Across The River and Into The Trees, Ernest Hemingway (1950)

The Colonel is talking to his driver, Jackson:

“That’s Torcello directly opposite us,” the Colonel pointed. “That’s where the people lived that were driven off the mainland by the Visigoths. They built that church you see there with the square tower. There were thirty thousand people lived there once and they built that church to honor their Lord and to worship him. Then, after they built it, the mouth of the Sile River silted up or a big flood changed it, and all that land we came through just now got flooded and started to breed mosquitoes and malaria hit them. They all started to die, so the elders got together and decided they should pull out to a healthy place that would be defensible with boats, and where the Visigoths and the Lombards and the other bandits couldn’t get at them, because these bandits had no sea-power. The Torcello boys were all great boatmen.

So they took the stones of all their houses in barges, like that one we just saw, and they built Venice.” He stopped. “Am I boring you, Jackson?”

“No, sir. I had no idea who pioneered Venice.”

“It was the boys from Torcello. They were very tough and they had very good taste in building. They came from a little place up the coast called Caorle. But they drew on all the people from the towns and the farms behind when the Visigoths over-ran them. It was a Torcello boy who was running arms into Alexandria, who located the body of St.

Mark and smuggled it out under a load of fresh pork so the infidel customs guards wouldn’t check him. This boy brought the remains of St. Mark to Venice, and he’s their patron saint and they have a cathedral there to him. But by that time, they were trading so far to the east that the architecture is pretty Byzantine for my taste. They never built any better than at the start there in Torcello. That’s Torcello there.”

…

That’s my town. There’s plenty more I could show you, but I think we probably ought to roll now. But take one good look at it. This is where you can see how it all happened.

But nobody ever looks at it from here.”

“It’s a beautiful view. Thank you, sir.”

“O.K.,” the Colonel said. “Let’s roll,”

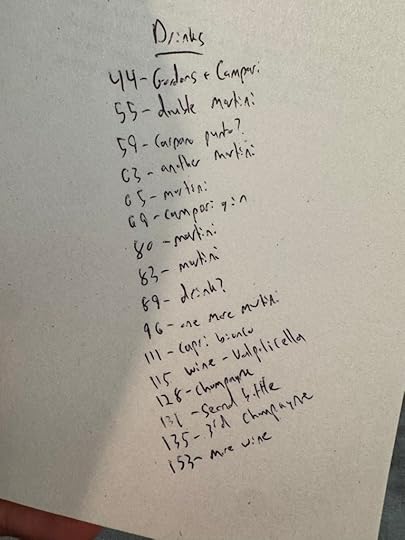

This book takes place over three days. On day one, this is what the Colonel drinks (with page numbers):

This is not one of Hemingway’s more popular books. In Farewell To Arms, Sun Also Rises, and For Whom The Bell Tolls, the main character is young, cool, brave, competent, about as awesome a guy as you can think up. The Colonel, when we meet him, is calling his boatman a jerk. And he’s old (50) and busted up. He used to be a general but lost that rank. His mind is on pain, the past.

The Austrian attacks were ill-coordinated, but they were constant and exasperated and you first had the heavy bombardment which was supposed to put you out of business, and then, when it lifted, you checked your positions and counted the people. But you had no time to care for wounded, since you knew that the attack was coming immediately, and then you killed the men who came wading across the marshes, holding their rifles above the water and coming as slow as men wade, waist deep.

If they did not lift the shelling when it started, the Colonel, then a lieutenant, often thought, I do not know what we would be able to do. But they always lifted it and moved it back ahead of the attack. They went by the book.

If we had lost the old Piave and were on the Sile they would move it back to the second and third lines; although such lines were quite untenable, and they should have brought all their guns up very close and whammed it in all the time they attacked and until they breached us. But thank God, some high fool always controls it, the Colonel thought, and they did it piecemeal.

All that winter, with a bad sore throat, he had killed men who came, wearing the stick bombs hooked up on a harness under their shoulders with the heavy, calf hide packs and the bucket helmets. They were the enemy.

But he never hated them; nor could have any feeling about them. He commanded with an old sock around his throat, which had been dipped in turpentine, and they broke down the attacks with rifle fire and with the machine guns which still existed, or were usable, after the bombardment. He taught his people to shoot, really, which is a rare ability in continental troops, and to be able to look at the enemy when they came, and, because there was always a dead moment when the shooting was free, they became very good at it.

But you always had to count and count fast after the bombardment to know how many shooters you would have. He was hit three times that winter, but they were all gift wounds; small wounds in the flesh of the body without breaking bone, and he had become quite confident of his personal immortality since he knew he should have been killed in the heavy artillery bombardment that always preceded the attacks. Finally he did get hit properly and for good. No one of his other wounds had ever done to him what the first big one did. I suppose it is just the loss of the immortality, he thought. Well, in a way, that is quite a lot to lose.

