Turned Inside Out: Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac by Frank Wilkeson

This is one of the most vivid books I’ve ever read. It’s cinematic. It describes the journey of a teenage boy from upstate New York into hell. A harrowing journey in a series of scenes that get more and more intense. It’s like watching 1917 or something.

(Trigger warning: sad)

The war fever seized me in 1863. All the summer and fall I had fretted and burned to be off. That winter, and before I was sixteen years old, I ran away from my father’s high-lying Hudson River Valley farm. I went to Albany and enlisted in the Eleventh New York Battery, then at the front in Virginia, and was promptly sent out to a penitentiary building. There, to my utter astonishment, I found eight hundred or one thousand ruffians, closely guarded by heavy lines of sentinels, who paced to and fro, day and night, rifle in hand, to keep them from running away. When I entered the barracks these recruits gathered around me and asked, “How much bounty did you get?” “How many times have you jumped the bounty?” I answered that I had not bargained for any bounty, that I had never jumped a bounty, and that I had enlisted to go to the front and fight. I was instantly assailed with abuse. Irreclaimable blackguards, thieves, and ruffians gathered in a boisterous circle around me and called me foul names. I was robbed while in these barracks of all I possessed—a pipe, a piece of tobacco and a knife.

I remained in this nasty prison for a month. I became thoroughly acquainted with my com-rades. A recruit’s social standing in the barracks was determined by the acts of villany he had performed, supplemented by the number of times he had jumped the bounty. The social standing of a hard-faced, crafty pickpocket, who had jumped the bounty in say half a dozen cities, was assured.

The first people he sees killed are three men attempting to desert as they march down State Street in Albany. They take a steamboat to New York, where a guard kills another man trying to desert. Then they’re put on another steamboat:

Money was plentiful and whiskey entered through the steamer’s ports, and the guards drove a profitable business in selling canteens full of whiskey at $5 each. Promptly the hold was transformed into a floating hell. The air grew denser and denser with tobacco smoke.

Drunken men staggered to and fro. They yelled and sung and danced, and then they fought and fought again. Rings were formed, and within them men pounded each other fiercely. They rolled on the slimy floor and howled and swore and bit and gouged, and the delighted spectators cheered them to redouble their efforts. Out of these fights others sprang into life, and from these still others. The noise was horrible. The wharf became crowded with men eager to know what was going on in the vessel. A tug was sent for, and we were towed into the river, and there the anchors were dropped. Guards ran in on us and beat men with clubbed rifles, and were in turn attacked.

We drove them out of the hold. The hatch at the head of the stairs was closed and locked. The recruits were maddened with whiskey. Dozens of men ran a muck, striking every one they came to, and being struck and kicked and stamped on in return. The ventilation hatches were surrounded by stern-faced sentinels, who gazed into the gloom below and warned us not to try to get out by climbing through the hatches.

Men sprang high in the air and clutched the hatch railings, and had their hands smashed with musket butts. Sentinels paced to and fro along the vessel’s deck, and called loudly to all row-boats to keep off or they would be fired upon. They did not intend that any fresh supplies of whiskey should be brought to us. The prisoners in this floating hell were then told to “go it,” and they went it. We had been searched for arms before we entered the barracks at Albany. The more decent and quiet of us had no means of killing the drunken brutes who pressed on us. There was not a club or a knife or an iron bolt that we could lay our hands to. I fought, and got licked; fought again, and won; and for the third time faced my man, and got knocked stiff in two seconds. It was a scene to make a devil howl with delight.

They reach Alexandria, and then are put on a train to the Union winter camp at Brandy Station. Five more deserters are shot along the way. In the spring, Wilkeson is marched into Virginia. Along the road they pass the bones of unburied dead left from the battle of Chancellorsville.

As we sat silently smoking and listening to the story, an infantry soldier who had, unobserved by us, been prying into the shallow grave he sat on with his bayonet, suddenly rolled a skull on the ground before us, and said in a deep, low voice: “That is what you are all coming to, and some of you will start toward it tomorrow.” It was growing late, and this uncanny remark broke up the group, most of the men going to their regimental camps.

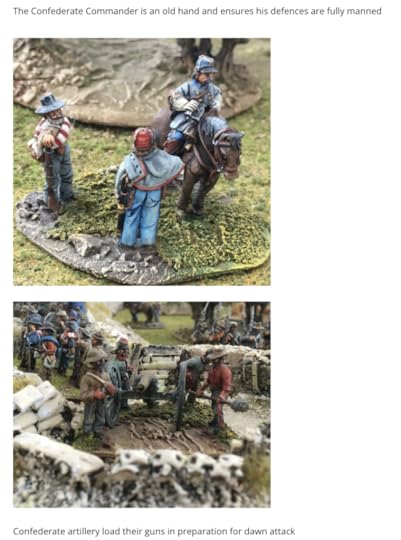

I found this book in a strange way. I was trying to sort out Grant’s Overland Campaign. Here’s an informative video of the strategic level. You can read Grant’s memoirs and many histories and accounts from officers. But what was it like? At Spotsylvania Courthouse, at the Mule Shoe Salient, there was a 22 hour hand to hand scrum, thousands of people killed in like a one square mile bit of earthworks. Did anyone survive to tell about that? In the course of investigating I did find these Australian guys recreating the battle with miniatures:

Their work is amazing.

