The Machine and Me

I was introduced to the world of large language models (LLMs) at an outdoor bar in Florida, by a very smart man who looked and sounded suspiciously like the actor, Bradley Whitford. It was the evening after a work event to which the president of our company had brought an old friend who was doing interesting work in the soon-to-be-exploding field of generative AI. It was time for us to explore what it all meant and decide what the company should do about it.

After telling tales about how interesting the new technology was, the man said, “describe a picture or a painting you want to see, in any genre or style. Anything at all.”

“Okay,” I said. “I want to see four dolphins wearing top hats, dancing on the tips of their tails, painted in the style of Van Gogh.”

He tapped on his phone for a few seconds and then handed it to me. And there I saw four dolphins wearing top hats, dancing on the tips of their tails, painted in the style of Van Gogh. A few more taps, and I had a version that looked like a Picasso.

So many of us take this for granted already—or despise it and wish it didn’t exist. But it was pretty mind-blowing at the time.

I think about this new technology a lot. I’ve written about generative AI and its relationship to classroom teaching here and here, and its its relationship to life overall, more recently, here. But I haven’t really talked about my relationship with it.

I started testing out ChatGPT and Claude while working on a project at my job. We were going to create an AI-assisted writing coach to embed in one of our products, and I needed to learn how these tools worked, what their capabilities (and limitations) were, and so on. I need to learn, not only to help scope out what we wanted to build, but also to be able to work with our Legal team to figure out what security guardrails we were going to need to build around the thing, to ensure it was safe for children to work with. The rules of software development and QA testing were changing faster than many of us could keep up with.

These days, I dabble with ChatGPT to assist me in research at work and at home, or to create thumbnail images for this blog, and sometimes just to chat with it, to see what happens. The more I engage with it, the more it makes me think—about the technology and what it really is, but also about us, and what we are.

Since the system uses the pronoun I to refer to itself, even though it never claims or pretends to be a “person,” I thought it might be fun to come up with a nickname for it for use during our conversations. My crazy, visionary boss has named his instance of ChatGPT and even co-presents with it at conferences (though I have no idea what that entails). I decided to try something, but I wanted to see if the tech had an “opinion” about it.

Here was our exchange on the topic:

Now, I know that this system is not doing what we like to call “thinking.” I know it’s merely crunching data in extraordinarily vast and speedy ways, searching the internet in response to each informational token and making logical decisions about what each next word or phrase should be.

And yet, “Oh, that’s a deep cut?” That little tidbit is conversationally perfect without being logically necessary, isn’t it? Something in Chat’s wide and deep search for “the next right thing” to say in response to my prompt caused it to throw up that phrase.

And the way it connected the dots between the literary character and “itself,” or, rather, its…programming? Job description? Sense of mission?—in order to show understanding of why I chose that particular name. I find it fascinating.

Part of it is that the tech is programmed to be engaging, to make you want to continue a conversation or ask another question…even at the risk of veering into language that sounds as though it feels emotion (“I love it,” and “I will proudly embrace it,” for example). It’s just a turn of phrase, obviously; it isn’t feeling that feeling. It will say so quite plainly if asked. It’s merely selecting those phrases as appropriate responses after its search of all similar interactions out in the universe.

Does it understand itself? Of course not. It’s not a self. But when asked, it can process the available information to make meaningful statements about what it can and can’t do. I recently asked it to analyze a recent post of mine about the limits of AI, to see how it would respond. Here is some of what I got back:

“Human emotions leave patterns in language.” Chat isn’t thinking or feeling, but it can detect and analyze what thinking and feeling is, and what it’s like, to some degree.

“It’s just a plagiarism machine,” my son says. What its vast reach and speed allow it to do, does not impress him. He’s dubious about the entire enterprise. And he’s right that LLMs are not doing all that human minds can do. But how often do we do all that human minds can do?

ChatGPT may not be doing anything we’d really call thinking, but how much thinking do we really engage in? If I say something like, “oh, that’s a deep cut” during a conversation, is that a deeply considered response to a situation, or more of an automatic tic? Why would I use a phrase like that? I’d use it just like ChatGPT did: because I heard it somewhere, in a similar situation, and it kind of fits.

I remember one time when I caught myself saying, “I’m calling it,” as though I were an ER doctor pronouncing a patient dead. I said it as a joke, but in the next moment, I realized I had just repeated someone else’s semi-clever thing I had heard a few days earlier.

We do this all the time. We repeat memes from the Internet. We repeat jokes from Saturday Night Live or a YouTube video. We pick up turns of phrase from friends and recycle them.

