up before the long drive back to my hotel. And when I got to the hotel, I threw up several more times. I couldn’t keep down even water.

In the days after the run, once I was somewhat back in command of my faculties, I thought about what I could have done better. I could have managed the nutrition side of things better. I could have started a little bit earlier so that I could have finished before it got as hot as it did on the final miles.

In a word, I could have been wiser. Obviously, discipline is incredibly important, but without the virtue of wisdom—understanding the right place to apply that discipline and how to support that discipline—you can get yourself in some very rough spots. And so discipline is something we have to moderate with wisdom. The wisdom of, What is the best plan? What is the best nutrition? How do you not get wrecked by the heat? How do you take care of your body?

Seneca talked about how the only people he pitied were those who hadn’t been through adversity or experienced difficulty. Because they will never know what they’re capable of.

What I took most of all from running the Marathon is that I am a person who is capable of doing hard things. I know that because I did a hard fucking thing.

And I take that with me.