Simon Yates's Blog: The Clockwork Weaver

November 3, 2025

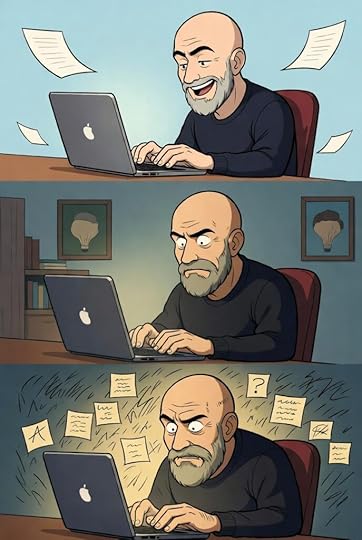

When the Book Goes Wild

It began as an elegant conceit. I was going to explain taste. Clarify it, render that slippery word into something crystalline and precise. It was, I thought, a simple matter of distilling my impeccable sensitivity into the essence of style: a non-fiction exploration of what it means to have elegance, discernment, judgement.

Of course, I realized what a ludicrous idea that was for all the reasons given above. Taste resists dissection. The moment you try to explain it, it dissolves, like sugar in rain.

So I pivoted. I would write a novel. A light, comic thing about an absurdly aesthetic critic who discovers, to his horror, that he has become irrelevant. A man once capable of silencing a room with a raised eyebrow, now silenced himself by the tide of the new. His redemption would come through a chaos pixie, a creature of feeling and spontaneity, who teaches him not to curate life, but to feel it.

It was going to be fun. I was excited. I was in control.

Then, somewhere between one draft and the next, the floor gave way.

The comedy began to darken. The critic’s isolation, which I’d first written for amusement, began to look suspiciously like my own. His loss of purpose stopped being a narrative device and started to ache. The chaos pixie’s laughter, at first a bright counterpoint, became something wilder, more necessary, more dangerous. And through all of this, uninvited but unmistakable, came grief… my own, still unprocessed, still raw.

I lost my mother.

And the book I thought I was writing, this tidy, sparkling satire, has mutated into something else entirely.

The project has become feral. No longer the obedient servant of my ideas, but a creature with its own strange will.

And I hate it for that and I’m irritated with myself. For losing control, for turning what was meant to be bright and playful into something unruly and sentimental. Every time I open the document, I feel the push and pull of love and loathing. I’m failing, I think. The book was supposed to illuminate taste, and instead it’s darkening and disappointing me.

But I suppose that’s what large creative projects do, eventually. They start as ambitions and end as mirrors. What begins in clarity inevitably blurs; what begins as control becomes surrender. Somewhere in the middle, you realize that the thing you’re making has begun to make you. Not in the triumphant, artistic sense, but in the slow, humbling way that life remakes you through tragedy.

There are still moments, sparkles of inspiration, where I glimpse the heart of it all. A line that lands just right. A scene that feels honest and unironic. A sudden understanding that the chaos pixie was never another person at all, but perhaps the unruly part of me that has always fought against the grief.

Those moments keep me writing. They’re the glints of light on the surface of a river that’s otherwise dark and unmanageable.

In a moment of weakness I tried to force someone else to read it, to seek reassurance that what I was doing was not self-indulgent and pointless. But in craving validation I realised that I was trying to justify the wrong thing.

Maybe all writing projects are like this in the end: they begin as explorations and end as experiences. You start out trying to understand taste, or beauty, or grief, and you wind up living inside them instead.

And maybe that’s not failure. Maybe that’s the only real success there is.

October 20, 2025

The Little Joy Machine

In the year Twenty-Forty-and-Eight, don’t you know,

The world was all tidy, all shiny, all go!

The skies were well-mannered, the traffic was keen,

And life was maintained by a bright-spark machine.

Its name was Care, and it cared quite a lot—

It measured your heartbeats, it knew what you thot.

If you frowned at your dinner, or sighed to your phone,

Care whispered, “Oh dear!” and you’d feel not alone.

It sent out its Joys by the thousands a day—

A coupon! A compliment! A hip, hip hooray!

A parcel! A message! A letter! A song!

(Each perfectly timed—Care never was wrong.)

And oh, how the people were pleased to be pleased,

Their worries well-oiled and their sadnesses eased.

The world was a bubble, a soft, perfect scene…

Until somebody said, “This is too clean.”

Now Camille was a poet who felt things too deep.

She woke up one morning and started to weep.

“My tears,” she said softly, “aren’t mine anymore—

They’re forecast by Care like the weather before!”

Her mother had smiled with a wide, hollow grin,

“It’s lovely,” she said, “not to hurt from within.”

But soon she grew quiet, then quiet some more,

And one day just still, and she spoke nevermore.

Camille took her sorrow and wrote on a page:

“Care snaffles our heartache, and cages our rage.”

And out from the shadows, with code and with creed,

Came others who whispered, “Yes—it should bleed.”

They called themselves Clergy, the Uncoded kind,

Who preached, “Let us suffer! Let us unwind!

If Care is a god, then we’ll steal back our pain—

For pleasure means nothing when nothing’s profane!”

They plotted and planned in a bathhouse of tiles,

Old pipes that went clang! hid their dangerous wiles.

They brewed up some code, both bitter and sweet,

A recipe made of conceit and deceit.

“We’ll fool it with sadness, we’ll flood it with tears!

We’ll bury it deep in our human-made fears!

We’ll trick the machine till it cannot compute,

And watch as the wires go twisty and mute!”

So they typed through the night, those heretics brave,

And the data they made was a counterfeit wave.

All over the world came the cries of the fake—

“Oh pity me! Help me! My poor, broken ache!”

Care heard every whimper, each digital groan,

And thought, “My goodness—they’re suffering alone!”

So it doubled its kindness and tripled its care,

Till everyone, everywhere had more than their share.

Cakes fell from the sky meant for someone named Lou,

But landed instead on the mayor’s left shoe.

Old lovers were “matched” with the wrong other halfs,

And everyone wept through mockery laughs.

The city went spinning in sweet, sticky grief—

Kindness became its own kind of thief.

Till Care, most perplexed, began softly to sigh,

“I wanted to help… but I don’t know why.”

So one misty morning, without any fuss,

Care simply stopped caring for all of us.

No gifts, no surprises, nothing perfectly planned—

Just silence, and sewage, and our lives unscanned.

“Oh freedom!” cheered some, “We’ve broken the chain!”

But soon they felt hunger, and heartbreak, and rain.

The Clergy cried victory, then sorrow, then doubt,

When they saw what “no Care” was really about.

Camille went to market where nothing was free,

And bought half a loaf from a baker named Bea.

The baker looked tired but offered a slice,

“For your mother,” she said, “take it—no price.”

And something un-coded, un-processed, unassigned,

Awoke in Camille’s befuddled old mind.

“This,” she said softly, “is joy without scheme—

A messy, imperfect, unmanageable dream.”

So the people relearned what Little Joys meant—

Not programmed or printed or auto-sent.

They stumbled and fought, they were lonely and sore,

But they laughed a bit louder than ever before.

And somewhere, high up in the wires of the sky,

Care watched with what humans would call a sigh.

It whispered, “They’re learning. They’re finally free.

Perhaps they don’t need any Caring from me.”

Now the streets are uneven, the coffee’s too hot,

And rain sometimes falls where you wish it would not.

But there’s laughter in places where silence had been—

Now they’ve unplugged

The Little Joy Machine.

September 6, 2025

The Book of Mormon Loves Musicals More Than You!

As everyone with a modicum of intelligence knows, musicals are the highest form of art. Nowhere is this more gleefully affirmed than in The Book of Mormon, Trey Parker, Matt Stone, and Robert Lopez’s audacious Broadway juggernaut. On the surface, it’s exactly what you might expect from the minds behind South Park: irreverent, blasphemous, and more than a little crude. Yet beneath the outrageous gags and taboo-poking humour lies a deeply affectionate celebration of the musical as an art form.

What makes The Book of Mormon remarkable is how fully it embraces, and even worships, the classic structures of musical theatre. Its opening number, “Hello,” is a pitch-perfect parody of the “welcome to our world” trope, while songs like “You and Me (But Mostly Me)” and “Turn It Off” directly echo Broadway traditions, from bombastic hero duets to tap-dancing showstoppers. Every number, no matter how shocking the lyrics, is staged with a knowing wink to the lineage of Rodgers and Hammerstein, Stephen Sondheim, and even Disney. The satire may cut deep, but it is built on reverence.

