Where Do You Stand?

Here’s What I Do on Monday Mornings

Here’s What I Do on Monday MorningsOne day a week, I volunteer at the Raritan Learning Cooperative, in Flemington, New Jersey, to teach a class called, “Where Do You Stand?” The cooperative follows many of ideas laid out in A.S. Neill’s seminal book, Summerhill, and is offered as a support to homeschooled students for whom traditional schooling has not been a good fit. The core staff and a group of volunteer teachers offer a variety of classes, filling up the hours of a school day, but students decide with their advisors what they want to take.

Neill’s theories, which he put into practice in his own school in the 1920s, and which have been embraced by a handful of other schools ever since—notably the Sudbury Valley School in Massachusetts—was that removing compulsion from education would lead to faster and more engaged learning, even if some students took a while to latch on. Neill found this to be true in his own practice: many kids started reading later than they would have in traditional schools, for example, but they quickly caught up with and surpassed their peers.

You can force someone to sit in a chair and comply with directives, Neill thought, but you can’t force them to learn. People learn when they decide something is meaningful to them. What would have felt boring and oppressive when forced becomes important when chosen. As another schooling renegade, John Taylor Gatto once put it, “nothing important can ever really be boring.”

Back to “Where Do You Stand?” I didn’t invent the class; it’s been offered before, though I’ve put a few of my own touches on it. Our big, round table has definitely filled up since the start of the school year, as more kids have decided to drop in and see what we’re doing. The head of the cooperative tells me that some of the students rate it as their favorite class, which is certainly nice to hear.

So, I thought I’d share a little of what we do.

Here’s How it GoesIt begins when someone comes in with a hot topic in mind, or when I suggest a topic (which I do only when I’m met with blank stares and shrugs). It should be an issue about which someone can take a clear Yes/No stand. So far, we’ve covered topics such as: school dress codes; the ethics of animal product testing; the importance of foreign aid; whether the United States should engage in mass deportations; whether a college education should be free; whether the Bible should be taught in schools; and whether a Universal Basic Income is a good idea. Most of these topics were suggested by the kids.

Once we’ve agreed on a topic, we discuss it briefly, just to make sure everyone knows what we’re dealing with. Then I ask the students to get up out of their chairs and show, literally, where they stand. One corner of the room is for those who AGREE; one is for those who DISAGREE; another is for those who DON’T KNOW; and the fourth corner is for those who DON’T CARE (although we’ve yet to find a topic that puts anyone in that corner). We take a few minutes to go around the room and have each student talk about why they’ve chosen that corner and what they think about the issue. I may restate their position to make sure we all understand it; I may ask some clarifying questions. But I don’t challenge them or open the floor to discussion yet. That comes later.

Sometimes, kids will stand along the wall between the AGREE and DISAGREE corners—not quite wanting to commit to DON’T KNOW, but still uncertain about whether they agree or disagree. I always ask them why they’re standing there and why they think it’s different from DON’T KNOW. Most of the time, it’s not that they don’t know; it’s more that they’re going back and forth between the two, or they’re confused.

We go around the room and everyone states their case. Then everyone sits down again and pulls out their phones to do research on the topic. They don’t take notes unless they want to. They do cite sources, if only informally and as part of our discussion. Where kids go looking for information is critical, as we all know, and I want them to think about how they know what they know, or what they think they know.

Early in the year, we had discussions about things like logical fallacies, confirmation bias, and the importance of checking multiple sources. I try, gently, to remind them of these things—especially if there’s evidence of bad argumentation in their research or in the discussion.

Sometimes I ask students to research the topic generally, just to learn more about it. Sometimes I ask them to dig into their opinion for supporting details. Sometimes I encourage them to research the opposite of their opinion, to test and challenge what they think. Sometimes, as we did this week, I ask each of them to look into a different aspect of the issue, because it’s complex and has a lot of moving parts to it.

We take 10 or 15 minutes to do this research, which, admittedly, is far from exhaustive. But it gives the kids a taste of the universe of information out there, and (I hope) it encourages them to look further outside of class. And, to be honest, ten minutes of silent, focused research is a lot for these kids.

After they’ve had some time to dig, we go around the table and share what we’ve learned. I usually ask them where they found their information. Sometimes I push them to dig a little deeper, or I ask them if they’ve really understood what they’ve been reading off their phones. If their understanding is a little wobbly, I try to fill in some of the gaps. I try to be careful not to lecture. That’s not what the class is about.

Everyone says their piece. Then we open it up to general conversation. They’re a lively, curious, and (mostly) talkative bunch, so it’s always an interesting discussion. Sometimes it becomes a serious debate focused on the issue at hand. Sometimes it wanders off down unpredictable side streets and byways. I have no real agenda for any of this, so I’m comfortable letting the conversation go where it will. As before, when I notice gaps in background knowledge or context, I try to do a little backfilling for them.

At the end, everyone votes with their feet again, and we see if anyone has changed their mind. We go around the room, and everyone speaks briefly about why they’re changed their mind, or why they’ve decided to stand firm.

We have had classes when people have moved and shifted quite a bit (their feelings on the importance of foreign aid were once such time). We’ve had times where, no matter what has been said, people stick with their original opinions. That’s fine with me, as long as they’ve really thought about it.

And that’s the class.

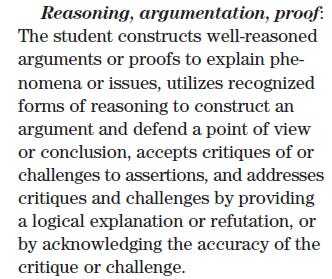

Here’s Why it MattersDavid Conley, director of the Center for Educational Policy Research at the University of Oregon, has long advocated for the importance of research and argumentation in preparing students for the rigors of college work. In his article, “Rethinking College Readiness,” he says:

He goes into more detail here:

One of my favorite books on argumentation, Oh, Yeah?!: Putting Argument to Work Both in School and Out, does a lovely job of systematizing the art of shaping an argument, boiling the process down to three steps:

What do you think?

Why do you think that’s true?

So what?

The “so what?” phrasing is a little aggressive, perhaps, but it’s a critical piece that often gets overlooked by English teachers. (I certainly never gave it the attention it deserved.) Everyone focuses on forming good thesis statements and supporting claims with evidence, but instruction often stops there, which is why so many essays have paragraphs of only a sentence or two, and why so many young writers agonize over what they’re supposed to do next.

The “so what?” piece is officially called the “warrant,” and it may be the most important part of an argument. It’s where the writer or speaker explains why the argument matters—why the reader should care. If X is the claim and Y is the evidence, Z, the warrant, explains why the truth of X is important and meaningful. Very often, it takes some investment of effort in that “warrant” section to really understand why you wanted to make the argument in the first place. The authors of Oh, Yeah?! provide some great examples of arguments where very young students unpack their thinking while trying to explain or justify a stance they’ve taken. Reading the transcript, you can almost see them reaching a little “aha moment” in the process of trying to explain their thinking.

I don’t ask the kids in my class to write essays or even paragraphs, because it’s not what the class is about. They have other opportunities throughout the day or week to focus on their writing, creative and otherwise. And to learn history and science content, if that’s what they’ve chosen to learn. I try to stay focused on the gig I was given: providing an opportunity for kids to talk about things that matter to them and to have their questions and opinions heard and respected by their peers and by an adult.

As I said, I know ten minutes of research isn’t enough for anyone to truly be able to think critically about an issue. I’ll cop to that. Critical thinking can’t happen in a vacuum. You can certainly think emotionally about a topic you know little about [gestures to social media generally], but you can’t think very critically about it. You need to know stuff, and this class is not heavy on the building of content knowledge.

My hope is that the class gives these kids a little taste of something that will develop into a bigger appetite: for questioning, for exploring and investigating, for supporting their opinions with evidence and arguments, and for being willing to challenge their preconceptions and question their biases.

Here’s Why Else it MattersThis is important beyond college readiness. We live in a particularly shouty and stupid age, where the volume and attitude of an argument seem to matter than its factual or rhetorical content. And while that’s entertaining in the gladiatorial arena of social media, it’s not conducive to building a sense of community or making decisions about how to live together. A civics class that replays the old, Schoolhouse Rock video about how a bill becomes a law is great, I guess. The whys and wherefores of our political system are fine and dandy. But we also need to teach kids how people from different backgrounds, with different and sometimes competing ideas and needs, work together to discuss the issues of the day and solve problems for themselves. Expressing your opinions, listening to your neighbors, evaluating the truth and value of what you hear, finding common ground where possible, making compromises where necessary—that’s the core stuff of self-rule, and if we lose that, it won’t really matter which sub-committee is responsible for which bill.

That’s where I stand.

Many thanks to the staff of the Raritan Learning Cooperative for doing the good and hard work of meeting the needs of non-traditional students. It’s a special place. It’s the kind of place where I started my teaching journey, and it’s been great to get back to those roots, even if only for an hour a week.

More thanks and all credit to the fabulous Heather, for pushing me to get away from my computer for an hour and do something useful in the world. And Happy Valentine’s Day!

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers