Vedat Milor's Blog

September 23, 2025

Amador: Austria’s First Three-Star Michelin Restaurant

Am I ungrateful, I wonder, to write anything but an unqualified rave review of Juan Amador’s Vienna restaurant? It was, after all, the first restaurant in all of Austria to receive three Michelin stars, and it held them alone for over a decade until Steirereck came along.

Michelin stars are indispensable to the financial success of a high-quality restaurant, so it is understandable that a savvy chef must try to create what the Michelin reviewers want to see. Social media too plays a role in the viability of top restaurants, so it is likewise understandable that chefs aiming to draw in affluent and discerning diners must pay attention to what works there.

Both of these things are, sadly for me, at odds with what makes a restaurant enjoyable. The thing I value most is simple: the food has to be delicious. Instagram cannot depict how the food tastes. It can only show what it looks like. Michelin seems to value the cleverness of a chef in crafting unique and original compositions of ingredients more than it cares about how pleasurable it is to eat the food.

Juan Amador is a chef of the highest level of skill and creativity. You can almost hear how the gears turn in his mind when you are presented with one of his dishes. They are clever. Original. Ingenious. So much so that how they taste seems to come second in importance. It’s not that they aren’t enjoyable. Most of them certainly are. But I am left with the impression that he is hoping diners will say, “Oh, that’s so clever,” rather than, “That was delicious.”

Amador sits in a brick lined former wine cellar that was originally a part of Vienna’s underground water infrastructure.

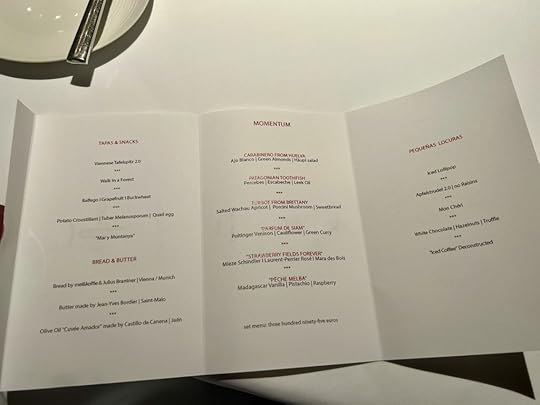

The sole dinner option is the tasting menu. Here it is:

The first snacks are good examples of what I mean by prioritizing cleverness over taste.

The Viennese Tafelspitz 2.0 is meant to convey the essence of that dish in two mouthfuls. The spoon, shown for scale, is miniature, maybe a centimeter across. The soup is a very reduced beef broth over one star-shaped wafer each of carrot and potato. The roule is filled with beef tartare and topped with horseradish. Is the dish perfectly crafted? Yes. Is it better in any way than tafelspitz? Not really.

The next bite is called Walk in a Forest. I’ve had similarly titled dishes elsewhere, for example at Manresa, that were enjoyable compositions of vegetables, each carefully selected for excellence, individually prepared and combined into a composition in which each bite gave a distinct pleasure. This was nothing of that sort. The whole thing is one small mouthful, apparently sculpted with tweezers and a magnifying glass: an impressive miniature, but not especially enjoyable to eat.

I could go on in a similar vein about the rest of the snacks, but in fairness to chef Amador, each was masterfully prepared. Here are pictures of each:

Mar y muntanya

Mar y muntanya Potato crustillant, tuber melanosporum, quail egg

Potato crustillant, tuber melanosporum, quail egg

As an add-on, I ordered this composition, highly recommended by the server: oysters, caviar, beurre blanc ice cream, almond milk foam, tamarind oil. Each component was perfect. The idea of making ice cream out of beurre blanc is original, but did I enjoy it more than I would have a mouthful of excellent vanilla ice cream? Not really.

The bread and butter were delicious and, frankly a relief from the preciousness of the starters. The olive oil is a special cuvee made exclusively for Amador, and truly outstanding. The spread is made from buffalo milk with lovage oil. It was excellent.

