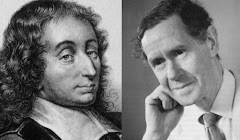

Mackie on Pascal’s Wager

I’ve neverbeen a fan of Pascal’s Wager. But there’sa bit more that one might say for it than is often supposed. For example, the objections J. L. Mackieraises against it in his classic defense of atheism

TheMiracle of Theism

, though important, are not fatal. Let’s take a look at the argument, at Mackie’sobjections, and at how a defender of Pascal might reply to them.

I’ve neverbeen a fan of Pascal’s Wager. But there’sa bit more that one might say for it than is often supposed. For example, the objections J. L. Mackieraises against it in his classic defense of atheism

TheMiracle of Theism

, though important, are not fatal. Let’s take a look at the argument, at Mackie’sobjections, and at how a defender of Pascal might reply to them.The wager

Pascalbegins with the assumption that unaided reason cannot establish one way or theother whether God exists. I think he isquite wrong about that, since Ihold that several of the traditional arguments for God’s existence arecompelling. But suppose, for the sake ofargument, that Pascal is correct. We still,he holds, must “wager” over whether God exists, either betting that he does orbetting that he does not. Yet how canreason decide what bet to make, if it cannot show whether it is theism oratheism that is more likely to be true?

In itssimplest form, Pascal’s argument is this. God either exists or he does not, and you can either bet that he does orbet that he does not. Suppose you betthat he exists, and it turns out that he really does. Then you will enjoy an infinite benefit,eternal life in heaven. But suppose youbet that he exists and it turns out that he does not. You will have been mistaken, but will havesuffered no loss. Of course, whilesomeone who regards a devout and moral life to be of value in itself will agreewith that, a more worldly person would not. He would say that by mistakenly betting that God exists, he woulddeprive himself of worldly pleasures he could have enjoyed. But even if one concedes this, Pascal holds,what one will have lost is still of relatively small value, and certainly offinite value.

Now supposethat one bets that God does not exist, and that in fact he does not. Then, Pascal says, one will enjoy no gainfrom this. Or, even if a worldly personsuggests that he will have gained worldly pleasures from it, this would stillbe a relatively small gain, and certainly a finite gain. But suppose that one bets that God does notexist and it turns out he is wrong – that God does in fact exist. Then,says Pascal, he will suffer an infinite loss. He will have lost out on the infinite reward of eternal life in heaven.

When weconsider this cost-benefit analysis, concludes Pascal, we can see that the onlyrational wager to make is to bet that God exists. Now, Pascal is aware that one cannot simply andsuddenly make oneself believe in God,the way one might make the lights go on by flipping a switch. But since it is reason that tells us to bet on God’s existence, the problem, heconcludes, must be with our passions. These are what prevent belief. And they can be changed by throwing oneselfinto the religious life. Doing so willgradually alter one’s passions, and in this way belief in God can be generated indirectlyeven though it cannot be produced directly by a simple act of will.

Mackie’s critique

Against allthis, Mackie raises two main objections. First, Pascal emphasizes that there is no affront to reason in hisargument, and indeed that wagering that God exists is what reasondictates. But this, says Mackie, is notthe case, for Pascal’s advice to work up belief by way of molding one’spassions amounts to recommending self-deception. Mackie notes that Pascal might respond bysaying that what one is trying to work oneself into is really what amounts to adeeper wisdom or understanding. Butgiven Pascal’s own assumptions, argues Mackie, such a response would beg thequestion. For whether belief in God doesin fact reflect wisdom or understanding about how the world really is isprecisely what Pascal acknowledges to be impossible to establish directly by rationalarguments.

Second, saysMackie, Pascal’s argument can work only if the options we have to choose fromare two, belief that God exists or the absence of such belief. But in fact there are many more options thanthat. We have to choose between Catholicismversus Protestantism, Christianity versus Islam or Hinduism, theism versuspolytheism, and so on. And once we realizethat, we see that Pascal’s argument falls apart. No cost-benefit analysis of the issue isgoing to give us anything like the crisp and clear advice he thinks it does.

