Everything (And I Really Mean Everything) Is A Chance To Do This

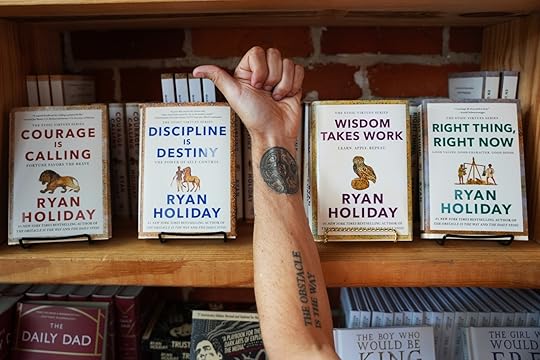

Get the limited edition collector’s set of my series on The Stoic Virtues.

I think people get it wrong.

I know I did.

When the Stoics say that the obstacle is the way, that there’s an opportunity in every obstacle, most of us take that to mean there’s some way to turn adversity into advantage.

We think of entrepreneurs pivoting during a downturn and building a billion-dollar business. We think of an investor buying back their own stock or taking advantage of being underestimated by their competitors. We think of a general using the bad weather as cover. We think of an athlete coming back stronger after an injury. We think of some rejected artist going independent and building their own label.

That’s how I was thinking about obstacles and opportunities when I wrote The Obstacle is the Way in my twenties. The simplest idea at the center of the book is that there are hidden advantages in every problem, that businesses and teams and people can take seemingly impossible situations and triumph over them. “Hard times can be softened,” Seneca writes in one of his essays, “tight squeezes widened, and heavy loads made lighter for those who can apply the right pressure.”

But what I’ve come to understand in the intervening years is that the Stoics were getting at something more profound than the fact that every downside can be flipped into some kind of advantage or transformed into a success story.

They had to.

Because it would be insane (and insulting) to say that terminal cancer was an advantage. Was there a way for Marcus Aurelius to spring forward after he buried another one of his children? Seneca can say that hard times can be softened, but then again, he didn’t have to live like Epictetus, not just through slavery but with a crippling disability from the torture he underwent at the hands of his master.

What I’ve come to understand is that the “opportunity” the Stoics saw inside adversity, big and small, was the opportunity to practice virtue. That is, it was a chance for them to rise to meet an occasion, to do the right thing, to be magnificent or magnanimous, even when they were heartbroken, even when they were being kicked around by life, even when they were dying.

Ok, so what is virtue?

In the ancient world, virtue consisted of four key components:

Courage—bravery, fortitude, honor, sacrifice…

Temperance—discipline, self-control, moderation, composure, balance…

Justice—fairness, service, honesty, fellowship, goodness, kindness…

Wisdom—knowledge, education, truth, self-reflection, peace…

Marcus Aurelius called them the “touchstones of goodness”—guiding principles for how to act, who to be, and how to respond in any situation. And there really is no situation that we can’t use as a way to practice these virtues. Even the hardest, most tragic, most heartbreaking moments of life—a terminal diagnosis, a crippling injury, losing your livelihood, burying a loved one—can be transformed by endurance, by selflessness, by courage, by kindness, by decency.

When I interviewed Francis Ford Coppola on the Daily Stoic podcast, he shared how he’s been getting through a recent tragedy in his own life—losing his wife of 60 years. “There was a Marcus Aurelius quote that really lifted me,” he told me, “which was that ‘if you lose a loved one, honor her.’ In a sense, try to be more like her, and then she’ll live on in your actions. My wife was very good—if someone was alone or sick or something, she’d call them up and be comforting to them. And I’m not like that, you know? So I started to do that. People that I know—some guys my age who have no grandchildren—I call them up and say, ‘Hey, how are you?’ And they are so pleased and so kind. And that’s how I keep my wife in my life.”

Beautiful. And closer to what I think it really means when we say the obstacle is the way.

I’ve tried to apply this formula practically in my business and creative life, but also in the difficulties I’ve faced in my life. The last decade and a half has been good to me in many ways. It’s also been…a lot. There were natural disasters, floods and fires, a freeze that broke the power grid and most of our pipes. A long drought that devastated our livestock and land. A tragic, years-long pandemic that dashed countless plans (nearly killing the independent bookstore we opened in the teeth of it). Disputes with business partners. An employee caught embezzling. Funerals and late-night phone calls with news you never want to get. The company where I made my bones went bankrupt, taking with it not just much of my résumé but what was supposed to be several years’ salary in stock options. There was a falling out with family. Hundreds of thousands of miles on the road. There was getting skunked on the bestseller lists, creative differences, daily battles with procrastination.

