Guest Post, Polygamy: The Doctrine that Lives In Our Bones

Polygamy: The Doctrine that Lives In Our Bones

The weight of my foremothers’ pain, the doctrines that keep it alive—and the daughter I hope never has to carry it

It started with a familiar ache in my chest. I’ve felt it before- the moment polygamy shows up where I least expect it.

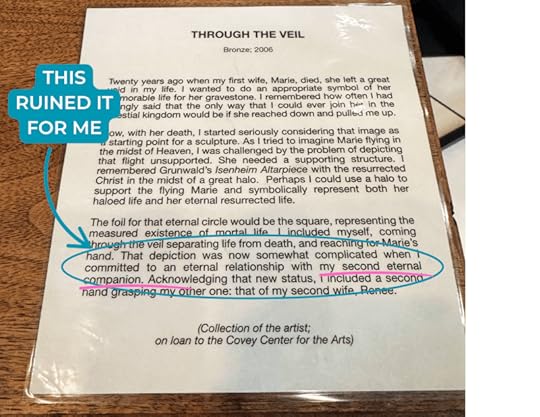

We walked past a sculpture on display at the very front entrance of the Covey Center in Provo while waiting for my 8-year-old daughter’s call time. She started reading the description out loud. At first, it sounded beautiful, something tender, honoring love and loss. I skimmed ahead of where she was reading, and suddenly the moment changed. The artist said the piece became “complicated” once he was sealed to a second eternal companion—something only men are allowed in Mormon doctrine.

My blood ran cold. That tightening in my chest rose before I could even name it. What started as a tribute had quietly turned into a celebration of a theology that has left deep scars.

It’s the same doctrine that allowed early Church leaders to coerce teenage girls—like Fanny Alger and Helen Mar Kimball—into becoming plural wives, and to use their power to claim women already in committed marriages, like Zina Huntington Jacobs.

The same doctrine that defined the lives of so many of my own ancestors—ancestors I trace through the polygamous lines in the FamilySearch app.

The same doctrine that caused my mother quiet anguish, as she struggled with the potential fate of becoming a “second wife” to a man still sealed to his ex-wife.

The same doctrine that had me, at 16 years old in Young Women’s, listing “must be older than me” right next to “priesthood holder” on my eternal companion checklist—because if he died first, maybe I’d be spared from a forced polygamous afterlife.

Even after marrying a man six years older, just like I’d hoped, the fear never left me. And in that moment, standing beside my daughter as she read the plaque, I felt it rise again.

So without missing a beat, I stopped her mid-sentence and gently pulled us away. I didn’t want her going on stage with that kind of story in her mind. I didn’t want to have the polygamy conversation in that moment. This was supposed to be a fun night. A celebration of her hard work and talent.

A few minutes later, she was off and on her way with a smile. I didn’t want to carry what I was feeling either. But the feelings lingered. They always do.

I imagined what would have happened if I hadn’t skimmed ahead of her reading out loud. How would I have explained it? She’s already been asking questions.

Why can’t girls be prophets or Church presidents?

Why couldn’t Mommy baptize her?

Why can’t she baptize people when she grows up?

I know her sharp, precocious mind won’t be okay with polygamy either. She’s already noticing the cracks— the structural, quietly accepted inequality between women and men.

Even though I no longer believe this doctrine comes from God, it still lives in my body.

The weight of it sits in my chest, coils in my stomach, and tightens in my shoulders. It’s in my nervous system, buried deep, passed down through generations of women who had no choice but to endure. My brain knows it isn’t real, but my body still flinches.

It’s embedded in the Church I grew up in.

It’s embedded in the temple, even as they try to make it less obvious.

It’s embedded in sealing practices that allow men to be sealed to multiple women, but never the other way around.

Many people I love still find deep meaning in the Church. And that’s great for them.

But for those of us who no longer believe, but are still tied to this doctrine through mixed-faith families, the trauma doesn’t just go away. Even if we’ve rejected the belief, the damage it causes is still bone deep.