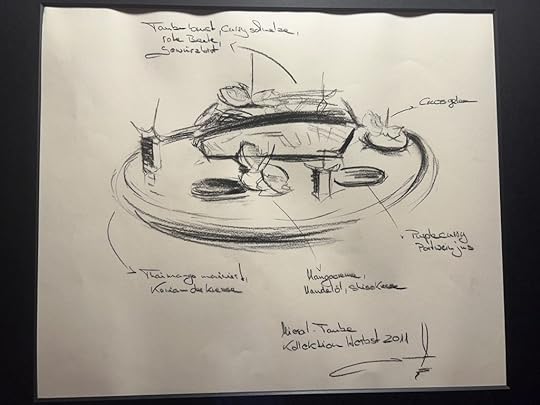

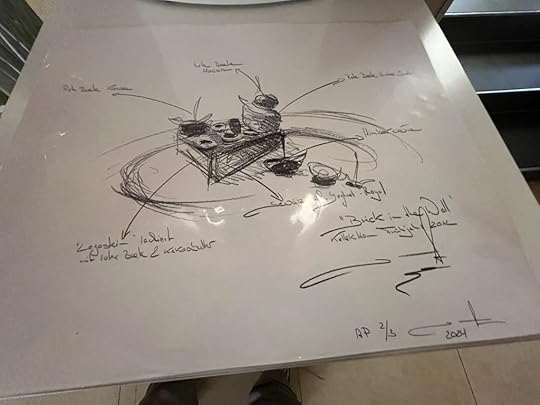

Was I unfair in my criticism of the first dishes? Each showed the highest levels of craftmanship and creativity. But thinking it over, I stand by what I said. The chef prioritizes cleverness over pleasure. This was foreshadowed by the architectural style sketches of some dishes that are displayed in the entrance way. Here are a couple of them:

A server noticed me looking at them and came over to discuss them. “Yes,” he said proudly, “Chef has a clever and original concept for each dish he creates.”

Moving onto the main dishes, presented in a sequence Amador calls Momentum, I will try to be more balanced in my critiques.

The carabineiro with ajo blanco (a cold Andalusian soup that predates gazpacho) was an unqualified success. The prawn was an outstanding example of its species—exquisitely fresh and flavorful and cooked the exact right amount. The soup and the slight crunch of the green almonds complimented it nicely.

The Patagonian toothfish was flaky and sublimely tender, and the “escabeche,” really just a single ingredient (perhaps a slice of summer squash) stand-in for that complex preparation, the leek oil and the hazelnut foam underscored the fish beautifully. The percebes, however, did not do justice to how delicious those barnacles can be. In an attempt to pare them down to a simple bite, the flavor and texture that makes them so sought-after were mostly lost. Again, the tendency to favor cleverness over taste showed itself.

The turbot from Brittany, salted Wachau apricot, porcini and sweetbread was excellent. The sauce, which was a surprising Jerusalem artichoke foam, provided a subtle nuttiness that unified the perfection of each of the ingredients. I found no fault with this delicious dish.

Parfum de Siam was an excellent venison dish, so titled for the green Thai curry flavored sauce. The cauliflower foam, puree and wafer were masterful. Altogether a great composition.

The first dessert, Strawberry Fields Forever, is described as containing two varieties of strawberry, Mieze Schindler and Mara des Bois. Both are famed as exceptionally flavorful and delicate. I would guess the former were used in the rosé champagne ice while the latter were served whole.

The second dessert, pêche melba, was a deconstructed version of Escoffier’s classic. It was certainly enjoyable, but I didn’t think it improved upon the original.

We were now more than four hours into this odyssey and I was happy to see that the mignardises, which Amador calls pequenas loquras, arrived all together rather than one after another. They were tasty and, though I hesitate to reuse the word, clever.

My experience at Amador left me mildly exasperated and craving the excellence of simplicity. Is there any place these days that provides that? Happily, our journey took us next to two places that did: Taubenkobel in the tiny Styrian village of Schützen am Gebirge, and Steirereck am Pogusch, the country outpost of the owners of Steirereck am Stadtpark, which I previously described as a strong candidate for the best restaurant in Austria. My meal at Amador, Austria’s only other Michelin three star, made me feel more certain that Steirereck deserves that title. I will review Taubenkobel and Pogusch soon.

September 10, 2025

Steirereck: Vienna’s Three-Star Culinary Revelation

Austria is not generally known for culinary innovation. Its best-loved dishes are judged not for creativity, but for perfect adherence to traditional standards. Tafelspitz—boiled beef and root vegetables—and wienerschnitzel have not varied in a very long time. In the whole country there was just one Michelin three starred restaurant until this year when Steirereck was awarded its own. We had lunch there and found it to be miraculously original in Austria’s tradition-bound gastronomic landscape.

Steirereck means the Styrian corner. Styria, the region known as Austria’s green heart, is the home of many of the country’s iconic and ancient traditional dishes. The restaurant began over fifty years ago as a small local place owned by the Reitbauer family. Nothing about its origins, and certainly not its name, led anyone to envision the temple of originality it would become.

