To Hell and Back

There are few true-crime stories as terrifying as the infamous serial killings committed by a figure known only as Jack the Ripper. Amidst decades of speculation, to this day the killer’s identity has never been definitively discovered. “Jack” went on a macabre crime spree in one of the most populated cities in the world yet was never caught – that we know of. That cloud of uncertainty is what inspired Jack’s appearance in my novels, tied in with the supernatural, of course.

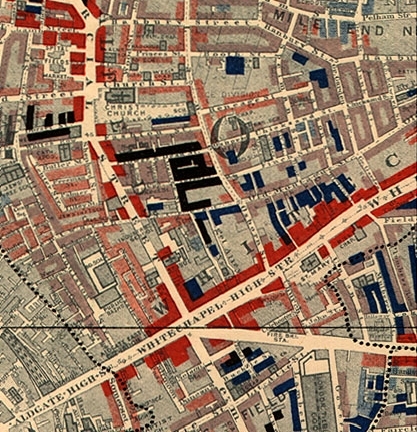

Victorian London was a far different place than it is now. By 1825 London was the largest city in the world, crammed with over five million people. While it was a global financial capital with great wealth, it was also a warren of crowded slums and extreme poverty. The very wealthy lived in luxury in the upper-class West End, while their opposites lived in squalor in the East End.

By Charles Booth – http://www.umich.edu/~risotto/maxzooms/ne/nej56.html (cropped). Original: Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People. Volume 1: East London (London: Macmillan, 1889)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9361611

By Charles Booth – http://www.umich.edu/~risotto/maxzooms/ne/nej56.html (cropped). Original: Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People. Volume 1: East London (London: Macmillan, 1889)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9361611A sizeable immigrant community settled in the East End, including the notorious Whitechapel and Spitalfields districts. Whitechapel housed a lot of factories and foundries, tanneries and slaughterhouses, and other industries that fed the city’s growing demands. People worked in appalling conditions for little pay, most of them largely destitute and looking for any way to support themselves and possibly a family.

One of the theatre actors of the time, Jacob Adler, wrote: “The further we penetrated into this Whitechapel, the more our hearts sank. Was this London? Never in Russia, never later in the worst slums of New York, were we to see such poverty as in the London of the 1880s.”

As a result, many women turned to prostitution. Leading up to the Ripper murders, there were an estimated 1,200 female sex workers in the area.

Petty crime was rampant – pickpocketing and/or garrotting (mugging with strangulation) in particular. There was also a lot of domestic violence that remained largely unreported. In 1863 Parliament introduced floggings to punish violent robbery, while serious criminals were either sentenced to hard labour or getting shipped off to Australia. Murderers were hanged.

Whitechapel, by 1888, had become a crush of people – around 80,000 inhabitants all struggling to make it through another day. Approximately 8,500 people tried to get some sleep at night in the 233 lodging-houses, where, for fourpence they could lie down in a coffin-shaped wooden box, called a coffin bed, and try to stay warm under a tarp cloth. If they couldn’t afford that, for two pence they could rest on a lean-to rope. Over fifty percent of children in the parish died before they were five years old.

Alcoholism and pervasive violence gave rise to waves of social disturbance. The relatively new Metropolitan Police Service, created less than 60 years before, struggled to cope with outbreaks of racism, antisemitism and general antipathy towards the many immigrants. Whitechapel soon developed a reputation as a den of immorality.

Into this fraught atmosphere, gruesome murders made a regular appearance, well before Jack took up the blade. From 1873-4, and again in May 1887 and September 1888, a series of dismembered body parts (torsos, thighs, heads, organs and more) washed up on the banks of the Thames and terrified Londoners for months. They were dubbed the Thames Torso Murders, and the perpetrator was never caught.

There were so many murders, amid the thick fogs of Victorian London that spewed from factories and chimney pots, that when a new spate began in 1888, the police had trouble assigning which belonged to the terrifying killer eventually called Jack the Ripper.

As the Thames flowed through the city, its mists joined the residential and industrial smogs to blanket the narrow, winding streets. At times, travel from place to place was almost impossible, often for days at a time. Street urchins called ‘linklighters’ would carry homemade torches and offer to guide people through the yellow-grey, or even black, miasma for a fee – sometimes to the cosh of a mugger lurking in the darkness.