Mackie’ssecond criticism overstates the case somewhat. For not every religious view entails that one risks suffering aninfinite loss by rejecting it. Onlyreligions that posit eternal damnation entail that. And for purposes of Pascal’s reasoning, oneneed consider only religions of that kind, which narrows things down. Still, Mackie’s basic point remains thatthere are more than just the two options considered by Pascal (since there ismore than one religion that posits eternal damnation).

Are Mackie’sobjections fatal? It seems to me that thatmay depend on the epistemic situation of the person approaching Pascal’s wagerscenario. Suppose that, as far as youknow, there really are no good rational grounds at all for preferring any onereligion over another. Given theevidence and argumentation available to you, none of them seems like a liveoption, any more than believing in elves or witches does. In this case, Pascal’s Wager seems to have novalue, for the reasons Mackie gives. Itcannot by itself give you a reason to opt for one among the variety of availablereligious options, and the exercise in artificially working up belief in one ofthem would seem to entail irrationally “suppressing one’s critical faculties,”as Mackie puts it (The Miracle of Theism,p. 202). In short, as a strategy forrationally persuading the most unsympathetic sort of agnostic or atheist,Pascal’s Wager appears to fail.

Can it be salvaged?

However,suppose one is in a very different epistemic situation. Suppose, for example, that one is not entirelycertain that the arguments for God’s existence, Jesus’s resurrection, and otherelements of Christian doctrine are correct, but still judges them to be strongand thinks that Christianity is at least very plausible. Suppose that one considers further that amongthese doctrines is the teaching on original sin, according to which ourrational and moral faculties have been damaged in such a way that it is muchless easy for us to see the truth, or to even want to see it, than it wouldhave been had we not suffered original sin’s effects. Then one might judge that it may be thatwhile he regards the evidences for Christianity to be strong, the reason he neverthelessremains uncertain is due to the damage his intellect and will have suffered asa result of original sin.

Hissituation would be comparable to someone who judges that he is suffering fromchronic delusions and hallucinations, like John Nash as portrayed by RussellCrowe in the movie version of A BeautifulMind. Nash has good reasons forholding that some of things he is inclined to believe and thinks that he seesare illusory. Yet he finds he neverthelesscannot help but continue to see these things and be drawn to these paranoid beliefs. Since, overall, the most plausible interpretationof the situation is that these nagging beliefs and experiences are delusional,he decides to refuse to take them seriously and to keep ignoring them untilthey go away, or at least until they have less attraction for him. This is not contrary to reason, but ratherprecisely a way to restore reason to its proper functioning.

Similarly,the potential religious believer in my scenario judges that he has good reasonto think that Christianity really is true, even though he is also nevertheless uncertainabout it. And he also judges that he hasgood reason to suspect that his lingering doubts may be due to the weaknessesof his intellect and will that are among the effects of original sin. Suppose, then, that he appeals to somethinglike Pascal’s Wager as a way of resolving the doubts. He judges that Christianity is plausibleenough that he would suffer little or no loss if he believed in it but turnedout to be mistaken, and little or no benefit if he disbelieved in it and turnedout to be correct. And he also judges itplausible that the potential reward for believing would be infinite, and thepotential loss for disbelief also infinite. So, he wagers that Christianity is true.

Like Nash inA Beautiful Mind, he resolves toignore any nagging doubts to the contrary, throwing himself into the religiouslife and thereby molding his passions and cognitive inclinations until thedoubts go away or at least become less troublesome. And like Nash, he judges that this is in noway contrary to reason, but rather precisely a way of restoring reason to itsproper functioning (given that the doubts are, he suspects, due to thelingering effects of original sin).

In this sortof scenario, then, it’s not that the Wager by itself takes someone from initiallyfinding God’s existence in no way likely, all the way to having a rational beliefin God’s existence. That, as I’ve agreedwith Mackie, is not plausible. Rather,in my imagined scenario, reason has already taken the person up to thethreshold of a solid conviction that God exists, and the Wager simply pusheshim over it.

No doubt,even this attributes to reason a greater efficacy in deciding about theologicalmatters than Pascal himself would have been willing to acknowledge. But, tentatively, I judge it the mostplausible way for the Pascalian to try to defend something like the Wagerargument, at least against Mackie’s objections. (And I don’t claim more for it than that. Naturally, there is a larger literature onthe argument that I do not pretend to have addressed here.)

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 335 followers