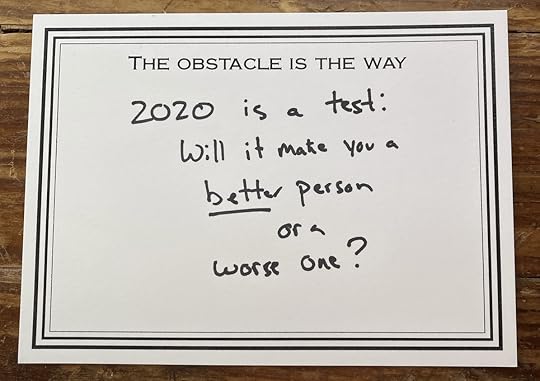

I remember in the early days of the pandemic, I wrote a note to myself along these very lines:

In spending much of that time working on the Stoic Virtues Series—four books, each on one of the cardinal virtues—I have come to more fully understand what the Stoics were getting at: LIFE IS ALWAYS DEMANDING ONE OF THESE VIRTUES FROM US. Always demanding us to be a good person despite the bad things that have happened. To do good in the world despite the bad that has befallen you. And in good times—in the face of the temptations, distractions, responsibility and obligations and obstacles that come with success and abundance—to be humble, to be disciplined, to be decent, to be generous, to hold true to your values.

When I look at the world right now, as frustrated and alarmed as I am by it, what I try to remind myself is that it’s moments like this that demand virtue from us. We don’t control so much of what’s happening. We wouldn’t choose so much of this. But here it is. What are we going to do about it? Who are we going to be inside it?

The fourth and final book in the virtue series, Wisdom Takes Work, is set to come out this fall (but is officially available now for preorder at dailystoic.com/wisdom, where we’re doing a run of preorder bonuses like signed and numbered first editions, early access to the introduction, bonus chapters, and even an invite to a philosophy dinner at my bookstore, The Painted Porch—check out all the bonuses here).

When Edward Gibbon finished The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he noted his sadness at taking “everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion.” I don’t feel exactly that way—virtue isn’t something you ever finish or take leave of—but there is something bittersweet about drawing these books to a close.

I’m better for having written them—not just as a writer, but as a person. Of course, I can already see all the things I’d do differently if I were starting over, all I’ve learned since publishing the first book in 2021. But, that’s kind of the point. To get better as you go. To learn from your time here. To put your past self to shame.

One thing I’ve noticed? I am calmer. I am quieter. I argue less. I get upset less. I admit I am wrong more often. There’s still a long way to go, but I’m proud of the progress I’ve made.

That’s how Aristotle described virtue—as a kind of craft, something one gets better at just as one would get better at any skill or profession. “We become builders by building and we become harpists by playing the harp,” he writes. “Similarly, then, we become just by doing just actions, temperate by doing temperate actions, brave by doing brave actions.”

Virtue is not something you demand of others. It’s not a standard you pass laws about or police. It’s not something we flippantly say or conflate with “success.”

It’s something you demand of yourself. It’s something you do. It’s something you use day to day, moment to moment. It’s something that steers the choices you make and the actions you take. It’s something you choose.

And every situation—big and small, positive or negative—is an opportunity to make a virtuous choice.

Will you be brave or afraid? Selfish or selfless? Strong or weak? Wise or stupid? Will you cultivate a good habit or a bad one? Courage or cowardice? The bliss of ignorance or the challenge of a new idea? Stay the same…or grow? The easy way or the right way?

Is it easy to make these choices? Of course not. That’s why I put it in the title of the new book—it takes work.

I finished the Stoic Virtues Series, but I remain committed to the work.

I hope you do the same.

With the upcoming release of Wisdom Takes Work, the team and I at Daily Stoic wanted to do something special, something we’ve never done before—a limited edition collector’s set of all four books in the Stoic Virtues Series. Each set is signed and numbered with a unique title page identifying them as part of the only printing of this series. I’m also throwing in one of the notecards I used to help me write the series (learn more about my notecard system here). There’s a limited run of these, so check them out here today.