In the late 1990’s the family’s son Hans Reitbauer Jr joined the company with ambitions to transform Steirereck entirely. His efforts were met with skepticism and a fair amount of hostility from the public, fearing the loss of a well-liked homey traditional place. But with the backing of his family, he and his wife Birgit persevered and created something truly special.

The architectural marvel they built to house their vision alerts visitors that they’re about to enter something refined and entirely modern. Visually, it is a shocking surprise among the classical monuments of imperial Vienna.

Floor to ceiling mirrored glass panels bring the lovely green Stadtpark right into the interior. The design breaks up the space into a number of nooks that give diners the feeling of being in small intimate rooms.

Styria is Austria’s principal wine region and the sommelier was impressively knowlegable of the best Austrian wines, of course in addition to those of the rest of Europe as well. He brought us glasses of a Thomas Schwarz bubbly to begin the meal.

Before the amuse bouches, a gentleman whose sole job seemed to be bread sommelier wheeled the bread cart to our table. Did he visit each of Vienna’s best bakeries that morning and select their best? I suspect so. The cart held an astonishing variety of excellent breads.

A succession of amuse bouches foreshadowed the philosophy of the meal to come: complexity and originality not for their own sake, but to give pleasure. Many of the components came from Steirereck’s own farm at Pogusch and a rooftop herb garden.

We chose the seven-course tasting menu. Each course had two dishes to choose from. We usually each picked a different one.

The two first courses were:

Tomato Diversity with Citrus, Lavendar and ChamomileEach little grilled tomato was prepared separately and then combined into a lovely composition. Some were marinated with citrus, bergamot and lemon balm, others pickled with lavender, verjus and lemon verbena, and others marinated in mushroom tea. A couple pieces of confit kohlrabi and some red onion pickled in chamomile blossom fond completed the composition. It sat in a soup of jellied tomato water and chamomile blossom oil. Each tomato vied for the title of best tomato I’ve ever tasted.

Young Carrots with Enoki, Apricot and Marigold

Young Carrots with Enoki, Apricot and Marigold

The carrots were glazed with cardamom butter, accompanied by steamed enoki mushrooms braised in carrot mushroom jus. The apricots were preserved in spiced verjus. Yarrow, amaranth and anise hyssop were marinated in ginger and lemongrass. Orange marigold oil brought the vegetable mixture together.

These first courses raised a question. Was it really worthwhile to combine so many ingredients? I’m not entirely sure, but each bite hit with an initial pleasure and then asked us to decipher its component flavors, an enjoyable exercise.

To accompany the first course dishes, we were brought a Nikolaihof Riesling and a Krutzler Gemischter Satz from Austria’s Südburgenland. Rather than blending wines from different vinyards, the gemischter satz approach grows several varieties in a single small plot, harvests and vinifies the grapes together.

Second courses were also entirely plant-based:

Sunflower with Chanterelles, Tomato and Field Cucumber

The grilled and glazed heart of a sunflower sat atop roasted chanterelles with preserved sunflower stems, dried field cucumber and tomato, in a pool of roasted sunflower and pumpkin seed sauce spiced with coriander, lime and perilla oil, an extract of the seeds of the shiso plant.

Young Artichokes with Melon Cucumber, Groundcherries and Poppy.

A young artichoke was split lengthwise, one half braised with madeira and thistle oil, the other steamed and glazed with poppy miso. Grilled and marinated melon cucumber and groundcherry slices sat on top of sauteed baby spinach, young coconut, and dried groundcherry, all in a pool of artichoke braising jus, coconut water, lime and poppy seed oil.

The chef makes so much use of groundcherries—they must be in season—that I thought I ought to mention what they are. They’re the fruit of the physalis plant. They grow encased in a paper-like skin and have a pleasantly tart flavor. They’re also known as cape gooseberries or Chinese lanterns.

With the second courses we were served a French Anjou Noir from Domaine Belargus, and a Polz sauvignon blanc from South Styria.

Next came two fish dishes:

Catfish with String Beans, Plum and Lemon Savory

Crisp grilled catfish and steamed yellow string beans, topped with a scoop of greengage plum jam studded with lemon savory leaves from the Steirereck garden all sat in a foamed string bean butter sauce.

Eel with pointed cabbage, spruce tips and pepperoncini

Flamed Bodensee eel, glazed with groundcherry and spruce tips sat next to braised and roasted pointed cabbage (spitzkohl) with little radishes in pickled cabbage butter sauce with pepperoncini and smoked eel oil.

