Writing Better Character Conflicts With the 5 Conflict Management Styles

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, I just wanted to let you know that this weekend, I’m excited to be sharing a presentation at the WorldShift: The Speculative Fiction Writers’ Summit 2025. This is a free, 4-day online event packed with workshops on character, worldbuilding, plotting, publishing, and more from 30+ writing experts. Whether you write speculative fiction or not, you’ll walk away with tools you can use in any story. You can grab your free ticket here: Join the Summit.

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, I just wanted to let you know that this weekend, I’m excited to be sharing a presentation at the WorldShift: The Speculative Fiction Writers’ Summit 2025. This is a free, 4-day online event packed with workshops on character, worldbuilding, plotting, publishing, and more from 30+ writing experts. Whether you write speculative fiction or not, you’ll walk away with tools you can use in any story. You can grab your free ticket here: Join the Summit.

***

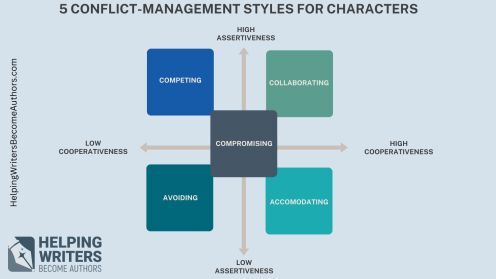

In fiction, every clash between characters comes down to a conflict management style. This is true whether you’re writing a heated argument or a quiet standoff. In real life, psychologists group these into five main approaches: competing, collaborating, compromising, accommodating, and avoiding. Understanding how each works can help you write richer, more realistic character conflicts.

It is a common axiom in the writing world that conflict drives story. Although the simplicity of this advice is necessarily limited, what it means is that plot is created from a series catalysts that cause characters to respond. Basically: cause and effect.

This is what then creates the chain of story events (aka, scenes) that engenders the larger story. At its simplest, story conflict is nothing more or less than some kind of obstacle interfering with a character’s forward progression. That said, the word “conflict” itself does tend to most readily connote interpersonal conflict—whether in the form of a fistfight or a passive-aggressive argument. Indeed, most people find this aspect of conflict to be the most obviously entertaining and useful for plot, since it tends to inherently combine all three of a story’s major engines: plot, theme, and character.

This means that much of what writers need to know about conflict in general comes down to character conflicts. The more nuanced your characterizations, the more interesting the conflict will be and the more realistic and compelling your characters will be.

So how do you create nuanced character conflict?

One way is to study and understand conflict management styles. If you can figure out which conflict management styles best fit your characters, you not only have the opportunity to create instantaneously complex relationship dynamics (since every character’s approach to conflict will be different), but also conflict that naturally arises from the management styles themselves (e.g., characters with opposing styles can sometimes spark conflict just because they clash with each other’s approaches).

In This Article:Take the Test: What Are the 5 Conflict Management Styles?Using the 5 Conflict Management Styles to Build Character ConflictThe Competing Style: High-Stakes ShowdownsThe Collaborating Style: Win-Win SolutionsThe Compromising Style: Meeting in the MiddleThe Accommodating Style: The Peacemaker’s PathThe Avoiding Style: Delaying the BattleTips for Mixing Conflict Styles in Your StoryTake the Test: What Are the 5 Conflict Management Styles?The idea of five distinct conflict management styles comes from the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI), developed in the early 1970s by psychologists Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann. Originally designed for workplace and organizational settings, the model maps how people handle conflict along two dimensions: how a person pursues one’s own goals (i.e., a spectrum of unassertiveness and assertiveness) and how one considers others’ goals (i.e., a spectrum of uncooperativeness to cooperativeness). From there, they used these two axes to map five core approaches to conflict: competing, collaborating, compromising, accommodating, and avoiding.

To discover which style best fits your characters (and yourself!), you can purchase the official test here. Below is a short version that can get you started by giving you the general idea:

Character Conflict Style QuizDiscover how your characters naturally handle disagreements, tension, and power struggles. Start by choosing a single character you want to assess. For each statement below, imagine how this character would respond in a variety of situations (e.g., with friends, rivals, strangers, etc.).

Rate each statement on a scale of 1–5:

1 = Strongly Disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Neutral / Sometimes True

4 = Agree

5 = Strongly Agree

At the end, follow the scoring guide to discover your character’s dominant conflict style(s).

The StatementsMy character pushes hard for his/her own way, even if it risks upsetting others.My character seeks solutions that work for everyone involved in the disagreement.My character will give up part of what he/she wants if it helps resolve the conflict.My character often lets others have their way to keep the peace.My character avoids bringing up issues unless there’s no other choice.My character enjoys finding creative solutions in which everyone feels satisfied.My character is willing to settle halfway if it ends the argument quickly.My character puts the other person’s needs first when harmony matters most.My character changes the subject or withdraws to avoid escalation.My character insists on his/her own position, believing he/she’s right.ScoringAdd the scores for each style category:

Competing = Q1 + Q10Collaborating = Q2 + Q6Compromising = Q3 + Q7Accommodating = Q4 + Q8Avoiding = Q5 + Q9Highest Score → This is your character’s dominant style in conflict.

Close Second(s) → These could be secondary style(s) your character may use in certain situations.

Lowest Score(s) → These are the styles your character is least likely to use.

Use the dominant style to shape your characters’ dialogue, body language, and choices in tense scenes. From there, you can play with your story’s conflict by putting your characters in situations that force them into their weakest styles. Not only does this usually create more conflict, but it’s great for growth arcs and plot twists. Also, look for ways to combine different styles in ensemble casts to create natural friction between characters.

Understanding conflict management styles for your characters can provide a solid foundation that influences many aspects of your story. This lays the groundwork for realistic personalities, while also contributing to how you manage each scene’s tension, pacing, and tone. It will influence how character relationships play out, and—since this is usually the heart of any story—from there it can end up creating the plot all by itself.

If you realize any one character lacks a strong conflict style and/or many of your characters share the same style, you can easily troubleshoot for a stronger narrative by mixing things up or strengthening the accuracy and consistency of how a particular conflict style is showing up in your story.

Using the 5 Styles Conflict Management Styles to Build Character ConflictLet’s take a deeper look at each of the five styles and how each one might show up in your fiction.

5 Conflict Management Styles for Writers Graph (click for larger view).

1. The Competing Style: High-Stakes ShowdownsCharacters with a Competing style go all in to get what they want. They score high in both assertiveness and uncooperativeness, which means they tend to prioritize victory over relationships. This can be a great way to raise the stakes, since it creates scenarios with clear winners and losers.

Although these characters often come across as selfish, they can also be excellent leaders since they are ultimately all about efficiency. Their focus is entirely on getting results, which can actually be on behalf of someone else (i.e., protecting or providing for the group) even if relationships are often not factors in the decision making.

For Example:

Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada relentlessly pushes her own agendas, regardless of how it impacts others. When she demands Andrea obtain an unpublished Harry Potter manuscript for her twins, Miranda exerts total control, making it clear her needs come before anyone else’s.

The Devil Wears Prada (2006), 20th Century Fox

Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick obsessively pursues his own goal (killing the whale), even at the cost of his crew’s safety. He rallies the crew to join his hunt for Moby-Dick, overriding the ship’s original mission and dismissing the first mate Starbuck’s concerns.

When two characters team up to find a solution that works for everyone, they’re Collaborating. Unlike the Competing style, the Collaborating style can often serve to strengthen connections even while highlighting differences. Like Competitors, Collaborators score high in assertiveness. They’re there to get the job done, but because they also score high in cooperativeness, they wish to do so in a way that doesn’t clearly define themselves as winners and everyone else as losers.

These characters make great leaders, although usually more heart-based than the head-based Competitors. Sometimes their downfall can be trying to make situations work for everyone when that isn’t possible or desirable (which can ironically cause everyone to “lose”).

For Example:

As she becomes a leader, Moana works to find solutions that honor her people’s traditions while also solving their urgent needs. When she realizes the antagonist is actually the goddess Te Fiti, Moana does not seek to defeat her, but rather restores her heart, resolving the conflict in a way that benefits everyone.

Moana (2016), Walt Disney Pictures.

Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird strives to seek truth and fairness by balancing empathy with justice and involving others in the moral conversation. During his courtroom defense of Tom Robinson, he appeals to the jury’s conscience and shared values in an attempt to gain a resolution that serves both justice and his community’s moral integrity.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Universal Pictures.

3. The Compromising Style: Meeting in the MiddleThis style desires both sides to give a little and meet in the middle. Compromisers tend to create a partial resolution that still leaves some tension in play. Compromisers ride the middle of both axes—assertiveness and cooperation—landing somewhere betwixt and between. Because they lack as much assertiveness as Competitors and Collaborators, they tend to fill leadership roles only reluctantly and in the absence of someone more decisive. This isn’t necessarily because the more decisive types are better leaders, but because those types can sometimes fill the role faster, while the Compromising type is still examining all the options.

The Compromising style can often lend itself to indecision. Because their greatest desire is for everyone to be happy, they can get stuck in pursuit of an impossible ideal. They can be frustrating to both assertive types, but offer valuable and necessary perspectives.

For Example:

Marty McFly in Back to the Future consistently seeks middle-ground solutions to avoid outright confrontation, like persuading George to stand up to Biff so he doesn’t have to directly fight Biff himself, or finding a way to get the time machine running without demanding perfection from Doc.

Back to the Future (1985), Universal Pictures.

Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games often negotiates partial agreements with allies (like Peeta or Haymitch) to survive, while still holding to her values. Although she will fight if pushed (indicating a secondary conflict style), she generally prefers to find workaround solutions.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

4. The Accommodating Style: Seeking PeaceSometimes a character will give in to keep the peace, a choice that can alternatively reveal loyalty, fear, or quiet acts of self-sacrifice. This conflict style scores low in assertiveness and high in cooperativeness. Although this style often lends itself to characters who can get run over by more assertive types, it also represents the most empathetic of the five. This is usually a person who is highly tuned in to others.

