What’s the opposite of a placebo?

Last week I posted about the mock-Latin origins of gazebo and, tangentially, about Jane Austen and ha-has.

My point about gazebo is that it imitates Latin, specifically, the second conjugation first-person future indicative. Two other words with the same grammar immediately come to mind: placebo and nocebo. One is familiar in its modern psychological sense but goes back to mediaeval Latin; the other is a relatively modern invention, far less often used than its positive twin.

You’ll probably have come across placebo in one of its two modern meanings; a) ‘a medicine or procedure prescribed for the psychological benefit to the patient rather than for any physiological effect’; or b) ‘a substance that has no therapeutic effect, used as a control in testing new drugs’ (definitions taken from the Online Oxford Dictionary).

The first meaning goes back to 1770 and is defined with admirable and elegant concision in this 1811 quotation from a medical dictionary:

Placebo,… an epithet given to any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient.

R. Hooper, Quincy’s Lexicon-medicum (new edition)

A 1938 quotation, from a journal of the American College of Physicians, sceptically and wittily explodes much of the history of medicine:

The second sort of placebo, the type which the doctor fancies to be an effective medicament but which later investigation proves to have been all along inert, is the banner under which a large part of the past history of medicine may be enrolled.

Annals of Internal Medicine vol. 11 1417

The earliest OED citation for the second meaning, i.e. as a control, is from 1950, but I’ve no idea if that is truly the earliest evidence for that use (trigger warning for those who prefer data as an uncount noun):

It is… customary to control drug experiments on various clinical syndromes with placebos especially when the data to be evaluated are chiefly subjective.

Journal of Clinical Investigation vol. 29 108/2

The scientific literature is full of examples of experiments where people have derived real physiological benefits from medicines or drugs which in principle exerted no actual effect on their bodies. In other words, any benefit may originally have been ‘all in the mind’, but it translated to the body.

If a placebo is a medicine given to a patient for its beneficial psychological effect, what, then, is a nocebo, literally ‘I shall harm’?

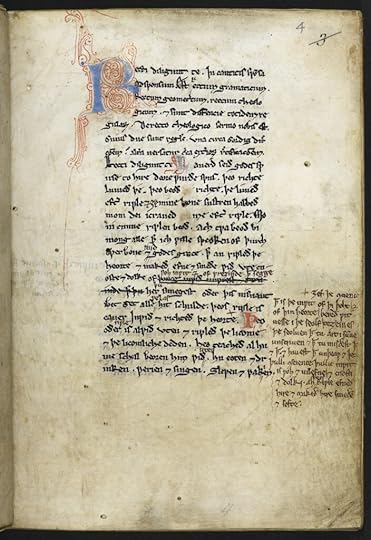

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r.

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r. Again, according to Oxford, it’s ‘a detrimental effect on health produced by psychological or psychosomatic factors such as negative expectations of treatment or prognosis.’

It’s first recorded from 1961.

That’s a harder idea to get your head around. A couple of the OED examples seem helpful. The OED also points out that it’s mainly used in the phrases nocebo effect and nocebo response and that it often applies to negative effects experienced after the administration of a placebo.

Attempts to define the secondary effects of placebos, i.e., the nocebo effect.

Encephale vol. 58 486 1969

Patients experiencing the nocebo effect… presume the worst, health-wise, and that’s just what they get.

Washington Post 30 April (Home edition) f1/2 2002.

I’ve looked for examples, and AI was helpful. For instance, patients might experience nausea or drowsiness when taking medication if they’ve been told they will, even if what they’re taking has no physiological effect because it’s a placebo. In other words, placebos and nocebos both illustrate how our expectations and beliefs can affect our experience in direct ways.

(Note, incidentally, the plurals in –os rather than –oes.)

Such thoughts were far from the mind of the person who first recorded placebo back in the early thirteenth century, in the Ancrene Riwle, the rules governing the life of anchorite nuns.

Like lavabo, discussed in last week’s post, the word’s origins are religious. It repeats the first word of the first antiphon of the Vespers for the Dead ‘Placebo Domino in regione vivorum’ (Psalm 114, Vulgate), ‘I will please the Lord in the land of the living.’

The other second conjugation verb in English we probably all know is habeas corpus. But that’s for another time.