The fourth course, which we both chose, was Kid Goat Ribs with Pointed Pepper, Elderberries and Grapefruit. It was accompanied by a Envínate Migan Tinto from the Canary Islands, vibrant, fruity and minerally.

Charcoal grilled kid goat ribs were deboned and glazed with elderberries. They sat on top of a delightful salad of sugar snaps, watermelon, grapefruit, shiso and lemon verbena in a pointed pepper watermelon sauce with lemon verbena oil.

Next came a dish I hesitated to try: Fawn with Summer Squash and Lemon Balm. Did I want to eat Bambi? Well, we think nothing of eating young lambs, I reasoned. The fawn was exceptionally tender and flavorful.

Along with it we were served Pranzegg from Italy’s Bolzano Valley basin, made from old vines of indigenous varieties and biodynamically grown.

The meat was roasted and glazed with red currant, fennel and Szechuan pepper, accompanied by lemon balm marinated spinach and summer squash with preserved salted lemon, sauced with an exquisite fawn velouté.

It was time for the cheese course, and one cart wasn’t sufficient to hold them all. The cheese sommelier brought two carts with a wonderful variety of soft, hard, strong, mild and blue cheeses. We took his recommendations for the best local cheeses. Each was perfectly ripe and excellent.

To go with the cheese, our principal server offered some bread varieties we had thus far neglected to try.

The desserts were in all respects up to the quality of the meal.

Bitterorange of Schönbrunn Palace with Buttermilk, Comb Honey and Bee Polen.

A granita of a variety of bitterorange once favored by the emperor was topped with honey and pollen from Steirereck’s hives and a delightful bitterorange cream.

Our server brought the honeycombs in a specially designed cart that hummed with the recorded sound of the bees. The sound effect was so convincing that I wondered if they were going to fly out into the room.

Viennese Mangomelon with Fennel Pollen, Passionfruit and Rice.

Mangomelon is a cucurbit that produces orange colored mango-flavored fruit. They were candied, dried, and made into an ice cream.

Mirabelle Plums with Coconut, Fig Leaf and Groundcherries.

Mirabelle Plums with Coconut, Fig Leaf and Groundcherries.

A caramelized puff pastry shell held marinated Mirabelle plums, coconut, pecan praline, groundcherries, rummed raisins and roasted coconut ice cream in a whisky Mirabelle sauce with fig leaf oil.

With the desserts, we were served a 2019 Stadlman Auslese, and Nolandes Gut Warth Honigwein, essentially a mead.

The mignardise were each created in honor of specific pieces by Strauss, whose two hundredth birthday is now being celebrated.

Would we care for some herbal tea to go with the petits fours? Our server brought a cart of growing herbs and snipped some to make a concoction for us.

Not one but two other carts, wheeled in by their expert, brought a great variety of after dinner drinks, one cart full of local schnapps and the other of imported ones.

Espresso came accompanied by a couple of delicate little treats.

Steirereck is in my opinion one of the best restaurants in the world and a strong candidate for the best in Austria. If you visit Vienna, it would be a mistake to miss it.

April 26, 2025

Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare: Rebound to Michelin Glory

I had dinner at Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare this week and enjoyed it thoroughly. Some consider it New York’s longest running soap opera of fine dining, and indeed its history is dramatic.

Moe Issa, born and raised in Brooklyn, began his career as a Pepsi truck driver in the 1980’s and 90’s. During those years, he dreamed of opening a high-quality neighborhood grocery store like some he admired in Manhattan. He opened Brooklyn Fare at the corner of Schermerhorn and Hoyt in downtown Brooklyn. The community welcomed it for its carefully chosen produce and sophisticated grocery items.

Not content to be only a grocer, Moe recruited César Ramirez, formerly chef de cuisine at Bouley, to open a restaurant in the back of the store. It thrived beyond what anyone could have expected in this modest setting, becoming the first Brooklyn restaurant to earn three Michelin stars. The NY Times described Issa as “Medici to Ramirez’s Donatello.”

In 2016 he opened a branch of Brooklyn Fare in Manhattan’s Hells Kitchen neighborhood, and Ramirez moved the restaurant, once again to a room in the back of the grocery store. It became one of the city’s most lauded fine-dining establishments.

Their partnership came crashing down in 2023 when Issa fired Ramirez, prompting lawsuits in which each accused the other of defamation and embezzlement. The ensuing publicity led to Michelin’s revoking all three of its stars and the closure of the restaurant.