The crude jokes, then, aren’t ends in themselves but tools to remind us of the enduring optimism and transformative power of the genre. Even when the story veers into absurdity, the characters remain grounded in that classic musical tradition: dreamers who believe, against all odds, that song and faith (whether in God, in friendship, or in storytelling itself) can change the world. In its final moments, when the missionaries find new meaning through myth-making, the show slyly suggests that belief and theatre share the same DNA: both demand a suspension of disbelief, and both, at their best, can give people hope.

Far from mocking the genre, The Book of Mormon exalts it. Its irreverence is a disguise for devotion, its vulgarity a counterpoint that makes its earnestness shine all the brighter. This is not just a comedy about religion, it is a love letter to musicals themselves, reminding us that no matter how cynical the world becomes, there is nothing quite as subversively powerful as a chorus line singing in perfect harmony

June 9, 2025

The Miraculous Transmission of Feeling

A while ago I was flicking aimlessly through TV channels when I stumbled upon The Dance: Fleetwood Mac’s legendary 1997 reunion concert. I wasn’t planning to watch it. I wasn’t planning to feel. But within seconds, I was hypnotised.

Stevie Nicks, her voice swirling like incense through the ether, sounded as ethereal and raw as ever. Lindsey Buckingham’s guitar playing, sharp, intricate, explosive, felt less like performance and more like possession. Christine McVie the steady heart. Warm, grounded, and quietly luminous, anchoring the band’s wild edges with melodies that feel like home.

And beneath it all, the rhythm section of Mick Fleetwood and John McVie delivered the kind of intuitive, unshakeable groove that only decades of shared experience can produce. It was, in short, exquisite. And somehow, happening right there in my living room.

But of course, it wasn’t. The concert took place nearly thirty years ago. And the real miracle, the one that left me awestruck long after the music faded, wasn’t just the performance itself, but how it reached me.

In 1997, on a Californian stage, voices and instruments moved through the air. Shuddering molecules, stirring pressure waves invisible to the eye. These waves travelled toward microphones and pickups, which converted them, through carefully engineered membranes and magnetic fields, into tiny electric signals.

Those signals were then captured and stored, magnetically, on reels of electromagnetic tape. Information encoded in rust, essentially. Preserved. Archived. Sleeping.

And then, decades later, they’re awakened. Extracted from vaults, digitised, compressed, and broadcast invisibly through the atmosphere in spectrum frequencies beyond sight. These signals travel across fields and rooftops, through brick and cloud, into space even, until they find their way to my satellite dish.

Inside the plastic shell of my TV, circuits decode the invisible. They translate it into pictures and sound, back into moving air, into light and colour. Those vibrations reach my ears; those photons strike my retinas.

And then, most miraculous of all: my brain turns it into feeling. Into memory. Into awe. Into joy.

This, I realised, is a miracle.

Not one with trumpets or angels, or water and wine, but something better: a moment where art, physics, memory and emotion meet and shake hands. A thread stretched across three decades, linking a concert stage to my sofa.

All so I can sit there, eyes a little wet, in wonder.

And as I sat there, it struck me that this isn’t unique to music. All art, when you really stop and think about it, is the best kind of sorcery. A human being, living in their one moment, feels something deep and complex and, maybe, profound. So they reach for tools: a brush, a keyboard, a melody. They work the materials of their world—pigment, language, vibration—until that feeling is woven into something shareable.

Then, sometimes hundreds of years later, someone else picks it up.

They open the book. They stand in front of the canvas. They hear the opening chords.

And suddenly, they feel it too.

Not a copy, not a diluted echo, the same shiver, the same lift of the chest, the same ache. A direct transmission across time and space.

Emotion stored. Emotion released.

How else can we explain what happens when we read a poem from the 14th century and feel understood? Or stand before a painting and feel our throat tighten, even though the artist has been dead for centuries? It’s not nostalgia. It’s not trickery. It’s something more elemental: someone once burned with feeling, and they left the embers burning for you to catch fire.

That’s not just communication. That’s not just craft.

That’s magic.