Imagine now that you’re a ‘working woman’, haunting the streets to make a little money. Dusk has fallen and a fog has rolled in. It’s your last chance to earn enough for some food and a night’s rest, and you can’t afford to be choosy with your customers. Appearing out of the foul-smelling gloom, a carriage pulls up, its horses snorting. The person inside must have enough money to afford such a conveyance, so they’re a good prospect – maybe more than you’re earned all the rest of the day. The door opens, and you step up. Whoever has invited you in will be the last person you’ll ever lay eyes on, screaming with your final breaths.

Such is the image we have of the horrifying murders committed by history’s most infamous serial killer. But the identity of the murderer was never discovered – or at least made public.

The first page of the “Dear Boss” letter, dated 25 September 1888, By Jack the Ripper – National Archives MEPO 3/142, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=249916

The first page of the “Dear Boss” letter, dated 25 September 1888, By Jack the Ripper – National Archives MEPO 3/142, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=249916Ever since 1888, both professional and amateur detectives have tried to puzzle out who Jack really was. Whoever he was, and I don’t think we’re even sure of the actual gender, he received his moniker fro a message sent to the Central News Agency of London on September 25 of that year. It was two pages long, written in red ink:

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck. Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha

The police had received many hoax letters from the supposed killer, and at first the Dear Boss letter was thought to be another – until the body of Catherine Eddowes was discovered in Mitre Square on September 30, with part of the right ear severed. After that, a copy of the letter, along with that of a subsequent postcard on October 1 from “Saucy Jack”, saying that he hadn’t had time to complete the ear job, were widely circulated in the hopes that someone would recognize the handwriting. No one did, but the “Jack” name stuck.

Interestingly, in 1931, a journalist named Fred Best from The Star newspaper supposedly confessed that he and one of his colleagues had written both the letter and the postcard (and other similar hoax messages) in order to foment public interest in the case and boost the sales of the paper. If that was true, did that mean that the actual killer read the letter and decided to emulate the ear-mutilation promised in it? Or did the journalists even collude with their muse?

We’ll never know, it seems. One of the most unnerving aspects of the killings is how the murderer was able to commit extensive and time-consuming murders and then vanish into the bowels of such a well-populated city without discovery. They may have had help, especially if you believe one of the theories that Jack was actually the deranged Prince Albert Victor, the son of King Edward VII.

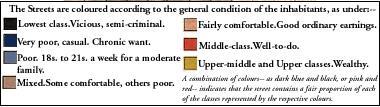

Mutilated bodies continued to pile up in the loathsome streets of London. The first of the five murders specifically attributed to the Ripper occurred in August, in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel. Mary Ann Nichols had last been seen alive walking in the direction of Whitechapel Road only about an hour before her body was discovered.

A week later, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street in Spitalfields. Like Nichols, her throat was severed by two deep cuts, and further mutilations had been inflicted on her.

At Chapman’s inquest, someone said they’d seen her standing outside the building just half an hour before, with a “shabby-genteel”, dark-haired man wearing a dark overcoat and a deer-stalker hat (the kind that Sherlock Holmes famously favoured). He had apparently asked Chapman, “Will you?”, and she’d said, “Yes.” Perhaps an invitation to share her favours.

8 September 1888 edition of the Penny Illustrated Paper depicting the discovery of the body of the first canonical Ripper victim, Mary Ann Nichols By Unknown author – https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6389700, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79437511

8 September 1888 edition of the Penny Illustrated Paper depicting the discovery of the body of the first canonical Ripper victim, Mary Ann Nichols By Unknown author – https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6389700, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79437511 In the early hours of September 30 there were two murders, those of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes. Elizabeth’s body didn’t have any mutilations below her neck, so it was uncertain whether it wasn’t the same killer, or if he/she/they had been interrupted before being able to finish. Several witnesses reported seeing her in a man’s company, but the descriptions were all different, making any identification impossible.

Catherine Eddowes, unfortunately, suffered the full treatment. Her body was found in a corner of Mitre Square, a mere three-quarters of an hour after Stride’s body was discovered. The killer had worked fast to find another victim. Eddowes’ mutilations were vicious, from horrific cuts on her face and the characteristic severing of the throat down to her bowels and reproductive organs. The murders of these two women became known as the “double event”.