Undeterred, Issa reopened later that year, with Max Natmessnig and Marco Prins as co-executive chefs. Both chefs were alumni of the restaurant, having worked under Ramirez in its early Brooklyn days. Natmessnig, an Austrian native, brought experience from Michelin-starred kitchens like Alois in Munich and Steirereck in Vienna, while Prins, from the Netherlands, had worked at Oud Sluis and Ukiyo in New York.

Michelin re-awarded two stars. Based on my experience there this week, I suspect the third star will be forthcoming soon. If it is not, it could only be because of lingering feelings from the bitter dispute and not from any shortcomings of the current menu.

You enter through the ordinary-looking small grocery store. “Where is the restaurant?” I had to ask. “Down that aisle, in the back,” the clerk told me.

Once through those unpromising doors, you’re in a different world. The highly polished wooden chef’s table, from which the place takes its name, wraps around a world-class kitchen in which toqued chefs perform a graceful ballet amid gleaming copper cookware.

There is no printed menu. In the morning of the day of our reservation, the maître d’ called to ask about our dietary preferences. I told him my brother didn’t want to eat any red meat. “Not a problem,” he said. “There are just two courses containing meat, and we can substitute seafood preparations for him. How about you? Would you like the same?” “No,” I said. “The meat will be fine for me.”

Then later in the day, he called back to ask how my brother felt about squab. I said squab would be fine. “Thanks, we’re deciding between squab and duck for that dish,” he said.

Sure enough, there were two dishes containing meat, and they prepared and served excellent alternatives to my brother without making any fuss about it. Such attention to detail is rare and much appreciated.

The meal began with bluefin tuna tartare from Japan with pickled grilled corn and Idaho potato taco. Piquant flowers and leaves and a hint of wasabi at the bottom gave layers of unexpected flavors. With it, the sommelier poured glasses of Krug Grande Couvée 171eme and advised that it was to go with this and the two other amuse bouches to come.

Next was a grilled California spring pea nori tartelette with Hudson valley foie gras. The peas were exceptional, barely grilled, tender moist and flavorful. The foie gras provided a nice textural counterpoint.

The final amuse bouche was a celery root tart with Japanese A5 wagyu tartare, gribiche flavors and dried jiidori eggyolk. For my brother, they replaced the wagyu with yellowfin tuna. He said it was excellent. I’m not ordinarily a fan of raw beef, but the wagyu was unctuous and the subtle caper flavor of the gribiche and the slight crunch of the dried yolk topping made the dish outstanding. The flavor and texture of the tart itself made it more than a mere container for its contents.

For the next two courses, our sommelier poured what she called the only Japanese sake she knew that had a French name, Kuheiji Eau du Désir. She said it especially appealed to both chefs who love to combine French and Japanese esthetics. She described it as oleaginous, and it indeed had a uniquely creamy mouth-feel. I could have happily drunk nothing but this with the rest of the meal.

The next dish was a standout. Nestled in a cedar box of cracked ice were a pacific northwest Center Bay oyster with agua chile vinaigrette, jalapeno foam and guacjillo oil, and a hot smoked Pemaquid mussel with a vadouvan lemon vinaigrette and codium seaweed.

I think that adding sauces to excellent oysters usually amounts to gilding the lily, but here the three different chiles of the vinaigrette, the foam and the oil were a three-note chord that underscored the perfection of the oyster. The mussel would have been fine on its own, but the sauce and seaweed brought a layered complexity that raised it to a much higher level of interest.

Next came an uni preparation the chef described as urchin panna cotta, with shellfish jelly, Japanese geoduck, Alaskan king crab, Portuguese carabinieros, shiso, grapefruit and Hokkaido sea urchin.

The uni itself was perhaps the star of the show, but the members of its supporting cast were no less remarkable. The urchin was about as good as that delicious roe ever gets, but the red carabinieros prawn was equally excellent. The urchin panna cotta, almost hidden beneath all this shellfish deliciousness, was a lovely accompaniment.

The next wine was described as an acquired taste. If so, I acquired it immediately. Anapea Village’s Kvareli ‘Sandro’ Amber Dry Wine is a distinctive Georgian wine crafted from the indigenous Kisi grape. The winemaking process involves fermenting the grapes on their skins in traditional qvevri—large clay vessels buried underground. The result is orange hued, bone dry, and reminiscent of dried apricots.

It was chosen to accompany just one dish, warm gently smoked Maine brook trout, with a grilled leek/trout bone vinaigrette, horseradish and trout roe. The trout was so tender it was easily cuttable with the spoon that also scooped up the roe. Their pop in the mouth was a pleasant counterpoint to the soft and smoky trout.

For the next two dishes, the sommelier poured a 2021 Wechsler Morstein Riesling GG, dry, highly concentrated, floral with a long intense finish.

The dishes this lovely Riesling accompanied were both finished on the restaurant’s binchotan grill. Binchotan is a Japanese oak charcoal, esteemed for its ability to maintain smokeless high heat for many hours. The placement of the grill high above the embers lets the grill chef delicately control the cooking.

I think scallop with caviar is always a winning combination, and CTBF’s version was especially pleasing with a vin jaune sauce, fig leaf oil and a generous helping of Kaluga Queen caviar.

Abalone from Ezo Japan, braised and then lacquered over the grill, was served over koshihikari rice, morels and white grilled French asparagus with a seaweed and grilled lettuce sauce. The abalone was nicely tender and smoky. The asparagus was remarkably soft and flavorful. Altogether an excellent dish.

The dishes were so uniformly excellent that it’s hard to pick a favorite, but the next was clearly a candidate: grilled Norway langoustine, nam prick chili paste, a sauce made from the heads of the langoustine with saté flavors, mango purple curry chutney and a pandan foam. The langoustine itself was superb, on par with L’Ambroisie’s, by which this curry-sauced version may well have been inspired.

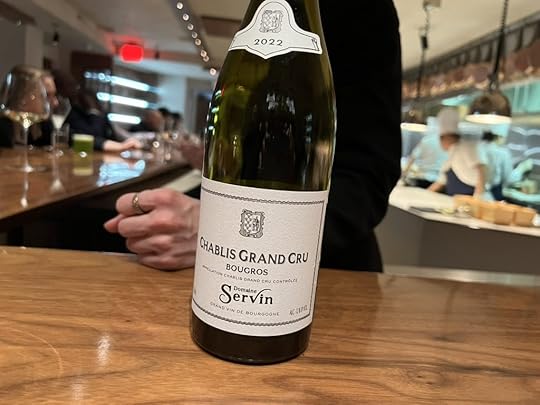

To accompany the langoustine, the sommelier poured a 2022 Chablis from Domaine Servin, Bougros Grand Cru.

The next dish was something of a mixed blessing: wild caught Holland turbot with a szegediner goulash sauce, sauerkraut caraway foam and grilled wagyu beef tongue. The turbot itself was excellent, cut from a big 18-pound fish, gently and perfectly grilled. The smokey goulash sauce was a creative and pleasant accompaniment, and the foam was sublime. I take issue with the wagyu tongue. I didn’t get why it was paired with the fish and didn’t think it added anything to it, nor did it, in my view, go with the sauce and the foam, both of which went brilliantly with the fish. I would have much preferred to just have more of the delicious turbot.

The next dish more than made up for this. A dry aged Hudson valley duck, binchotan grilled, with a French duck press blood-fortified sauce. and Szechuan pepper foam, foie gras terrine, verjus pickled grapes, grilled savoy cabbage and black Périgord truffle. Perhaps there could have been more truffle, as what there was was hard to notice among the rich and diverse flavors of the rest of the dish. But aside from that nit-picking, each component was distinctively excellent and each gave a separate discernable pleasure.

The duck dish was accompanied by a 2022 Clos de la Chapelle “En Carelle” Volnay, perhaps the best wine of the evening, delicate with a long subtle finish.

As a sort of epilog to the story told by the complex duck dish, the chef gave us a little cup of consommé made out of the grilled duck bones infused with matsutake mushroom and pine needle oil. Its depth of flavor made it a fine closing statement.

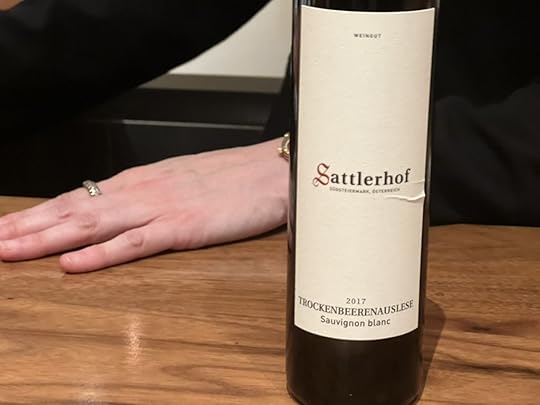

To go with the desserts, we were served a Sattlerhof Trockenbeerenauslese, Styria 2017. There is no such thing as a bad or even mediocre trockenbeerenauslese. This was a fine example of the species. To make it, individual grapes are picked that exhibit just the right amount of botrytis-induced concentration of sugars. The resulting wine combines sweetness, structure and complex aromas. It’s the pinnacle of the old German system of wine classification.

The first desert was a pickled rhubarb rice pudding with strawberry sake granita and a pear hibiscus sorbet.

The second dessert was a laminated Japanese fujisan brioche lacquered with Japanese 30 year old whiskey and coconut ice cream.

More than merely tasty sweets, each of the desserts was a precisely executed combination of ingredients whose distinctive flavors came together to tell the story of the chefs’ desire to display the harmony of Japanese and French esthetics and techniques.

The mignardise consisted of:

white chocolate mocha opera cakesmores tartelette with espresso ganache, apricot jam and vanilla guimauve (the French precursor to marshmallows)yuzu raspberry pate de fruit

While maintaining the quality of the previous incarnation of CTBF, chefs Max and Marco told me that they want each bite to tell a story of their own life’s journeys. I think they succeeded admirably.

In Vedat’s review of CTBF in the Ramirez era, he compared it very favorably to other more widely knownplaces that were often named as NYC’s best. I believe that comparison is still valid. If anyone knows of a New York restaurant that provides more pleasure than the current version of CTBF, I’d love to know what it is. I doubt that there are any.

March 22, 2025

Tacos, Tradition, and the Michelin Money Machine

The only thing that distinguishes El Califa de Leon by sight, is the guy whose sole function is to take the cash. Few taquerias splooge on such a luxury, but El Califa needs an efficient system, given the swarms of Americans whose Iphone cameras clash like sabres in front of the plancha.

Those who follow such things will be aware that this hole-in-the-wall taqueria in Mexico City was awarded a Michelin star last year. It’s not the first taqueria to get a star, there’s one in Copenhagen owned by a Noma alumnus. Though fairly traditional, the Danish taco stand does apply some of that contemporary technical magic that you’d expect from an ex-Noma chef, say, cooking the pork in a plastic bag at 68°C. I prefer that no plastic bags are harmed in the tenderisation of the pork, but I’m old school.

I can tell if I’ll like a restaurant by asking a single question – has it been doing the same thing for ever? It could be a fancy French hotel, flambéing a crepe tableside, or St John serving hard boiled eggs to men in suits, Etxebarri with their Xtuleta, a trattoria of your choice. Because pleasure in eating is not simply the action of prepared food on the taste buds. Every gustatory experience is mediated by assumptions, habits and memories. We know how entwined yumminess and familiarity are – think about your favourite childhood dessert. So an eatery’s adherence to food traditions, for me at least, is an important precondition for pleasure.

The chef at El Califa de Leon, in the relatively humble San Rafael neighbourhood of Mexico City, tells me that they’ve been doing exactly the same thing since it opened almost 70 years ago, right down to the salsa recipe. They make no attempts to refine or modernise, and there’s not a plastic bag in sight.

You choose between four cuts of meat, 3 of which are from a cow that was slaughtered this morning, the other is from a pig, whose time of death is not advertised. The meat, the chef proudly tells me, has never seen the inside of a fridge, not even a glance. He peels back a dishcloth to show me the stacks of slithered muscle. They’ve been speckled with pieces of beef fat, which will render and coat the lean cuts when they hit the plancha. They look good, well dried and the vibrant red of haemoglobin-rich beef.

There are no seats, just a narrow bar with standing room for three slender diners to rest their plastic plates. One guy flips the meat, a woman cranks tortillas out of a pillow of masa, cooking them to order.

We each take a Gaonera and a Costilla, which I pair with a can of Canada Dry. Costilla means rib, but this is a thin slice of the belly muscle. The Gaonera is their signature, it’s beef fillet, a cut you rarely encounter in Mexico because they export their fillets to places where people pay a premium for lean, lower-flavour cuts. Here it works well, the rendered beef fat and deep sear boosting the underpowered muscle.

Left: The Beef Fillet , Right: The Beef Rib

Left: The Beef Fillet , Right: The Beef RibPink meat, cooked to cuisson, is not the national style. Meat is either cooked til it falls apart (eg Carnitas) or it’s nailed by high heat (such as El Pastor), in which the pleasure is closer to that of crispy bacon – lots of maillard reaction, a deep salty flavour and a total rejection of juiciness. It works, it’s just very different to the European style. Here, the tranche of beef fillet, cooked with a pinch of salt and a few drops of lime juice, is slightly pink! Hallelujah.

The tortilla is tender, almost mallowy, radiating the aroma of toasted corn. Both the meat and the tortilla are the best I’ve had in Mexico, but I’m not sure why. Perhaps it is simply that both elements are at their best – the tortilla only cooked thirty seconds ago and pressed 30 seconds before that. With no moisture lost, it steams as much as it toasts on the plancha.

I keep seeing people describe El Califa as ‘elemental’. As if by distilling tacos to their bare essentials, they have captured nature itself. Frustratingly, I find myself agreeing.

The current Mexico City taqueria du jour, Orinoco, is so dominant that a phenomenon known as Orinocificacion is documented on Tiktok. Taquerias all over the city are copying Orinoco’s red and white branding, and their short but toppings-heavy menu. They offer 6 salsas, roasted onions, a free side of crispy smashed potatoes, pineapple slivers and the usual raw onion / cilantro dice. As a sauce-orientated man who wants always for more, Orinoco is liable to give more pleasure than El Califa. El Califa’s great but sometimes I want a whole apothecary of toppings.

In Mexico it’s surprisingly difficult to get good ingredients. Almost half of the fruit and vegetables are imported, mostly from the US, who’s agricultural output is known to be about as bad as it gets. So, I wondered if this distinguished taqueria would be making its masa from ancestral Mexican maize? On asking, I found that no, the chef did not know where the local tortilleria got it, who delivered the dough each morning. He knew little more about the beef, but as the taqueria’s owner also owns a butchers, we imagine they get fairly good stuff. It seems that traceability and sourcing are not imperatives. Leave that for the likes of Maizajo and Paramo, the forgettable upmarket Mexican restaurants, banging on about heritage blue maize varietals.

I wondered, interrogating the chef while the checks backed up – are traceability and animal welfare bourgeois fetishes? Do they really matter? The chef had no truck with the notion that we must love our livestock. For him, good beef was fresh beef that hadn’t touched a fridge. For me, good beef is pasture-raised and has hung around, maturing in a fridge for at least a month. That’s the beauty of eating food from another tradition, you have to accept that the assumptions you bring to food are just that – assumptions or cultural tastes, and not universal truths.

This leads me to my next question. How, then, can a French tyre manufacturer judge the quality of a taqueria?

When appraising a cuisine you know little about, the best questions you can ask are – does this food work? Does it feel right for the place and time? Does is excel at what it intends to do? But your answers to these questions are still mediated by your assumptions. I want to eat cold, light food during the hot summer months, but try telling that to an Achari Murgh vendor in Delhi. You can certainly say ‘this dish pleases me’, but is it a stretch for the Eurocentric bible of food quality to rate taquerias?

It makes sense for Michelin to award Pujol 2 stars, their style of dining (if not the food) is modelled on Western fine-dining principles. But to come to Mexico City and say ‘this is the best taqueria’, is pretty absurd.

For me, Michelin cannot maintain its values whilst being more inclusive. This is the problem of a universal rating system. For a French company to have a monopoly on food quality assessment is just another example of a cultural hegemony, where certain flavours, styles and behaviours are rewarded because they appeal to the old-world gastronome.

Michelin’s taco dictates are, at best, under-informed. And little known is that nations pay Michelin to have their restaurants assessed. Somewhat unfairly, the poorer the nation, the more they pay. CANIRAC, Mexico’s national restaurant association paid a record 10 million dollars for their 16 stars, the most of any country. For comparison California paid $600,000 and won over 100 Michelin stars. In 2017, Thailand paid 4.4 million dollars, while the year before, the much wealthier South Korea paid only 1 million dollars.

As our tastes shift away from white tablecloths and fawning waiters, Michelin’s attempts to stay relevant do seem to be working. The hype surrounding the Mexico guide has, according to several featured restaurant owners, massively increased their custom.

But when I spoke to the owner of three restaurants in the city, which hit the criteria for a Bib Gourmand but didn’t make it into the guide, I heard a different story. He complained that business was worse than ever, before asking with a flourish of his hand, ‘What the hell do they know about tacos?’ The Michelin Guide validates the quality of a cuisine for an international audience, but for those left out, it can feel like a death sentence.

March 16, 2025

March 5, 2025

Vedat Milor's Blog

- Vedat Milor's profile

- 23 followers