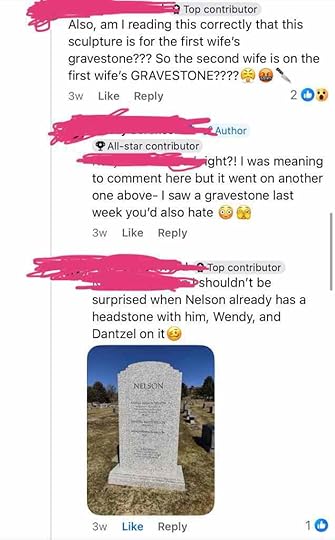

This wasn’t an isolated experience. Just a week earlier, a man in a local networking group shared what many saw as a heartwarming story about how he’d found healing after losing his wife in childbirth and remarrying just under a year later. Hundreds of comments poured in with love and support for the photo he posted: his headstone, engraved with his name and the names of two women, each sealed to him in the temple.

That’s how that woman’s resting place is portrayed, not as a person in her own right, but as the first wife in a polygamous afterlife.

In both instances, eternal polygamy wasn’t just tolerated. It was celebrated.

Let me be clear: I’m not against remarriage after loss. And I’m sure these men are good people.

To me—and to many other women—the problem is the doctrine. The idea that these marriages carry into the next life, and that we’ll be expected to become sister wives without consent.

And if the wife dies first? It doesn’t work the other way around.

I needed to talk about it. So I did.

That night, still shaken, I quickly shared a photo of the sculpture with my raw thoughts in a group of women in mixed-faith marriages (and shared about the gravestone a week before in the comments):

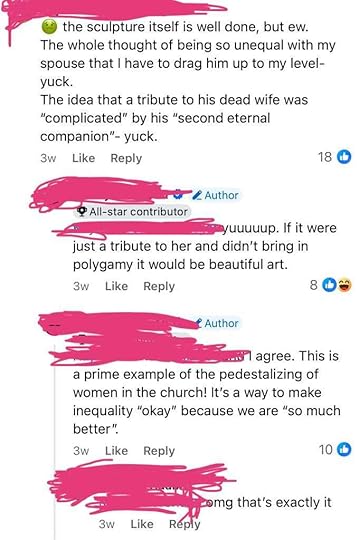

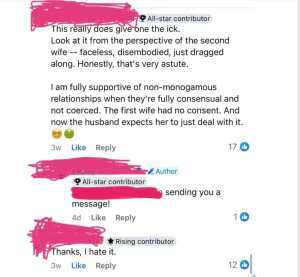

The responses were immediate and emotional:

We hurt together. We raged a little. We held space for the grief that keeps finding its way back. Because this isn’t just history—it’s now.

As Carol Lynn Pearson says, it’s the “ghost of eternal polygamy.” And unless the men who hold the power choose to confront it, this is what we’re left with. The ones most harmed by this doctrine are the ones with absolutely no power to change it. Another generation carrying trauma while waiting for men to decide whether we deserve equality.

Because the truth is, women can’t fix this.

We can write. We can cry. We can walk away—and we are, in greater numbers than ever.

But the system still belongs to men. And only they can dismantle it.

I’m not holding my breath. I’ve lost all trust in this institution and its leaders.

I wish I could just be done with it all. And yet… I’m still tethered to this doctrine through family ties.

Someday, I’ll have to talk to my daughter about the belief woven into the sculpture we saw that night.

Not because I regret staying silent in the moment. I don’t.

But because she’ll ask.

Because she’ll notice.

Because she already does.

And when that day comes, I’ll tell her the truth:

This wasn’t created by God.

This was created by men.

She doesn’t have to accept it.

She doesn’t have to carry it.

She’s allowed to feel what she feels.

And she’s not alone.

And maybe, if she never has to spend years untangling this the way I did, this is what healing across generations looks like.

The anonymous author is a mother of three and a professional writer, coach, and education expert. She draws on both personal experience and professional insight to explore the quiet complexities of faith, family, and legacy.