The Colonel visits a place where he wounded fighting with the Italian army in the first World War – Fossalta. It’s the same place Hemingway himself was wounded while serving as a Red Cross volunteer. You could read The Colonel as being how Frederick Henry from Farewell to Arms turned out. This is almost a sequel.

The Colonel has a nineteen year old countess who loves him, but it’s accepted they can have no future together. This book is gloomy. We’re in a postwar Italy with bomb craters and ex-Fascists. In Hemingway’s other books lots of people die, but they weren’t Americans. The romance and European sexiness of Hemingway’s early books is gone. The Colonel recounts military ugliness, death, ordering men to die on orders:

The first day there, we lost the three battalion commanders.

One killed in the first twenty minutes and the other two hit later. This is only a statistic to a journalist. But good battalion commanders have never yet grown on trees; not even Christmas trees which was the basic tree of that woods. I do not know how many times we lost company commanders how many times over. But I could look it up.

They aren’t made, nor grown, as fast as a crop of potatoes is either. We got a certain amount of replacements but I can remember thinking that it would be simpler, and more effective, to shoot them in the area where they detrucked, than to have to try to bring them back from where they would be killed and bury them. It takes men to bring them back, and gasoline, and men to bury them. These men might just as well be fighting and get killed too.

Does it seem plausible that a beautiful nineteen year old Venetian countess would want to spend her time prodding a 51 year old US Army Colonel to tell her war stories? Bear in mind he’s an alcoholic grouch. It COULD be that’s more of a middle-aged guy’s fantasy? The countess doesn’t seem like a fully realized character to me. But so what? We’re still dealing with one of the best to ever do it here, there are amazing scenes and passages and moments that come to life.

Hemingway spoke about this book, as yet unpublished, in The New Yorker profile by Lillian Ross from 1950. That profile, you’ll recall, opens with Ross meeting Hemingway at Idlewild airport after a flight from Havana. When she arrives he’s got a fellow passenger in a headlock:

[Hemingway] crooked the arm around the briefcase into a tight hug and said that it contained the unfinished manuscript of his new book, “Across the River and into the Trees.” He crooked the arm around the wiry little man into a tight hug and said he had been his seat companion on the flight. The man’s name, as I got it in a mumbled introduction, was Myers, and he was returning from a business trip to Cuba. Myers made a slight attempt to dislodge himself from the embrace, but Hemingway held on to him affectionately.

“He read book all way up on plane,” Hemingway said. He spoke with a perceptible Midwestern accent, despite the Indian talk. “He like book, I think,” he added, giving Myers a little shake and beaming down at him.

“Whew!” said Myers.

“Book too much for him,” Hemingway said. “Book start slow, then increase in pace till it becomes impossible to stand. I bring emotion up to where you can’t stand it, then we level off, so we won’t have to provide oxygen tents for the readers. Book is like engine. We have to slack her off gradually.”

“Whew!” said Myers.

Hemingway released him. “Not trying for no-hit game in book,” he said. “Going to win maybe twelve to nothing or maybe twelve to eleven.”

Myers looked puzzled.

“She’s better book than ‘Farewell,’ ” Hemingway said. “I think this is best one, but you are always prejudiced, I guess. Especially if you want to be champion.” He shook Myers’ hand. “Much thanks for reading book,” he said.

Ross asks him his own opinion on the book:

“What do you think?” he said after a moment. “You don’t expect me to write ‘The Farewell to Arms Boys in Addis Ababa,’ do you? Or ‘The Farewell to Arms Boys Take a Gunboat’?” The book is about the command level in the Second World War. “I am not interested in the G.I. who wasn’t one,” he said, suddenly angry again. “Or the injustices done to me, with a capital ‘M.’ I am interested in the goddam sad science of war.” The new novel has a good deal of profanity in it. “That’s because in war they talk profane, although I always try to talk gently,” he said, sounding like a man who is trying to believe what he is saying. “I think I’ve got ‘Farewell’ beat in this one,” he went on. He touched his briefcase. “It hasn’t got the youth and the ignorance.” Then he asked wearily, “How do you like it now, gentlemen?”

The parts about the command level in the Second World War are most interesting. Here’s a small section:

“Tell me about when you were a General.”

“Oh, that,” he said and motioned to the Gran Maestro to bring champagne. It was Roederer Brut ’42 and he loved it.

“When you are a general you live in a trailer and your Chief of Staff lives in a trailer, and you have bourbon whisky when other people do not have it. Your G’s live in the C.P. I’d tell you what G’s are, but it would bore you. I’d tell you about GI, G2, G3, G4, Gs and on the other side there is always Kraut-6. But it would bore you. On the other hand, you have a map covered with plastic material, and on this you have three regiments composed of three battalions each. It is all marked in colored pencil.

“You have boundary lines so that when the battalions cross their boundaries they will not then fight each other.

Each battalion is composed of five companies. All should be good, but some are good, and some are not so good.

Also you have divisional artillery and a battalion of tanks and many spare parts. You live by co-ordinates.”

He paused while the Gran Maestro poured the Roederer Brut ’42.

“From Corps,” he translated, unlovingly, cuerpo d’Ar-mata, “they tell you what you must do, and then you decide how to do it. You dictate the orders or, most often, you give them by telephone. You ream out people you respect, to make them do what you know is fairly impossi-ble, but is ordered. Also, you have to think hard, stay awake late and get up early.”

“And you won’t write about this? Not even to please me?”

[The Colonel, once a general, goes on at some length about why he couldn’t possibly write any of this down.]

I can’t say the book is about the command level of WW2. The book is about Venice, being wounded, hurt, pain, wine, hotels, memory, impending death, regret, doomed love, being fifty-one. The Colonel keeps telling himself not to be morbid.

How Hemingway wrote it, from the Ross profile:

Hemingway poured himself another glass of champagne. He always wrote in longhand, he said, but he recently bought a tape recorder and was trying to get up the courage to use it. “I’d like to learn talk machine,” he said. “You just tell talk machine anything you want and get secretary to type it out.” He writes without facility, except for dialogue. “When the people are talking, I can hardly write it fast enough or keep up with it, but with an almost unbearable high manifold pleasure.

In his New York Times review of Across The River and Into the Trees, John O’Hara scolded The New Yorker for the profile’s emphasis on Hemingway’s drinking. O’Hara’s review boils down to “this may not be his best but it’s Hemingway.” I agree!

The title of the book comes from the dying words of Stonewall Jackson, recounted in the book. Here is the version reported by Stonewall Jackson’s medical officer, Hunter McGuire:

A few moments before he died he cried out in his delirium, “Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action ! Pass the infantry to the front rapidly! Tell Major Hawks ,” then stopped, leaving the sentence unfinished. Presently a smile of ineffable sweetness spread itself over his pale face, and he cried quietly and with an expression as if of relief, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees “; and then, without pain or the least struggle, his spirit passed from earth to the God who gave it.

The best parts of ATRAITT were a tribute to Venice:

I ought to live here. On retirement pay I could make it all right. No Gritti Palace. A room in a house like that and the tides and the boats going by. I could read in the mornings and walk around town before lunch and go every day to see the Tintorettos at the Accademia and to the Scuola San Rocco and eat in good cheap joints behind the market, on, maybe, the woman that ran the house would cook in the evenings.

I think it would be better to have lunch out and get some exercise walking. It’s a good town to walk in. I guess the best, probably. I never walked in it that it wasn’t fun. I could learn it really well, he thought, and then I’d have that.

It’s a strange, tricky town and to walk from any part to any other given part of it is better than working cross-word puzzles. It’s one of the few things to our credit that we never smacked it, and to their credit that they respected it.

I liked too the part where they eat a lobster:

Just then the lobster was served.

It was tender, with the peculiar slippery grace of that kicking muscle which is the tail, and the claws were excel-lent; neither too thin, nor too fat.

“A lobster fills with the moon,” the Colonel told the girl.

“When the moon is dark he is not worth eating.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“I think it may be because, with the full moon, he feeds all night. Or maybe it is that the full moon brings him feed.”

“They come from the Dalmatian coast do they not?”

“Yes,” the Colonel said. “That’s your rich coast in fish.”

Another good part is when the Colonel eats a thin slice of sausage and then some clams at the market.

They made this book into a film in 2022. It seems challenging to me, most of the story takes place in the Colonel’s head, not much happens, except some conversations, and like we said, gloomy. There are two duck hunts, a car ride, a long dinner, and a wandering in Venice, but that’s about it for action in the present time. Still, from the trailer it looks like Lieb Schreiber found something in the role:

Some sources on the last words of Stonewall Jackson:

DEATH OF STONEWALL JACKSON – by Dr. Hunter McGuire

Stonewall Jackson’s Last Words

Did Stonewall Jackson “cross” or “pass” over the river?

Valipolcella/Valipolcello comes up a lot, wine, from this region:

Photo credit to NuKeglus on Wikipedia.