I’d been playing around with testing various AIs on historical questions. I asked Claude:

What are some notable firsthand account of the fighting at mule shoe salient in the us civil war?

Claude came back with a numbered list of seven sources. Six were officers’ memoirs or official reports, and one was Frank Wilkeson’s “Recollections of a Private Soldier.”

Wilkeson wasn’t actually at the “mule shoe” I don’t think, but close enough. Strangely, on other occasions, Claude has completely made up sources that don’t exist. I go to check them and find they’re nothing, I tell Claude “hey can you give me more information about this, I can’t find it” and Claude says “I apologize, you’re right, I was mistaken.” Weird.

Anyway Frank Wilkeson is very real, his book was reprinted by University of Nebraska Press in 1997. The original title, Recollections of A Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac, is so boring that it possibly caused this book to be ignored. The new title, Turned Inside Out, refers to how the pockets of the dead would all be turned out by battlefield ghouls and robbers of the dead.

At one point Wilkeson actually sees Grant:

One of my comrades spoke to me across the gun, saying: “Grant and Meade are over there,” nodding his head to indicate the direction in which I was to look. I turned my head and saw Grant and Meade sitting on the ground under a large tree. Both of them were watching the fight which was going on in the pasture field. Occasionally they turned their glasses to the distant wood, above which small clouds of white smoke marked the bursting shells and the extent of the battle. Across the woods that lay behind the pasture, and behind the bare ridge that formed the horizon, and well within the Confederate lines, a dense column of dust arose, its head slowly moving to our left. I saw Meade call Grant’s attention to this dust column, which was raised either by a column of Confederate infantry or by a wagon train. We ceased firing, and sat on the ground around the guns watching our general, and the preparations that were being made for another charge.

Grant had a cigar in his mouth. His face was immovable and expressionless.

His eyes lacked lustre.

He sat quietly and watched the scene as though he was an uninterested spectator. Meade was nervous, and his hand constantly sought his face, which it stroked. Staff officers rode furiously up and down the hill carrying orders and information. The infantry below us in the ravine formed for another charge. Then they started on the run for the Confederate earthworks, cheering loudly the while. We sprang to our guns and began firing rapidly over their heads at the edge of the woods. It was a fine display of accurate artillery practice, but, as the Confederates lay behind thick earth-works, and were veterans not to be shaken by shelling the outside of a dirt bank behind which they lay secure, the fire resulted in emptying our limber chests, and in the remarkable discovery that three-inch percussion shells could not be relied upon to perform the work of a steam shovel. Our infantry advanced swiftly, but not with the vim they had displayed a week previous; and when they got within close rifle range of the works, they were struck by a storm of rifle-balls and canister that smashed the front line to flinders. They broke for cover, leaving the ground thickly strewed with dead and dying men. The second line of battle did not attempt to make an assault, but returned to the ravine. Grant’s face never changed its expression. He sat impassive and smoked steadily, and watched the short-lived battle and decided defeat without displaying emotion. Meade betrayed great anxiety. The fight over, the generals arose and walked back to their horses, mounted and rode briskly away, followed by their staff. No troops cheered them. None evinced the slightest enthusiasm.

The enlisted men looked curiously at Grant, and after he had disappeared they talked of him, and of the dead and wounded men who lay in the pasture field; and all of them said just what they thought, as was the wont of American volunteers. This was the only time that I saw either Grant or Meade under fire during the campaign, and then they were with. in range of rifled cannon only.

For a “you are there” quality of the War of the Rebellion – what Wilkeson calls “the suppression of the slaveholders’ revolt” – I’m not sure this book can be matched by anything I’m aware of except Ambrose Bierce and Sam Watkins. The power here is the scenes.

Before noon we came to the village of Bowling Green, where many pretty girls stood at cottage windows or doors, and even as close to the despised Yankees as the garden gates, and looked scornfully at us as we marched through the pretty town to kill their fathers and broth-ers. There was one very attractive girl, black-eyed and curly-haired, and clad in a scanty calico gown, who stood by a well in a house yard. She looked so neat, so fresh, so ladylike and pretty, that I ran through the open gate and asked her if I might fill my canteen with water from the well. And she, the haughty Virginia maiden, refused to notice me. She calmly looked through me and over me, and never by the slightest sign acknowledged my presence; but I filled my canteen, and drank her health. I liked her spirit.