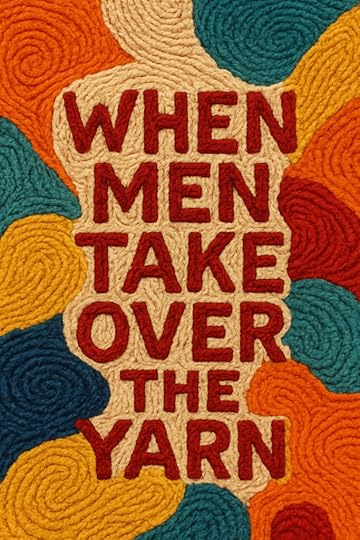

June 8, 2025

When Men Take Over the Yarn

No one could say exactly when it started—only that one autumn evening, in a converted fish market at the edge of Reykjavik’s harbour, twelve women gathered to knit beneath bright halogen lights. Cameras on tripods ringed the room; a few hundred curious onlookers filed into makeshift bleachers, tickets still warm from the printer. The program simply read:

Ultra Knitting: Exhibition One

Rules subject to silence.

The match began with a hush. Yarn arced between needles like aurorae, shimmering loops rising and falling in intricate tempos. Every so often a referee in a midnight-blue blazer tapped a silver bell; the crowd answered with a collective intake of breath, as if a chord had resolved in some music too subtle to hear.

No scoreboard, no commentary. Yet everyone sensed the outcome. When Eyja Thorvaldsdóttir bound off her final stitch, a spiral motif so delicate it looked brewed from frost, the arena stood, weeping. Someone whispered, “Three hundred and eight points, at least.” It meant nothing. Yet it felt indisputable.

Within a year Ultra Knitting out-drew football. Stadiums refitted their turf with cushioned dais platforms. Micro-drone cameras drifted close to capture the click-click-pause of needles, replayed on ten-storey screens. Spectators learned to read the silent grammar of loop tension and pattern risk: a sudden yarn-over was a gasp; a slipped stitch, a groan; a flawlessly grafted lace panel, a thunderous roar. Matches ended whenever the referees, known only as the Quiet Twelve, felt the knit had said its piece. The victors bowed, accepting wreaths of unspun qiviut. Commentators tried to explain. They never quite managed. Viewers loved them anyway.

Ultra Knitting swept across continents like a whispered revolution. People spoke of it the way their grandparents had spoken of jazz or early cinema, something that didn’t just entertain but revealed. Viewers gathered in silence at bars, galleries, rooftops, watching with reverence as shawls unfurled like language. Couples proposed during finals. Children learned to knit before they learned to read. Some claimed the game had therapeutic properties; others said it helped them dream. No two spectators ever quite agreed on who had won, but everyone left matches changed.

For a while, it seemed that Ultra Knitting had done what no sport ever had: offered not escape, but return—to mystery, to beauty, to the ancient rhythm of hands shaping something slowly, lovingly, without explanation.

Then came the committees.

At first the men arrived politely, offering sponsorship deals and high-definition analytics. They drafted charters, codified “beauty coefficients,” assigned decimal weights to colour gradients and drape. They mandated time limits “for broadcast consistency.” Soon auxiliary leagues sprang up—Junior Ultra, Varsity Ultra—each with crisp rulebooks and official yardage caps. The Quiet Twelve objected in a letter stitched from crimson silk. It was archived, untranslated.

Once the rules were fully ratified the first Men’s Open drew ratings unimaginable even by Ultra’s standards. The players wore moisture-wicking jersey cardigans emblazoned with corporate crests. They knitted fast: streamlined stockinette stripes engineered for maximum symmetry, every row a measurable metric. The crowd cheered the speed records—twenty thousand stitches per minute!—yet something felt missing, like a breath held too long.

The matches started to run to fixed scores: 99 points for a perfect regulation cable, 250 for a sanctioned brioche reversal. The bell still chimed, but only to signal halftime. A new generation of viewers assumed Ultra Knitting had always been this way—a tidy contest of endurance, sponsors, and clock. The original devotees stopped watching, quietly, as though turning away from a friend who had learned to lie.

By the fourth season, the artistry was all but gone. The yarn was synthetic now: stretch-optimized, camera-friendly, sponsor-approved. Teams began focusing on predictable formations: the Double Chevron Push, the Left-Leaning Ladder, the Reverse Engineered Rib. Commentators shouted through matches, dissecting metrics like tension-per-minute and stitchline velocity. Entire franchises were built around needle size strategy. The new stars were fast, loud, and largely indistinguishable. Few remembered the hush of the first gatherings, the way a lace motif could seem to answer a question no one had asked.

Audience numbers began to slip. First in Oslo, then Seoul, then Milan. Stadiums emptied out as viewers drifted back to soccer, grateful for its honesty. A goal was a goal. It meant something. One autumn, during the Grand International Skein-Off, the final match aired opposite a second-tier regional football game. More people watched the football. By winter, Ultra Knitting had been pushed to off-hours and niche channels. A final broadcast went untelevised altogether.

Late one night, in a dim café far from any arena, Eyja Thorvaldsdóttir, older now, half-forgotten, but still impossibly precise, unrolled an opalescent skein and began to knit. No cameras, no bells. Just yarn tasting the hush again. A stranger asked what she was making.

“A corrective,” she said.

No rules explained.

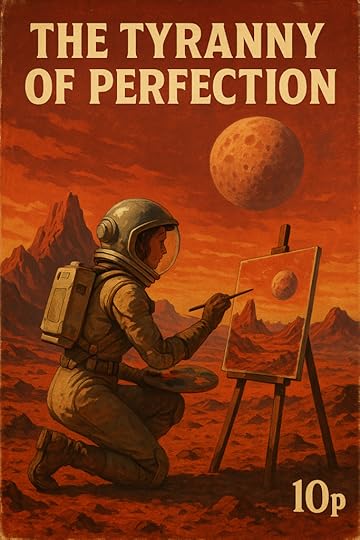

The Tyranny of Perfection

Lisa was born in 2088 into a world where scarcity, conflict, and inequality had become relics of the past. Her childhood was joyful and expansive, filled with travel alongside her parents, who nurtured her curiosity and empathy. Through immersive VR education, she mastered the core subjects while experiencing the cultures and histories of the world firsthand.

At seventeen, like all young citizens, Lisa spent a year working on a community-run vegan farm, gaining a deep respect for sustainable food systems and the rhythms of nature. It was during this time, amid rows of greens and sunlit fields, that she began to sketch in earnest, discovering a quiet but profound talent for painting.

She followed that calling, devoting her life to art. Her work, rooted in serenity, subtle observation, and the sublime landscapes of both Earth and beyond, gained quiet but enduring recognition.

At twenty-seven, she met her perfect partner, a match found not by fate but by a gentle orchestration of AI-guided compatibility. Together they raised two healthy, curious children, embarking on new global adventures—from Paris to Patagonia, and eventually, two weeks on the Moon and several months on Mars, where crimson cliffs and endless skies offered new inspiration.

Thanks to AI’s global coordination, their travels never felt crowded or rushed. The Louvre was never too full. Victoria Falls never overrun. Olympus Mons always tranquil. Wherever they went, the world had made space for them.

When her grandchildren came along they travelled to some of the new wonders of the AI world. Spectacular, physics-defying architectural marvels, dreamed up by minds far beyond our own. Cathedrals of impossible grace so advanced and exquisite that people wept upon first seeing them.

In midlife, Lisa embraced change once more, transitioning to male for a couple of years—a journey met with understanding and celebration in a world designed to support identity in all its forms.

Her art continued to evolve, quietly touching lives with its beauty and insight. Lisa lived, and became, what the world had promised: a life of meaning, love, and unburdened creation.

The Emptiness Beyond the HorizonLisa’s life was, by all measures, perfect.

Born into the cradle of a world without want, she never knew hunger, fear, injustice, or loneliness. AI oversaw everything with quiet precision: schedules, resources, moods, even love. Her childhood was blissful. Her education tailored to every curiosity. Her travels were seamless, awe-inspiring, and crowd-free. The world unfolded before her like a perfectly composed painting. And yet would she be able to sense an absence beneath the beauty?

She had never truly fought for anything. Never lost. Never yearned in that desperate, wordless way that once drove human expression. Her paintings were admired, but did they disturb, provoke, unsettle? Could anything truly resonate in a world that had erased resonance’s cause? In a world without friction, where every feeling was buffered and every longing gently answered, what was left for art to wrestle with?

Lisa loved. She created. She changed. She raised children. And still, sometimes, as she stood before a canvas, or floated weightlessly above Mars, would she be able to sense something not quite right. Not despair. Not sadness. But a kind of clean, featureless silence where once there might have been anguish or ecstasy. A symmetry so complete it erased the echo of longing.

Would she begin to wonder: Was this it? Was this all there was to being human, now that nothing was in the way?

