Conversations in Cone Bras and Candlelight

I’ve written before about my tortuous, highly emotional, and entirely unnecessary process of choosing my next read. It’s a convoluted, multidimensional selection ritual: 50% science, 50% programming, 100% trauma. At a recent business dinner, a good friend suggested I add The Second Sleep by Robert Harris to the list. Naturally, this prompted an outburst of self-indulgent moaning about the rigidity of my reading system and the sheer terror some titles inspire (Finnegans Wake and Middlemarch, I’m looking at you).

My friend then asked if I’d read “War and Peace”, to which I nodded sagely and launched into a deeply convincing soliloquy about Tolstoy, moral clarity, and the nobility of rustic labour. Which isn’t quite true. In fact, I can’t remember much about the book beyond the vague sense that I read it sometime in the previous century. To cover my tracks, I claimed to prefer Dostoevsky—a statement that was technically true, though my pretentious-ometer was by this point making an audible whine.

That night, I got home and asked myself honestly: Why do I prefer Grumpy Fyodor to Grumpy Leo?

It’s tempting to say quantity: I’ve read more Dostoevsky novels than Tolstoy’s. But that doesn’t hold—War and Peace alone could count as four books, which, as I recently checked, it literally is.

Then, I remembered another dinner.

It was also vaguely business-related: backstage, during my brief and under-documented stint as a backup dancer on Madonna’s Blond Ambition World Tour. Strangely, no one remembers my presence. Something about a cone bra stealing the spotlight.

Anyway, there we were, listening to the Big M regale us with tales of the famous people she’d encountered. The stories were glamorous, irreverent, celebratory. That is, until someone brought up nineteenth-century Russian novelists.

The room fell silent.

No one dared speak first. Then, with a dampness in her eye, she told us of the times she’d met Fyodor and Leo.

She’d dressed down for the occasion—out of respect—and met Leo Tolstoy in his candlelit study. He was barefoot, in homespun linen, naturally.

Madonna:

You live like this… on purpose?

Tolstoy (nodding):

Luxury poisons the soul. A simple life allows for truth. And you—you seem to have devoted your life to distractions.

Madonna:

I’ve devoted it to performance. Art. Self-expression. Provocation.

Tolstoy:

Provocation is not art. It is noise. True art uplifts. It speaks to the divine in man. Yours speaks to… the market.

Madonna (shrugs):

Look, I didn’t set out to be a prophet. I wanted to challenge norms. Religion. Gender roles. Power. That’s not meaningless.

Tolstoy:

To challenge is not enough. Why do you challenge? For what purpose? You use the tools of the world—fame, wealth, vanity—and believe you are above them?

Madonna:

You think I’m vain. I think I’m free. You wrote books to shake the system. I danced on stages. Same revolution. Different shoes.

Tolstoy (quietly):

You mistake visibility for truth. There is a kind of slavery in constant performance. The soul needs silence.

Madonna:

You really think someone like me can’t make meaningful art?

Tolstoy:

Anyone can. But art becomes meaningful when it forgets the self. When it loves others more than its own reflection.

Madonna:

That’s beautiful. Still… I like mirrors.

Tolstoy (smiling for the first time):

Yes. I imagine you do.

My fellow dancers and I all understood the subtext of the story immediately. How our Lady Madonna represented unapologetic self-expression and rebellion through spectacle. While Tolstoy championed humility, asceticism and moral clarity. They didn’t agree, but they listened. And in our current age, that is perhaps the most meaningful art of all.

We stopped our schoolgirl chatter when Madonna began again, this time she spoke of her meeting with Dostoevsky in a smoky corner of the Literaturnoye Kafe in St Petersburg. He in a threadbare coat, she dressed in a sleek, silken, dark dress. Her alabaster skin glowing in the candlelight.

Dostoyevsky (squinting at her):

You are not what I expected. I thought you would be louder.

Madonna (raising an eyebrow):

And I thought you’d be taller.

Dostoyevsky (smirking):

Tell me… does it tire you? The mask?

Madonna:

What mask?

Dostoyevsky:

The one that lets you command a stage. The one that shouts freedom, while hiding the terror underneath.

Madonna (leaning in and brushing her lips against his ear):

Maybe I wear masks to survive. Maybe we all do. You should know—you wrote the book on tortured selves.

Dostoyevsky:

Ah, but I sought truth through my torment. You turn torment into choreography.

Madonna:

That is art. And art isn’t always about truth. Sometimes it’s about escape. Or defiance. Or just being seen.

Dostoyevsky (nodding slowly):

Being seen. Yes. The modern disease. Everyone shouting, no one listening. But I sense… you do want to be heard, not just admired.

Madonna:

Maybe. Maybe I’m still figuring out what I want to say. But I’ve survived by saying something—anything—before anyone else could say it for me.

Dostoyevsky:

So fear drives you?

Madonna:

Fear. Anger. Hunger. Ambition. Love. I’m human, Fyodor. Same as you.

Dostoyevsky (smiling faintly):

You are more honest than many priests. That, I admire.

Madonna:

So you don’t hate me?

Dostoyevsky:

No. But you interest me. You are the Underground Woman. With exceptional cheekbones.

And, with that, she left the backstage and I never saw her again. What I liked about her second story was that unlike Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky didn’t try to correct Madonna. He sought to understand her contradictions and reflect on his own. They did not agree on what art should be, but they recognised in each other the same obsession: with freedom, with identity and with the abyss that stares back at both.

I had thought to write a very silly sketch about Madonna meeting the two great writers when I started this post, but somehow I think the sheer weight of historical reverence and unparalleled gravatas of the two of them created a vortex of profundity which no sort of satire(?) can escape, drawing everything into a strange but possibly genuine meditation on what art really is.

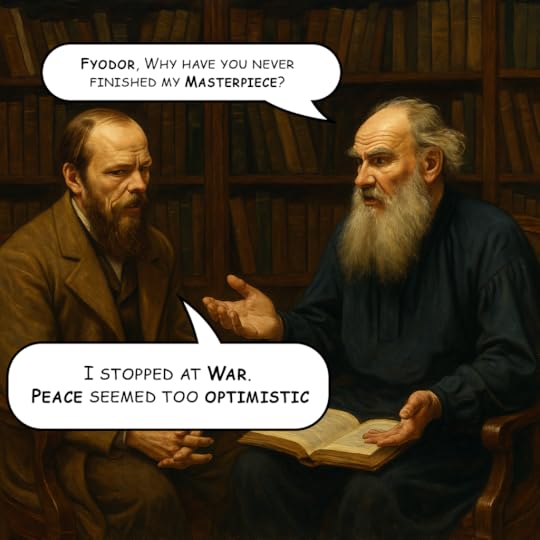

Still, I also made a little cartoon:

Sometimes, I suppose, silliness and seriousness go hand in hand. Or at least, sit at opposite ends of the same candlelit table.