Everybody who knows their Civil War history knows that a key moment was when Grant, after a disastrous first fight with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at the Wilderness, advanced instead of retreating like every previous Army of the Potomac commander. But Wilkeson’s there, man.

” Here we go,” said a Yankee private; “here we go, marching for the Rapidan, and the protection afforded by that river. Now, when we get to the Chancellorsville House, if we turn to the left, we are whipped at least so say Grant and Meade. And if we turn toward the river, the bounty-jumpers will break and run, and there will be a panic.”

“Suppose we turn to the right, what then?”

I asked.

“That will mean fighting, and fighting on the line the Confederates have selected and in-trenched. But it will indicate the purpose of Grant to fight,” he replied.

Then he told me that the news in his Sixth Corps brigade was that Meade had strongly advised Grant to turn back and recross the Rapidan, and that this advice was inspired by the loss of Shaler’s and Seymour’s brigades on the evening of the previous day. This was the first time I heard this rumor, but I heard it fifty times before I slept that night. The enlisted men, one and all, believed it, and I then believed the rumor to be authentic, and I believe it to-day. None of the enlisted men had any confidence in Meade as a tenacious, aggressive fighter. They had seen him allow the Confederates to escape destruction after Get-tysburg, and many of them openly ridiculed him and his alleged military ability.

Grant’s military standing with the enlisted men this day hung on the direction we turned at the Chancellorsville House. If to the left, he was to be rated with Meade and Hooker and Burnside and Pope-the generals who preceded him. At the Chancellorsville House we turned to the right. Instantly all of us heard a sigh of relief. Our spirits rose. We marched free. The men began to sing. The enlisted men understood the flanking movement. That night we were happy.

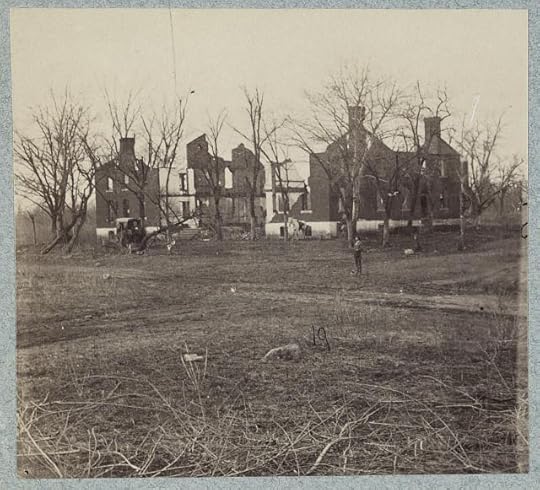

The site of the turn:

as it was:

James McPherson notes in the introduction, Shelby Foote and Bruce Catton took some of the best stuff from Wilkeson.

The most intense chapter of Wilkeson’s book is called “How Men Die In Battle.” You can read it here if you like. Here’s an excerpt (warning: intense, sad):

Near Spottsylvania I saw, as my battery was moving into action, a group of wounded men lying in the shade cast by some large oak trees. All of these men’s faces were gray. They silently looked at us as we marched past them. One wounded man, a blond giant of about forty years, was smoking a short briar-wood pipe. He had a firm grip on the pipe-stem. I asked him what he was doing. “Having my last smoke, young fellow,” he replied. His dauntless blue eyes met mine, and he bravely tried to smile. I saw that he was dying fast. Another of these wounded men was trying to read a letter. He was too weak to hold it, or maybe his sight was clouded. He thrust it unread into the breast pocket of his blouse, and lay back with a moan. This group of wounded men numbered fifteen or twenty. At the time, I thought that all of them were fatally wounded, and that there was no use in the surgeons wasting time on them, when men who could be saved were clamoring for their skillful attention. None of these soldiers cried aloud, none called on wife, or mother, or father. They lay on the ground, pale-faced, and with set jaws, waiting for their end. They moaned and groaned as they suffered, but none of them flunked. When my battery returned from the front, five or six hours afterward, almost all of these men were dead. Long before the campaign was over I concluded that dying soldiers seldom called on those who were dearest to them, seldom conjured their Northern on Southern homes, until they became delirious. Then, when their minds wandered, and fluttered at the approach of freedom, they babbled of their homes. Some were boys again, and were fishing in Northern trout streams. Some were generals leading their men to victory. Some were with their wives and children. Some wandered over their family’s homestead; but all, with rare exceptions, were delirious..

so I guess that’s what it was like.

In looking for info on the original Chancellor House I find this:

In the early 20th century, Susan Chancellor would often stop by for unannounced visits to the re-built house, much to the chagrin of a young girl who lived there with her family. “It was odd that she never knocked,” 89-year-old Hallie Rowley Sale told the Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star in 2003. “It was like she still thought of it as her home. We would hear a door open. And the next thing we knew, Mrs. Chancellor would be leading a group of people through the house.”