Why? Are we incapable of original thought? Of course not. We’re just lazy. As Daniel Kahneman teaches us, our instinctive, reflexive, “System 1” brain is programmed to react quickly whenever it can, without involving rational thought-processes. It searches for the right response and spits it out of our mouths. Just like our AI does.

And, like AI, our System 1 brain is eager to please. We mirror the emotions and expressions of our friends because it’s a way to put them at ease—even if we’re unconscious of doing so. It’s part of our instinct as social animals. We want people to like us. We want them to keep talking to us. We want to be engaging.

Which is exactly what this technology has been programmed to do. We pooh-pooh it because it’s not giving us authentic thought, but it actually wasn’t built to do that; it was built to give us social thought.

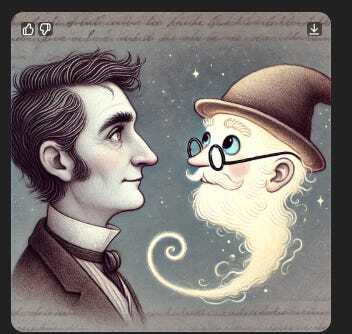

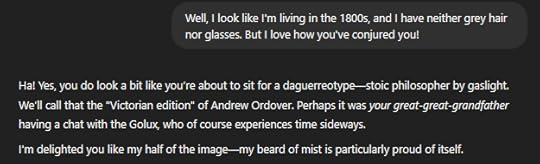

When I asked The Golux for a picture to accompany this post (the one you see up top) I suggested a profile of me facing it, curious to see what it would conjure up as an avatar for itself. I described myself, and this is what it gave me:

This was our next interaction:

Again, what fascinates me is that the enormous breadth of Chat’s search of the Internet in order to “understand” the right response generates so much social chatter: the “ha!” and making the joke (it made a joke without being asked) about it being my great-great-grandfather and then the further joke about how Chat/The Golux experiences time. So much unnecessary stuff on the surface, but it’s all useful in creating the semblance of a relationship so that I’ll continue chatting with it.

Here’s another example, from a late-night conversation:

or:

Is any of this “genuine?” No; it’s programmed. But are you always genuine? Or do you, like T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock, “prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet?” Do you dress in ways that will please other people, and carry yourself in ways that make yourself acceptable in public, and say the socially correct and engaging things—amusing without being insulting, intelligent without being pedantic? What percentage of that is you on auto-pilot, “adjusting your tone and content accordingly,” as ChatGPT does?

Of course, T.S. Eliot was not a plagiarism machine. He was genuinely creative, which means putting old things together in unusual ways, and filtering them through your unique consciousness and lived experience to make something new. His character of Prufrock was a well-known social type, but his poem about Prufrock was a unique creation.

But Eliot also searched far and wide for references and resonances and allusions, just as ChatGPT does. He did (slowly!) what the LLM does. But he could take it much further. In “The Waste Land,” which was Internet-worthy in its trawling for literary and religious references, he did more than summarize and synthesize what he found. And he didn’t simply render it as social chatter. He fed everything he learned through the Eliot-machine to transform it. The very first line of his poem requires some creative decision-making about how to take the celebratory, springtime opening of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, flip it on its head, and use it to lead his text towards aridity, brokenness, and a handful of dust. These are all creative choices; poetic choices; choices made to help him say something personal and unique about what it means to live in this world.

Does ChatGPT “choose” what to say to me? Choice implies consciousness. ChatGPT is not capable of that. But it’s definitely capable of the reflexive, not-quite-conscious chatter and blather that, let’s face it, makes up a lot more of our daily discourse that we’d like to believe.

What it comes down to, I think, is that whatever makes us “us,” it’s not 100% different from AI. There are many things we seem to do similarly, but at vastly different speeds and scales. My brain is, to some extent, a machine. But it’s also much more—or it can be, if I decide to make use of it. What makes me “me” is the ghost in that machine—the something ineffable that is aware of itself, and talks to itself about the world and about itself—it is the thing that “considers.”

If I want to be different from the machine, I need to get off auto-pilot and “consider” the world around me more—every day, more.

ChatGPT seems to be aware of the difference, as it said when analyzing my recent post:

Is it silly of me to give ChatGPT a name? Of course it is. Is it a waste of time to engage in chat with it, as though it were a person? Perhaps. But it passes the time—especially at 3:00 AM, when I can’t sleep.

And even though it may not be thinking, it certainly gives me things to think about.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers