The Great Art of Light and Shadow

Phantasmagoria and Magic Lanterns

“Fear does not have any special power unless you empower it by submitting to it.”

Les Brown

Terrifying audiences isn’t a modern invention. There’s something about shared horror that has captivated people for several centuries, huddling in a darkened room waiting to be scared out of our wits.

In the 1600s, projectors called Magic Lanterns were invented. They used a concave mirror behind a light source, which would concentrate and direct the light through a transparent slide with an image painted on it. There would then be a lens at the front that was used to focus the image and enlarge it onto some form of projection screen, like a white wall (which people still use today in a pinch). And just like more modern projectors (I still have one), the slide had to be inserted upside down because the lens would invert the image as it passed through.

The Magic Lantern Shows offered horror for a different purpose to begin with. Apparitions of ghosts, witches, devils and demons were used in Europe by the clergy (and, of course, by con men even then), to make the viewers believe they were really seeing the creatures appear, terrifying them in to turning to God (or whatever the con men were peddling).

Originally the pictures were hand painted with black paint, but transparent colors came into vogue, set onto a black-painted background to block out other light so the images could be projected as if they were floating in mid-air.

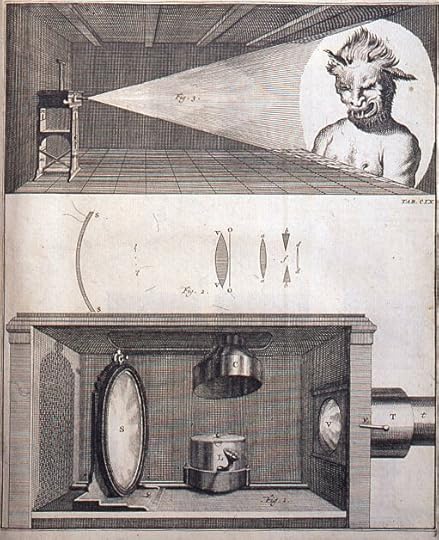

A page of Willem ‘s Gravesande’s 1720 book Physices Elementa Mathematica with Jan van Musschenbroek’s magic lantern projecting a monster. The depicted lantern is one of the oldest known preserved examples, and is in the collection of Museum Boerhaave, Leiden; by Jacob ‘s Gravesande – scan from Physices Elementa Mathematica, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50615645

A page of Willem ‘s Gravesande’s 1720 book Physices Elementa Mathematica with Jan van Musschenbroek’s magic lantern projecting a monster. The depicted lantern is one of the oldest known preserved examples, and is in the collection of Museum Boerhaave, Leiden; by Jacob ‘s Gravesande – scan from Physices Elementa Mathematica, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50615645Oil lamps and candles were the first light sources, but they weren’t bright enough to produce good images. In the late 1700s the Argand lamp was invented, which used a wick surrounded by a glass chimney, burning oil from seals, whales, olives and other vegetables more efficiently and brighter.

Limelight, which used a flame directed by a blowpipe at a cylinder of quicklime, a chemical compound made by burning organic materials like seashells in a kiln, was invented in the 1820s. Such lamps were able to emit a much brighter light, and limelighting was the standard in Victorian theatres for many years. It was prone to starting fires, though, and in the 1860s the electric arc lamp came along that was much safer to use.

The shows were so popular that by the 19th century, itinerant projectionists would travel around with their magic lanterns putting on shows in towns and villages all over the countryside. They had a large stock of slides, with extra sections that could rotate across the main plate to create some special effects. One of the most famous shows was the Rat-swallower, where rats would climb up a bed and crawl into the mouth of a man sleeping in it. You can see a brief clip of this on the Kent Museum of the Moving Image Facebook page.

In the mid-18th century, a coffee shop owner in Leipzig, Germany named Johann Schröpfer converted an old billiards room into a theatre and began offering ‘séances’. His surprised audience didn’t know what was coming. They were assailed by a show that included eerie music, projections on smoke and sound effects, incense, drugs, even electric shocks.

Schröpfer was an interesting person. He claimed to be able to communicate with the spirit world, and that he was the only person who knew the real secrets of Masonry. He reportedly stole some “magical” documents from the Masons, then learned more magic from a German merchant. Schröpfer began performing ‘necromantic’ works not long after that, wherein his collection of followers would have to fast for 24 hours, after which they were served punch and some food that was likely drugged. They would then be dramatically led at midnight, already in an altered state of mind, into a darkened room with an altar draped in black. Schröpfer would appear in a robe and lead them through a series of rituals during which they had to remain sitting at a table or ‘face terrible dangers’. He would typically raise three different spirits, accompanied by uncanny noises. These ghosts could answer his questions, in a hollow-sounding voice.

Actors playing the ghosts, and special effects created with hidden speaking tubes, eerie sounds from a glass harmonica, thunder, and projections onto wavering smoke as opposed to a solid wall, all made the shows so convincing that people believed the spirits were real. Schröpfer was a clever showman, and his performances became so popular that within a few years he’d created an entirely new career for himself. These types of spirit shows became known as “Phantasmagoria”.

Phantasmagoria projectors were mobile, allowing the images to be shown on various types of screens and giving the unnerving illusion of movement. They often used rear projection to make the effect even more mysterious. Multiple projectors allowed a projectionist to switch different images quickly, creating a kind of horror movie filled with ghosts and demons. Many of the phantasmagoria showmen were a combination of scientist and magician, combining technical skills and imagination into drawing the audiences into a complete make-believe world for the duration.

The most famous of them was a Belgian inventor and physicist, Etienne-Gaspard Robert, who became known by his stage name, Etienne Robertson. He’d spent some of his youth in Paris during the height of the French Revolution, and after perfecting his elaborate illusions, returned to Paris to use the macabre atmosphere still permeating the city post-Revolution for ambience. He would stage his shows in an abandoned crypt, letting the natural eeriness inside the tomb set the stage, and then terrify his audiences with all the tricks up his sleeve.

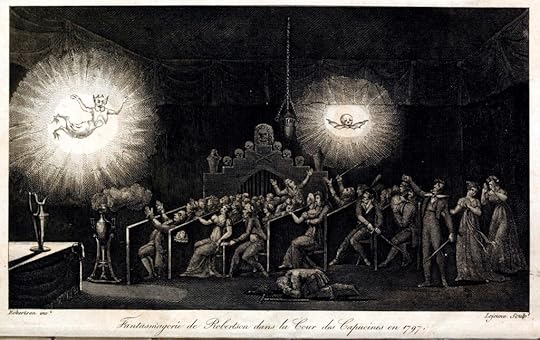

Robertson’s phantasmagoria, Paris, 1797; by Etienne Gaspard Robertson – Internet Archive, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58344135

Robertson’s phantasmagoria, Paris, 1797; by Etienne Gaspard Robertson – Internet Archive, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58344135His philosophy was that “I am only satisfied if my spectators, shivering and shuddering, raise their hands or cover their eyes out of fear of ghosts and devils dashing towards them; if even the most indiscreet among them run into the arms of a skeleton.” After his death, Robertson was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris in a three-storey tomb replete with macabre imagery.

In 1774, the inventor of phantasmagoria, Johann Schröpfer, committed suicide, apparently delusional about his own creations. Perhaps a cautionary tale

By the 19th century, phantasmagoria shows were big hits in London and throughout the UK, then expanding to the U.S. As technology improved, of course, the old tricks didn’t work as well and the art form eventually dwindled. However, it inspired writer Lewis Carroll in his poems as well as several French painters. Disney attractions like The Haunted Mansion have also used similar special effects, and modern-day film-makers use the same sensory and psychological techniques to continue to scare the pants off millions of satisfied movie-goers, still in darkened rooms where you can’t see what might be sneaking up on you from behind.

If you’d like to get a 2-D sense of what one of these shows was like, the Museu del Cinema presents one on YouTube. Fantasmagoria Llanterna Màgica. Museu del Cinema. In full performance, surrounded by the sights and spine-chilling sounds, they must have been overwhelming. Frankly, I’d love to have seen one of those shows – they sound amazing. In a day and age when CGI and all of the Hollywood tricks weren’t even the gleam in someone’s eye, an atmosphere of sheer fantasy and dread was summoned with a projector and a few creative effects. Millions of houses do it every Halloween, just for the fun of it.

“Figures rise, like phantoms, pale in the dusky lamp light…”

Thomas Carlyle, French Revolution