A chalk inscription upon a wall after Eddowes’ murder, above where her bloodied apron was found, became famous: “The Juwes are The men That Will not be Blamed for nothing.” Such graffiti were commonplace in Whitechapel, and, fearing that it might incite antisemitic riots, Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren ordered the writing washed away.

On October 16, the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, a group of local civilian volunteers formed by sixteen tradesmen from the Whitechapel and Spitalfields districts worried that the killings were affecting businesses in the area, received a macabre gift. A letter captioned “From Hell” at the top arrived in a box along with the left half of a human kidney. In the letter, the writer claimed that he “fried and ate” the other half. Catherine Eddowes’ left kidney had been cut out; the one received by the Vigilance Committee was examined and found to be human, but nothing else could be determined. The writer signed off with “catch me if you can”.

A photographic copy of the now-lost “From Hell” letter, postmarked 15 October 1888, by Unknown author (credited to Jack the Ripper) – Original in the Records of Metropolitan Police Service, National Archives, MEPO 3/142; this facsimile from http://www.casebook.org/ripper_letters/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=249871

A photographic copy of the now-lost “From Hell” letter, postmarked 15 October 1888, by Unknown author (credited to Jack the Ripper) – Original in the Records of Metropolitan Police Service, National Archives, MEPO 3/142; this facsimile from http://www.casebook.org/ripper_letters/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=249871 The final ‘official’ victim was Mary Jane Kelly, and the most savagely destroyed. Her body was discovered lying on the bed in her room in Spitalfields, on the morning of November 9. Even her face had been “hacked beyond all recognition”, and body parts removed to decorate the room with. The heart was missing from the crime scene, a curious detail. Ashes in her fireplace seemed to suggest that the killer had burned some things to light the room for his work, hot enough melt the solder between a kettle and its spout, causing the spout to fall into the grate. You can see the police photo of the body on Wikipedia if you have the stomach for it.

All of the murders were incredibly brutal, as if the Ripper acted out of great anger, great obsession, or, more disturbingly, great pleasure. The victims were all prostitutes; whether the Ripper targeted them for their profession, or their easy access, is unknown.

Then the murders ceased, all of a sudden. There were other possible similar murders in various locations, but no concrete connection to the famous five was ever established.

Most of the police files relating to the investigation were destroyed in the Blitz in WW2, but the surviving files show that the investigation was extensive. Forensic material from the crime scenes was collected and examined, house-to-house inquiries were made throughout Whitechapel, over 2000 interviews were conducted and more than 300 people were investigated. After the “double murder”, the Commissioner of the City Police offered a reward of £500 for the arrest of the Ripper.

Never solved, the file was officially closed in 1892, and like all unsolved mysteries, it continues to haunt the public imagination. The list of suspects is substantial, including Queen Victoria’s personal physician, William Gull. At the time, Inspector Macnaghten of Scotland Yard believed that a barrister named Montague John Druitt was the killer; the sole ‘evidence’ seems to have been his unfortunately turning up drowned in the Thames shortly after the murders ceased.

London dockworkers were under suspicion because they worked near Whitechapel. A scrap metal merchant named James Maybrick allegedly left a diary confessing to the murders, which he’d committed on a rampage after discovering his wife had been unfaithful. The diary stated that: “I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell, what love can do to a gentle man born. Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

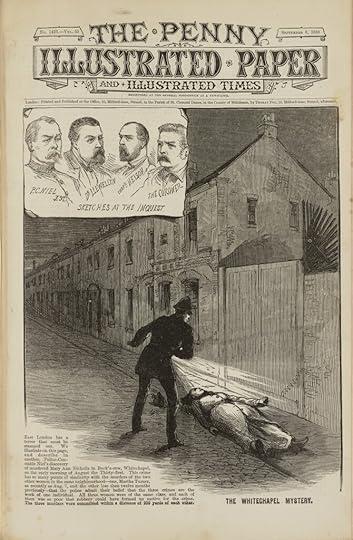

There have been numerous theories as to the Ripper’s true identity – even the writer Lewis Carroll, of Alice in Wonderland fame, has come under some weird scrutiny in modern times.

