Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare: Rebound to Michelin Glory

I had dinner at Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare this week and enjoyed it thoroughly. Some consider it New York’s longest running soap opera of fine dining, and indeed its history is dramatic.

Moe Issa, born and raised in Brooklyn, began his career as a Pepsi truck driver in the 1980’s and 90’s. During those years, he dreamed of opening a high-quality neighborhood grocery store like some he admired in Manhattan. He opened Brooklyn Fare at the corner of Schermerhorn and Hoyt in downtown Brooklyn. The community welcomed it for its carefully chosen produce and sophisticated grocery items.

Not content to be only a grocer, Moe recruited César Ramirez, formerly chef de cuisine at Bouley, to open a restaurant in the back of the store. It thrived beyond what anyone could have expected in this modest setting, becoming the first Brooklyn restaurant to earn three Michelin stars. The NY Times described Issa as “Medici to Ramirez’s Donatello.”

In 2016 he opened a branch of Brooklyn Fare in Manhattan’s Hells Kitchen neighborhood, and Ramirez moved the restaurant, once again to a room in the back of the grocery store. It became one of the city’s most lauded fine-dining establishments.

Their partnership came crashing down in 2023 when Issa fired Ramirez, prompting lawsuits in which each accused the other of defamation and embezzlement. The ensuing publicity led to Michelin’s revoking all three of its stars and the closure of the restaurant.

Undeterred, Issa reopened later that year, with Max Natmessnig and Marco Prins as co-executive chefs. Both chefs were alumni of the restaurant, having worked under Ramirez in its early Brooklyn days. Natmessnig, an Austrian native, brought experience from Michelin-starred kitchens like Alois in Munich and Steirereck in Vienna, while Prins, from the Netherlands, had worked at Oud Sluis and Ukiyo in New York.

Michelin re-awarded two stars. Based on my experience there this week, I suspect the third star will be forthcoming soon. If it is not, it could only be because of lingering feelings from the bitter dispute and not from any shortcomings of the current menu.

You enter through the ordinary-looking small grocery store. “Where is the restaurant?” I had to ask. “Down that aisle, in the back,” the clerk told me.

Once through those unpromising doors, you’re in a different world. The highly polished wooden chef’s table, from which the place takes its name, wraps around a world-class kitchen in which toqued chefs perform a graceful ballet amid gleaming copper cookware.

There is no printed menu. In the morning of the day of our reservation, the maître d’ called to ask about our dietary preferences. I told him my brother didn’t want to eat any red meat. “Not a problem,” he said. “There are just two courses containing meat, and we can substitute seafood preparations for him. How about you? Would you like the same?” “No,” I said. “The meat will be fine for me.”

Then later in the day, he called back to ask how my brother felt about squab. I said squab would be fine. “Thanks, we’re deciding between squab and duck for that dish,” he said.

Sure enough, there were two dishes containing meat, and they prepared and served excellent alternatives to my brother without making any fuss about it. Such attention to detail is rare and much appreciated.

The meal began with bluefin tuna tartare from Japan with pickled grilled corn and Idaho potato taco. Piquant flowers and leaves and a hint of wasabi at the bottom gave layers of unexpected flavors. With it, the sommelier poured glasses of Krug Grande Couvée 171eme and advised that it was to go with this and the two other amuse bouches to come.

Next was a grilled California spring pea nori tartelette with Hudson valley foie gras. The peas were exceptional, barely grilled, tender moist and flavorful. The foie gras provided a nice textural counterpoint.

The final amuse bouche was a celery root tart with Japanese A5 wagyu tartare, gribiche flavors and dried jiidori eggyolk. For my brother, they replaced the wagyu with yellowfin tuna. He said it was excellent. I’m not ordinarily a fan of raw beef, but the wagyu was unctuous and the subtle caper flavor of the gribiche and the slight crunch of the dried yolk topping made the dish outstanding. The flavor and texture of the tart itself made it more than a mere container for its contents.

For the next two courses, our sommelier poured what she called the only Japanese sake she knew that had a French name, Kuheiji Eau du Désir. She said it especially appealed to both chefs who love to combine French and Japanese esthetics. She described it as oleaginous, and it indeed had a uniquely creamy mouth-feel. I could have happily drunk nothing but this with the rest of the meal.

The next dish was a standout. Nestled in a cedar box of cracked ice were a pacific northwest Center Bay oyster with agua chile vinaigrette, jalapeno foam and guacjillo oil, and a hot smoked Pemaquid mussel with a vadouvan lemon vinaigrette and codium seaweed.

I think that adding sauces to excellent oysters usually amounts to gilding the lily, but here the three different chiles of the vinaigrette, the foam and the oil were a three-note chord that underscored the perfection of the oyster. The mussel would have been fine on its own, but the sauce and seaweed brought a layered complexity that raised it to a much higher level of interest.

Next came an uni preparation the chef described as urchin panna cotta, with shellfish jelly, Japanese geoduck, Alaskan king crab, Portuguese carabinieros, shiso, grapefruit and Hokkaido sea urchin.

The uni itself was perhaps the star of the show, but the members of its supporting cast were no less remarkable. The urchin was about as good as that delicious roe ever gets, but the red carabinieros prawn was equally excellent. The urchin panna cotta, almost hidden beneath all this shellfish deliciousness, was a lovely accompaniment.

The next wine was described as an acquired taste. If so, I acquired it immediately. Anapea Village’s Kvareli ‘Sandro’ Amber Dry Wine is a distinctive Georgian wine crafted from the indigenous Kisi grape. The winemaking process involves fermenting the grapes on their skins in traditional qvevri—large clay vessels buried underground. The result is orange hued, bone dry, and reminiscent of dried apricots.

It was chosen to accompany just one dish, warm gently smoked Maine brook trout, with a grilled leek/trout bone vinaigrette, horseradish and trout roe. The trout was so tender it was easily cuttable with the spoon that also scooped up the roe. Their pop in the mouth was a pleasant counterpoint to the soft and smoky trout.

For the next two dishes, the sommelier poured a 2021 Wechsler Morstein Riesling GG, dry, highly concentrated, floral with a long intense finish.

The dishes this lovely Riesling accompanied were both finished on the restaurant’s binchotan grill. Binchotan is a Japanese oak charcoal, esteemed for its ability to maintain smokeless high heat for many hours. The placement of the grill high above the embers lets the grill chef delicately control the cooking.

I think scallop with caviar is always a winning combination, and CTBF’s version was especially pleasing with a vin jaune sauce, fig leaf oil and a generous helping of Kaluga Queen caviar.

Abalone from Ezo Japan, braised and then lacquered over the grill, was served over koshihikari rice, morels and white grilled French asparagus with a seaweed and grilled lettuce sauce. The abalone was nicely tender and smoky. The asparagus was remarkably soft and flavorful. Altogether an excellent dish.

The dishes were so uniformly excellent that it’s hard to pick a favorite, but the next was clearly a candidate: grilled Norway langoustine, nam prick chili paste, a sauce made from the heads of the langoustine with saté flavors, mango purple curry chutney and a pandan foam. The langoustine itself was superb, on par with L’Ambroisie’s, by which this curry-sauced version may well have been inspired.

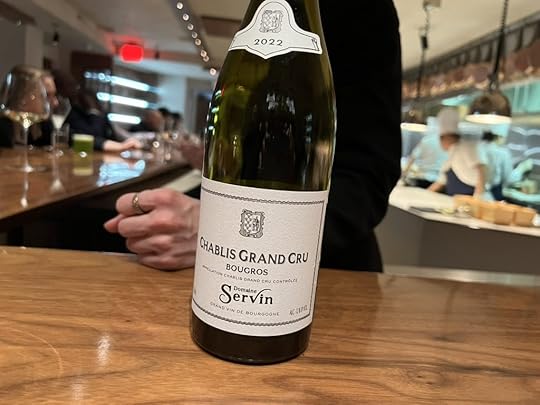

To accompany the langoustine, the sommelier poured a 2022 Chablis from Domaine Servin, Bougros Grand Cru.

The next dish was something of a mixed blessing: wild caught Holland turbot with a szegediner goulash sauce, sauerkraut caraway foam and grilled wagyu beef tongue. The turbot itself was excellent, cut from a big 18-pound fish, gently and perfectly grilled. The smokey goulash sauce was a creative and pleasant accompaniment, and the foam was sublime. I take issue with the wagyu tongue. I didn’t get why it was paired with the fish and didn’t think it added anything to it, nor did it, in my view, go with the sauce and the foam, both of which went brilliantly with the fish. I would have much preferred to just have more of the delicious turbot.

The next dish more than made up for this. A dry aged Hudson valley duck, binchotan grilled, with a French duck press blood-fortified sauce. and Szechuan pepper foam, foie gras terrine, verjus pickled grapes, grilled savoy cabbage and black Périgord truffle. Perhaps there could have been more truffle, as what there was was hard to notice among the rich and diverse flavors of the rest of the dish. But aside from that nit-picking, each component was distinctively excellent and each gave a separate discernable pleasure.

The duck dish was accompanied by a 2022 Clos de la Chapelle “En Carelle” Volnay, perhaps the best wine of the evening, delicate with a long subtle finish.

As a sort of epilog to the story told by the complex duck dish, the chef gave us a little cup of consommé made out of the grilled duck bones infused with matsutake mushroom and pine needle oil. Its depth of flavor made it a fine closing statement.

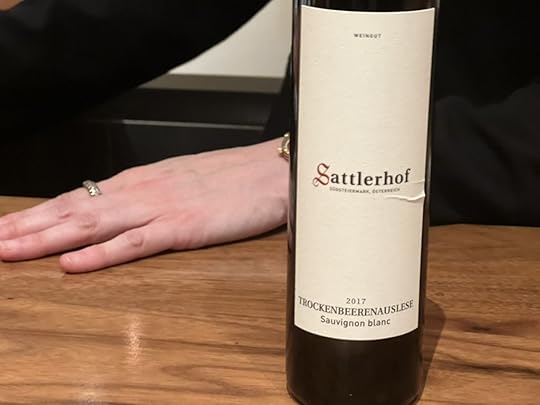

To go with the desserts, we were served a Sattlerhof Trockenbeerenauslese, Styria 2017. There is no such thing as a bad or even mediocre trockenbeerenauslese. This was a fine example of the species. To make it, individual grapes are picked that exhibit just the right amount of botrytis-induced concentration of sugars. The resulting wine combines sweetness, structure and complex aromas. It’s the pinnacle of the old German system of wine classification.

The first desert was a pickled rhubarb rice pudding with strawberry sake granita and a pear hibiscus sorbet.

The second dessert was a laminated Japanese fujisan brioche lacquered with Japanese 30 year old whiskey and coconut ice cream.

More than merely tasty sweets, each of the desserts was a precisely executed combination of ingredients whose distinctive flavors came together to tell the story of the chefs’ desire to display the harmony of Japanese and French esthetics and techniques.

The mignardise consisted of:

white chocolate mocha opera cakesmores tartelette with espresso ganache, apricot jam and vanilla guimauve (the French precursor to marshmallows)yuzu raspberry pate de fruit

While maintaining the quality of the previous incarnation of CTBF, chefs Max and Marco told me that they want each bite to tell a story of their own life’s journeys. I think they succeeded admirably.

In Vedat’s review of CTBF in the Ramirez era, he compared it very favorably to other more widely knownplaces that were often named as NYC’s best. I believe that comparison is still valid. If anyone knows of a New York restaurant that provides more pleasure than the current version of CTBF, I’d love to know what it is. I doubt that there are any.

Vedat Milor's Blog

- Vedat Milor's profile

- 23 followers