The Gentleman of Elvas

“Hernando de Soto was the son of an esquire of Xeréz de Badajoz, and went to the Indias of the Ocean sea, belonging to Castile, at the time Pedrárias Dávila was the Governor. He had nothing more than blade and buckler: for his courage and good qualities Pedrárias appointed him to be captain of a troop of horse, and he went by his order with Hernando Pizarro to conquer Peru.” The words are those of a Portuguese knight known only as the Gentleman of Elvas, a witness to and survivor of the long and agonizing disaster that was de Soto’s Florida enterprise.

The Gentleman of Elvas is one of several members of that expedition whose accounts have come down to us, and his was the first to be published, in 1557.

An English translation by the geographer Richard Hakluyt appeared in 1609, and there were other English editions in 1611 and 1686, as well as Spanish and French versions in the seventeenth century; so there was never any question of the work’s inaccessibility. Another account, by Luis Hernández de Biedma, remained unpublished until 1857, while that of de Soto’s secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, has never appeared except in severely abridged form. The most extensive work on the expedition, known as The Florida of the Inca, was written by a man born just a month before de Soto first set foot in Florida: Garcilaso de la Vega, known as “the Inca” because his mother, Chimpa Ocllo, had been a princess of Peru. (His father, Don Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega Vargas, had seen action with the Pizarros during the Spanish conquest of Peru.) Garcilaso, an attractive and complex figure who spent most of his life in Spain but who was fiercely proud of his royal Inca ancestry, published his book on de Soto at Lisbon in 1605. His chief sources were the oral recollections of an anonymous Spaniard who had marched with de Soto, and the crude manuscripts of two other eyewitnesses, Juan Coles and Alonso de Carmona.

From these Garcilaso wove a lengthy and vivid history, long thought to be largely fantastic, but now recognized as a trustworthy if somewhat romantic narrative. Its chief concern to us is the detailed descriptions it provides of Indian mounds of the Southeast.

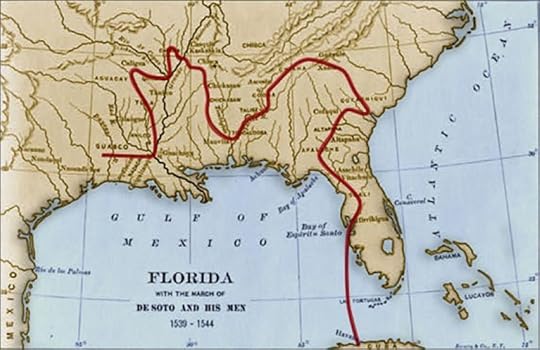

De Soto had served with distinction in Peru. He fought bravely against the Incas, and acted as a moderating influence against some of the worst excesses of his fellow conquerors. The darkest action of that conquest-the murder of Atahuallpa, the Inca Emperor-took place without de Soto’s knowledge and despite his advice to treat the Inca courteously. He shared in the fabulous booty of Peru and in 1537 came home to Spain as one of the wealthies men in the realm. Seeking some tract of the New World that he could govern, he applied to the Spanish king, Charles V, for the region now known as Ecuador and Colombia. But Charles offered him instead the governorship of the vaguely defined territory of “Florida,” which had lapsed upon the disappearance of Pánfilo de Narvez. By the terms of a charter drawn up on April 20, 1537, de Soto obligated himself to furnish at least 500 men and to equip and supply them for a minimum of eighteen months.

In return, he would be made Governor of Cuba, and upon the conquest of Florida would have the rank of Adelantado of Florida, with a domain covering any two hundred leagues of the coast he chose. There he hoped to carve out a principality for himself as magnificent as that obtained by Cortés in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru.

In the midst of de Soto’s preparations, Cabeza de Vaca turned up in Mexico, and at last revealed the fate of Narvez’ expedition. De Soto invited Cabeza de Vaca to join his own party, but he had had enough of North America for a while, and went toward Brazil instead. De Soto collected men, sailed to Cuba, and recruited more men there. His reputation had preceded him from Peru; he was thought to have the Midas touch, and volunteers hastened to join him. He gathered 622 men in all, including a Greek engineer, an English longbowman, two Genoese, and four “dark men” from Africa. In April of 1539 they departed for Florida.

The expedition entered Tampa Bay a month later, and on May 30 de Soto’s soldiers began going ashore. Their object was to find a new kingdom as rich at Atahuallpa’s, and it seems strange that they would have begun the quest in the same country where Narváez had found only hardship and death.

From Mound Builders of Ancient America: Archaeology of a Myth (1968) by Robert Silverberg, who writes more vividly on de Soto than many a de Soto specialist. You can read all of the Gentleman of Elvas account here, it ain’t exactly Tom Clancy. Silberberg picks up:

had de Soto been gifted with second sight, he would have sounded the order for withdrawal at that moment, put his men back on board the ships, and returned to Spain to fondle his gold for the rest of his days. Thus he would have avoided the torments of a relentless, profitless, terrible march over 350,000 square miles of unexplored territory, and would have spared himself the early grave he found by the banks of the Mississippi. This was no land for conquerors. But a stroke of bad luck, in the guise of seeming fortune, drew de Soto remorselessly onward to doom. His scouts, while fighting off the Indian ambush, had been about to strike one naked Indian dead when he began to cry in halting Spanish, “Do not kill me, cavalier! I am a Christian!” He was Juan Ortiz of Seville, a marooned member of the Narvez expedition, who, since 1528, had lived among the Indians, adopting their customs, their language, and their garb. He could barely speak Spanish now, and he found the close-fitting Spanish clothes so uncomfortable that he went about de Soto’s camp in a long, loose linen wrap. He seemed precisely what de Soto needed: an interpreter, a guide to the undiscovered country that lay ahead.

Unhappily, Ortiz knew nothing of the country more than fifty miles from his own village, and each village seemed to speak a different language.

Nevertheless, the Spaniards proceeded north along Narvez’ route, looking for golden cities. Ortiz spoke to the Indians where he could and arranged peaceful passage through their territory. Where he could not communicate with them, the Spaniards employed cruelty to win their way—a cruelty that quickly became habitual and mechanical. The Indians were terrified of the Spaniards’ horses, for they had never seen such beasts before. With the Spaniards there came also packs of huge dogs, wolfhounds of ferocious mien.

Wolfhounds of ferocious mien.

That illustration, by Herb Roe, I find on de Soto’s Wikipedia page. Here’s a Herb Roe evocation of the Kincaid Site in Illinois:

Here is Herb Roe’s website.

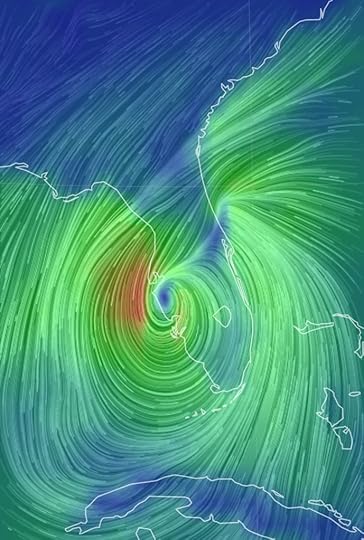

Tampa’s on my mind today as its about the get wrecked by Hurricane Milton.

Prayers up for the Cigar City.

Source for that map of de Soto expedition is the Florida Historical Society. Winds tracker from earth.nullschool.net.

Related matters: Cahokia.