First edition (publ. Gemini Press) By https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=30349099103, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61183909

First edition (publ. Gemini Press) By https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=30349099103, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61183909Carroll was sent, at the age of 12, to a boarding school, and wrote home about how unhappy he was there. In 1996 a writer named Richard Wallace decided that Carroll and his colleague Thomas Vere Bayne were responsible for the Jack the Ripper murders. He based it on three things: that early schoolboy upset, Carroll’s fondness for wordplay, and the fact that Carroll would have been working on two of his works, one of which was The Nursery “Alice”, an adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland for younger readers, during the Ripper murders.

Wallace’s notion was that, during his time at the boarding school, Carroll was physically abused at the school and had a psychotic break that stayed with him. Carroll then apparently took it out as an adult on the women of Whitechapel and hid messages to that effect in his books, as well as some of his letters.

Here’s a sample of Wallace’s deductions: a sentence to Carroll’s brother Skeffington, “My Dear Skeff: Roar not lest thou be abolished”, was believed to actually read (letters rearranged): “Ask mother about the red lion: safer boys fled.” The “red lion” was a game played at Carroll’s boarding school, one that Wallace suspects was sexual in nature and left Carroll burning with fury toward his mother and father, who had sent him to the school, and toward society at large.

Wallace declared that in The Nursery Alice, Carroll confessed to the gruesome murders. He ‘deciphered’ one of the passages as:

“If I find one street whore, you know what will happen! ‘Twill be off with her head!”

There were a lot more stretched ‘confessions’, in Wallace’s mind. The fact that the writing of Carroll’s diary entries didn’t match the Ripper’s letters to newspapers didn’t discourage him—someone could have written them on his behalf.

After Wallace’s research was discussed in a 1996 issue of Harper’s magazine, two readers took the time to point out that the opening paragraph of the book:

This is my story of Jack the Ripper, the man behind Britain’s worst unsolved murders. It is a story that points to the unlikeliest of suspects: a man who wrote children’s stories. That man is Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, author of such beloved books as Alice in Wonderland.

could be reordered to offer his own confession:

The truth is this: I, Richard Wallace, stabbed and killed a muted Nicole Brown in cold blood, severing her throat with my trusty shiv’s strokes. I set up Orenthal James Simpson, who is utterly innocent of this murder. P.S. I also wrote Shakespeare’s sonnets, and a lot of Francis Bacon’s works too.

(Source: On the time Lewis Carroll was accused of being Jack the Ripper.)

Wallace never responded – indeed, how could he? His spurious theory had just been blown out of the water, not that it was ever taken very seriously anyway.

In 1888, the police believed that the Ripper was living in Whitechapel himself, with intimate knowledge of the area’s back alleys and hiding places that allowed him to quickly disappear after each murder. It was a sound-enough theory, but impossible to track; the population of the Whitechapel district was largely transient and often used aliases. It would have been easy for someone to fade into the background.

Several theorists believe that “Jack the Ripper” was actually several killers, either as some kind of cabal, or just unconnected nutbars. There was also a theory that the Ripper was a woman, not a man – possibly Mary Pearcey, who’d used a method similar to the Ripper’s to murder of her lover’s wife and child. She was convicted and hanged in 1890.

Police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer’s character and surgical knowledge. It’s the earliest known offender profile in criminal history. Bond didn’t think that the murderer had any kind of special anatomical or scientific knowledge, or even “the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer”. He believed that the Ripper must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to “periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania”, and that “the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease but I do not think either hypothesis is likely”.

Although there was no evidence of sexual contact with any of the victims, some psychologists suggest that the ‘penetration’ with a knife and the sexually degrading positions the women were left in indicates sexual pleasure from the attacks.

Modern DNA analysis on the Ripper letters has been inconclusive, as they’ve been handled many times and are too contaminated. There’s no other concrete surviving evidence to apply forensics to.

There are far too many suspects, both at the time and over time, to include in this blog. I don’t believe we’ll ever know the identity of Jack the Ripper, unless something remarkable from the past comes to light.

Personally, I love the suggestion in the episode of the original Star Trek series called Wolf in the Fold. (No spoilers here: watch the very eerie episode to see for yourself.)

The From Hell letter inspired me to imagine my own theory of what could turn a man into such a monster, and you can read that excerpt from Book 1: Through the Monster-glass, on this site on the Bonus Materials page (all materials are under my copyright and may not be distributed or re-used without contacting me for permission). Let me know what you think as we kick off this spine-chilling month; that’s not the final reference to the Ripper killer in my trilogy.