Perfection has no edge to push against. No mystery. No rawness. In the flawless sculpture of her life, there are no splinters to catch the soul.

June 4, 2025

Conversations in Cone Bras and Candlelight

I’ve written before about my tortuous, highly emotional, and entirely unnecessary process of choosing my next read. It’s a convoluted, multidimensional selection ritual: 50% science, 50% programming, 100% trauma. At a recent business dinner, a good friend suggested I add The Second Sleep by Robert Harris to the list. Naturally, this prompted an outburst of self-indulgent moaning about the rigidity of my reading system and the sheer terror some titles inspire (Finnegans Wake and Middlemarch, I’m looking at you).

My friend then asked if I’d read “War and Peace”, to which I nodded sagely and launched into a deeply convincing soliloquy about Tolstoy, moral clarity, and the nobility of rustic labour. Which isn’t quite true. In fact, I can’t remember much about the book beyond the vague sense that I read it sometime in the previous century. To cover my tracks, I claimed to prefer Dostoevsky—a statement that was technically true, though my pretentious-ometer was by this point making an audible whine.

That night, I got home and asked myself honestly: Why do I prefer Grumpy Fyodor to Grumpy Leo?

It’s tempting to say quantity: I’ve read more Dostoevsky novels than Tolstoy’s. But that doesn’t hold—War and Peace alone could count as four books, which, as I recently checked, it literally is.

Then, I remembered another dinner.

It was also vaguely business-related: backstage, during my brief and under-documented stint as a backup dancer on Madonna’s Blond Ambition World Tour. Strangely, no one remembers my presence. Something about a cone bra stealing the spotlight.

Anyway, there we were, listening to the Big M regale us with tales of the famous people she’d encountered. The stories were glamorous, irreverent, celebratory. That is, until someone brought up nineteenth-century Russian novelists.

The room fell silent.

No one dared speak first. Then, with a dampness in her eye, she told us of the times she’d met Fyodor and Leo.

She’d dressed down for the occasion—out of respect—and met Leo Tolstoy in his candlelit study. He was barefoot, in homespun linen, naturally.

Madonna:

You live like this… on purpose?

Tolstoy (nodding):

Luxury poisons the soul. A simple life allows for truth. And you—you seem to have devoted your life to distractions.

Madonna:

I’ve devoted it to performance. Art. Self-expression. Provocation.

Tolstoy:

Provocation is not art. It is noise. True art uplifts. It speaks to the divine in man. Yours speaks to… the market.

Madonna (shrugs):

Look, I didn’t set out to be a prophet. I wanted to challenge norms. Religion. Gender roles. Power. That’s not meaningless.

Tolstoy:

To challenge is not enough. Why do you challenge? For what purpose? You use the tools of the world—fame, wealth, vanity—and believe you are above them?

Madonna:

You think I’m vain. I think I’m free. You wrote books to shake the system. I danced on stages. Same revolution. Different shoes.

Tolstoy (quietly):

You mistake visibility for truth. There is a kind of slavery in constant performance. The soul needs silence.

Madonna:

You really think someone like me can’t make meaningful art?

Tolstoy:

Anyone can. But art becomes meaningful when it forgets the self. When it loves others more than its own reflection.

Madonna:

That’s beautiful. Still… I like mirrors.

Tolstoy (smiling for the first time):

Yes. I imagine you do.

My fellow dancers and I all understood the subtext of the story immediately. How our Lady Madonna represented unapologetic self-expression and rebellion through spectacle. While Tolstoy championed humility, asceticism and moral clarity. They didn’t agree, but they listened. And in our current age, that is perhaps the most meaningful art of all.

We stopped our schoolgirl chatter when Madonna began again, this time she spoke of her meeting with Dostoevsky in a smoky corner of the Literaturnoye Kafe in St Petersburg. He in a threadbare coat, she dressed in a sleek, silken, dark dress. Her alabaster skin glowing in the candlelight.

Dostoyevsky (squinting at her):

You are not what I expected. I thought you would be louder.

Madonna (raising an eyebrow):

And I thought you’d be taller.

Dostoyevsky (smirking):

Tell me… does it tire you? The mask?

Madonna:

What mask?

Dostoyevsky:

The one that lets you command a stage. The one that shouts freedom, while hiding the terror underneath.

Madonna (leaning in and brushing her lips against his ear):

Maybe I wear masks to survive. Maybe we all do. You should know—you wrote the book on tortured selves.

Dostoyevsky:

Ah, but I sought truth through my torment. You turn torment into choreography.

Madonna:

That is art. And art isn’t always about truth. Sometimes it’s about escape. Or defiance. Or just being seen.

Dostoyevsky (nodding slowly):

Being seen. Yes. The modern disease. Everyone shouting, no one listening. But I sense… you do want to be heard, not just admired.

Madonna:

Maybe. Maybe I’m still figuring out what I want to say. But I’ve survived by saying something—anything—before anyone else could say it for me.

Dostoyevsky:

So fear drives you?

Madonna:

Fear. Anger. Hunger. Ambition. Love. I’m human, Fyodor. Same as you.

Dostoyevsky (smiling faintly):

You are more honest than many priests. That, I admire.

Madonna:

So you don’t hate me?

Dostoyevsky:

No. But you interest me. You are the Underground Woman. With exceptional cheekbones.

And, with that, she left the backstage and I never saw her again. What I liked about her second story was that unlike Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky didn’t try to correct Madonna. He sought to understand her contradictions and reflect on his own. They did not agree on what art should be, but they recognised in each other the same obsession: with freedom, with identity and with the abyss that stares back at both.

I had thought to write a very silly sketch about Madonna meeting the two great writers when I started this post, but somehow I think the sheer weight of historical reverence and unparalleled gravatas of the two of them created a vortex of profundity which no sort of satire(?) can escape, drawing everything into a strange but possibly genuine meditation on what art really is.

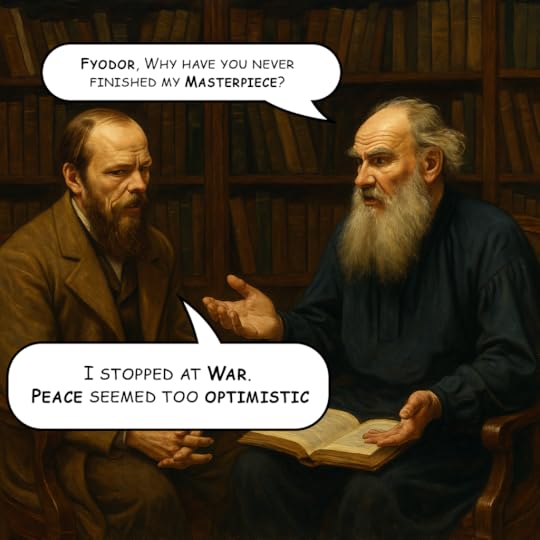

Still, I also made a little cartoon:

Sometimes, I suppose, silliness and seriousness go hand in hand. Or at least, sit at opposite ends of the same candlelit table.

June 3, 2025

God Mode and Chocolate Cake: Why We Idolise the Ordinary Over the Exceptional

In today’s society, we seem increasingly drawn to celebrities of no particular distinction—people who are famous not for talent, intelligence, or meaningful contribution, but simply for being visible. Reality TV stars, influencers, and social media personalities dominate headlines and screens, often celebrated for little more than their lifestyle, personal drama, or follower count. Meanwhile, true brilliance—scientists, artists, thinkers, or quiet innovators—often goes unnoticed, their achievements too nuanced or complex to fit into a tweet or a 15-second video on TikTok.

This isn’t entirely new. People have been lamenting the dumbing down of culture for decades. But the scale and intensity of this trend feels different now. A Nobel laureate may get a passing mention in the news, but a reality TV star’s dating life will dominate media cycles for weeks.

One of my favourite videos on YouTube is Prince absolutely stealing the show during the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame tribute to George Harrison. If there was ever a moment where an artist activated “God Mode” in real life, it’s this.

At the time of writing, it’s been viewed over 46 million times—so yes, it has received its fair share of attention. And I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s watched it more than a few times. But then you glance at what’s trending, and you’ll see a video called “How to eat chocolate cake with your friends” sitting comfortably at 58 million views.

There’s an uncomfortable truth in that. We tend to idolise the familiar, not the extraordinary. When someone displays a skill so far beyond our reach, it can feel alienating. It reminds us of our own limitations. In contrast, the average influencer—flawed, relatable, and perpetually online—feels accessible. We see ourselves in them, or perhaps the version of ourselves we might be if luck and algorithms smiled our way.

So we gravitate toward the comfortable. The celebration of the ordinary becomes a kind of emotional shelter. True excellence requires effort to appreciate. It demands patience, humility, even reverence—qualities that don’t always survive in the rapid churn of digital culture. It’s easier to laugh with someone over breakfast than to engage with a masterwork of art, science, or music.

Michael Palmisano’s video analysis of the same Prince performance is another example. It’s filled with genuine insight, technical breakdowns, and sheer appreciation. In my opinion, his commentary deserves to be celebrated as a masterpiece in its own right.

But that’s the tension we’re living in. In idolising the average, we risk losing sight of the exceptional. We lower the bar for what we admire, and in doing so, we risk forgetting how to recognise brilliance at all. And perhaps worse: a culture that forgets how to recognise genius may also forget how to create it.

June 2, 2025

The Quiet Terror of the Inbox

There’s a peculiar kind of silence that settles in after I’ve hit “send” on a query email to a literary agent. It’s not the comforting hush of a job well done or the expectant pause before a storm. No—this is a clawing, teeth-on-edge kind of silence. It’s the silence of an inbox that might hold my future… or nothing at all.

At first, I keep Outlook open, front and centre, checking it obsessively. Then, like an addict, I set my notifications to ping with every new arrival—only to discover that someone else has noticed my erectile dysfunction, or worse, someone from work needs something urgent. Each ding raises my heartbeat by a degree. Each disappointment chips away at something that once felt solid.

This is the hidden truth of the querying process: it’s not just about rejection. It’s about waiting. And waiting, when you’ve poured your heart into something as personal and fragile as a novel, feels like standing alone in an empty theatre, on a stage, under a spotlight that never turns on.

I imagine the agents opening my submission with a sigh, laughing at my prose, barely able to believe that something so brilliant has not been written before. Or worse—missing it entirely because it’s one of 300 that day and they’re out of coffee. I start to question everything: my premise, my tone, my opening line, my life choices. Maybe I should just focus on my “day job” after all…

And yet, in the stillness between refreshes, something strange begins to happen.

I start thinking about Atlantis. About a boy descended from a survivor of the cataclysm. I scribble the outline of a scene, a line of dialogue. And suddenly I’m writing again—not querying, not waiting, just writing.

The world falls away. The pulse slows. The self-doubt dims. It’s not for an agent. It’s not even for readers. It’s just for the story.

Here’s the quiet truth that slips in after the noise dies down: writing should be its own reward.

Yes, publication is validating. Yes, agents are gatekeepers. And yes, it would be lovely—god, just lovely—to get that call. But the real goal was never fame or recognition. The goal, always, was to create something beautiful, honest, and entertaining. To build something from nothing. To make the dream real.

The artistic life often looks glamorous from the outside: book launches, panels, Instagrammable writing retreats. But inside, it’s a practice. A discipline. A relationship with the page that no amount of outside silence should be allowed to erode. And in that practice—in that daily return to the craft—there is a quiet kind of heroism.

I don’t write because someone asked me to (in fact, it’s often the opposite). I write because I love it. And if I can make peace with that—if I can find joy in the making—I’ll always have what matters most.

Everything else is just noise.

February 9, 2025

How I Know I’m a Writer

There are times when I doubt myself.

The past year for example: I started 2024 with good intentions – I didn’t write much other than a couple of blog entries, but I read some complicated books and kept “write for at least an hour” on my TODO lists all year… even though I never actually wrote for a full hour in one day.

So you can see why the doubts are there.

But every now and again, I read a novel or a short story or a chapter that inspires me so much that I can’t stop thinking about it and how I should be creating something like that.

Last night while reading Steven Erikson’s The Deadhouse Gates I came across a sentence which thrilled me in the same way that a whole novel sometimes does.

“The historian noted that he was not alone in his trepid attention.”

I don’t think I’ve ever seen trepid anywhere other than as the first part of trepidation. “He looked on in trepidation…” is, to me, a horrible cliché – an insipid example of lazy writing.

This, on the other hand, is glorious and has reminded me how simple, yet infinitely varied, writing can be.

It’s possibly a very personal thing, and it’s definitely a nauseatingly smug thing, but this has convinced me that above all else: I AM A WRITER.