However, their conflict aversion can make it difficult for them to get what they want or to pursue (or sometimes even acknowledge) their own desires. If they don’t have a strong secondary style to help them out, they can (ironically) struggle to create enough conflict to drive the plot.

For Example:

Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings shows Accommodating tendencies in his dedication to putting Frodo’s needs and safety above his own desires, even when it’s hard, such as on Mt. Doom when he gives Frodo the last of their water instead of taking it himself, prioritizing Frodo’s needs over his own survival. However, Sam also shows a strong secondary Competitive style, especially when confronting Gollum.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

Beth March in Little Women consistently yields to her sisters’ wishes in order to maintain family harmony, even at personal cost. For instance, when Meg is invited to a party, Beth encourages her to go even though it means Beth will left be alone.

Little Women (1994), Columbia Pictures.

5. The Avoiding Style: Delaying the BattleFinally, instead of facing the issue, a character might dodge the conflict entirely. Although this can totally deflate a scene’s conflict, it can also lend itself to subtextual passive-aggression as the tension builds in the silence and unresolved emotions linger. Notably, although this type scores low in assertiveness, it scores high in uncooperativeness.

This style often lends itself to loner characters who prefer to go their own way rather than engage with others. It is separate from the Accommodating style in that it is more concerned with protecting itself than placating others. The true Avoidant style will also do almost anything to avoid conflict. It would rather slip away (either physically or by disassociation) than bond or fight in order to end the dispute.

For Example:

Christopher McCandless in Into the Wild consistently sidesteps the deep conflict of his strained family relationships, instead physically removing himself by leaving home and embarking on a solo journey into the wilderness. His avoidance defines not just isolated moments, but his entire approach to life’s tensions.

Into the Wild (2007), Paramount Vantage

Bruce Banner in The Avengers keeps a low profile in Calcutta, tending to patients and dodging any situation that might trigger his transformation. His alter-ego, the Hulk, of course, displays the opposite conflict style of Competitor.

The Incredibles (2004), Walt Disney Pictures.

Tips for Mixing Conflict Styles in Your StoryAlthough most characters will demonstrate a primary conflict style, this doesn’t mean they can’t utilize secondary tactics as well. Usually, secondary tactics will represent a less well-developed (and therefore less “mature”) approach that kicks in when the primary style proves counter-productive.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

You can use conflict styles as a central fulcrum in creating a character arc. For example, a character who relies exclusively on a Competing style might have to learn how to become less aggressive and more Cooperative. Likewise, as in Into the Wild, your story could focus on the dangers of taking any one conflict style to a tragic extreme.

One of the single best ways to utilize conflict styles in your story is to focus on the interplay between how the styles show up in different characters.

For Example:

Two Accomodating characters will probably cancel each other out, creating a scene that lacks conflict (and probably nobody getting what they want either).Two Competitive characters will be entertaining, but unless one of them arcs otherwise, their story will always end with clear winners and losers.Competitive and Collaborative leaders can create interesting stories that start with sparks and end with mutual growth.Compromising characters can often struggle in confronting other types, but offer both balanced perspectives and room for growth.With deep roots in psychology, conflict management styles make for powerful storytelling tools. By giving each character a clear, consistent approach to conflict, you can create authentic tension, natural relationship dynamics, and plot turns that feel inevitable. You may want to see your characters locking horns in a showdown or finding creative win-win solutions or slipping quietly out the back door. Whatever the case, the way they handle conflict will shape everything from pacing to theme. Mastering these five styles can help you write stories that feel more real, more layered, and far more compelling.

In SummaryThe five conflict management styles—Competing, Collaborating, Compromising, Accommodating, and Avoiding—offer writers a structured way to design believable interpersonal conflict. Each style is defined by how characters balance assertiveness (pursuing their own goals) and cooperativeness (considering others’ goals). Assigning conflict styles to characters adds depth, realism, and tension to your scenes and relationships. Going further, to mix different styles in your cast can then naturally generate friction and plot momentum. You can even shift a character’s style over time to create satisfying character arcs.

Key TakeawaysConflict drives story. Knowing your characters’ conflict styles makes that conflict richer and more organic.Different styles = different sparks. Pairing contrasting styles creates built-in tension, while matching styles can either cancel conflict or amplify it.Extreme reliance on one style can be a flaw that drives an arc or downfall.Use the Character Conflict Style Quiz to quickly identify how your characters approach disagreements.Incorporating real-world psychology models into fiction can boost authenticity and reader engagement.Want More?

Creating Character Arcs Workbook

If you’d like to take your character development even further, check out my Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Packed with guided exercises, prompts, and structure templates, it will help you chart your characters’ journeys from start to finish. It covers Positive Change Arcs, Flat Arcs, and Negative Change Arcs. Learn how to weave plot and character together seamlessly so every scene feels purposeful and emotionally resonant. It’s available in e-book and paperback.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Which of your characters has the most clearly defined conflict management style, and how has it shaped relationships or the plot? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Writing Better Character Conflicts With the 5 Conflict Management Styles appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.