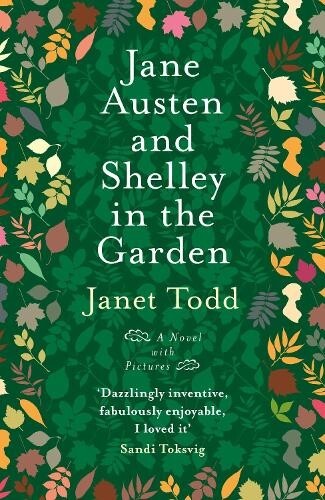

From the forthcoming book Living with Jane Austen, by Janet Todd

To celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth, I wrote Living with Jane Austen for Cambridge University Press. Part Austen commentary and part academic memoir, it aims to show why Austen matters to us now and how our understanding of her work changes at different cultural moments. As I wrote new chapters or revisited old talks, I was repeatedly struck by how much sterner and colder Sense and Sensibility is compared with the other novels.

(From Sarah: This is the twenty-eighth guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility,” which began on June 20th and will come to an end tomorrow. You can find all the contributions to the blog series here . I hope you’ll join the conversations about S&S in the comments here and on social media: #senseandsensibilitysummer. Thanks for celebrating Jane Austen’s first published novel with us!)

Reading with Mary Wollstonecraft

Throughout my book I shadowed Jane Austen with another of my literary heroines (whose biography I wrote many years ago), Mary Wollstonecraft. Before she composed her great Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she reviewed novels for the new radical journal, the Analytical Review. In these pieces she inveighed against fiction, usually “by a Lady,” aimed at susceptible female readers who were persuaded to believe in the unrealistic fantasy of combined power, riches, large house, and fulfilled desire all delivered to them by a handsome young man. Seeing Austen through Wollstonecraft’s imagined eyes, I reacted more severely than I might otherwise have done to Pride and Prejudice as a kind of “property porn.” Gleefully Elizabeth imagines herself “mistress” of Pemberley. Wollstonecraft exclaimed, “Oh why is virtue always to be rewarded with a coach and six”—or a great estate? She called such a romantic denouement a “whipped syllabub” (a common dismissive term occurring also in Austen’s writing). She might have damned Pride and Prejudice had she not read closely this extraordinary work.

By contrast, in Sense and Sensibility there’s no question of Elinor becoming mistress of a great estate, just an indifferent parsonage, and she eschews the fantasy of property. Hers is a more difficult desire: “I will be mistress of myself” (Volume 3, Chapter 12). In The Rights of Woman Wollstonecraft held firmly to the need for her sex to know themselves, to be rational, to judge with consideration—as Elinor supremely does—and not to believe, with Marianne, that if something feels good, it’s right. But if a great estate is not required for well-being, a modest competence is. Elinor consoles Marianne for the loss of desirable Willoughby by noting: “Had you married, you must have been always poor” (Volume 3, Chapter 11). In Mansfield Park the youngest Ward sister is romantic: she weds Lieutenant Price of the marines with no consideration of income and is reduced to relative poverty.

Sickness

Because of the personal element in my book (and given my age and array of ailments), I spent much time on mental and physical illness—nerves, colds, bile and so on. Austen often comments on the confusion of mental and physical that so worried the period. One example is the comic proposition of salving a lovelorn heart with wine. In Mansfield Park Edmund presses Madeira on headachy Fanny whose problem is thwarted desire for himself. In Sense and Sensibility Mrs. Jennings suggests expensive Constantia wine (once used for her dead husband’s “cholicky gout”) to soothe Marianne’s lovesickness. A little foolish perhaps, but, when Marianne has a respite during her severe self-inflicted illness, Elinor too administers “cordials.” Elinor and Mrs. Jennings have the support of the early medical writer George Cheyne who, in his Essay on Health and Long Life, wrote that for women of “weak nerves . . . the only Remedy for them, is drinking Bristol Water and red Wine, with a low and light Diet.”

Ailments can of course be primarily physical and they’re most salient in Sense and Sensibility, especially in the inset story of the two Elizas related in different tone from the dramatized part of the novel. This describes Colonel Brandon’s beloved suffering a life of misery and degradation from an initial fall into “vice,” then contracting consumption (tuberculosis), then dying. When (in rather unnerving echo) young Marianne falls ill after what starts as a chill from sitting in wet stockings, some of the earlier anxiety touches this later sickness. She ends with a dangerous “putrid fever.” Her illness becomes a rite of passage to reform:

My illness . . . had been entirely brought on by myself. . . . Had I died,—it would have been self-destruction . . . I wonder at my recovery,—wonder that the very eagerness of my desire to live, to have time for atonement to my God, and to you all, did not kill me at once. (Volume 3, Chapter 10)

Marianne changes within a Christian framework. So too does Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park: “He was the better for ever for his illness. . . . He became what he ought to be” (Volume 3, Chapter 17). Although there’s no mention of God in the later passage, the complete reformation occurs in a novel tilting a little towards evangelical Christianity. Sudden conversion is rare in Austen and most peripheral characters are like Lydia in Pride and Prejudice—following her brush with disaster: “Lydia was Lydia still” (Volume 3, Chapter 9). Marianne’s near-death experience invokes God; it teaches her right thinking and directs her to a more sensible, if less dashing, choice of life partner. But, unlike Tom Bertram’s, her good resolutions are treated with some irony: they are characteristically extreme.

After Sense and Sensibility, Austen will not be so melodramatic again and perhaps there’s a mocking self-reference to this earlier novel in Emma. Always on the lookout for threats to the body, finicky Mr. Woodhouse is troubled about wet stockings. He fusses over Jane Fairfax and her rainy walks to the post office: “My dear, did you change your stockings?” he enquires (Volume 2, Chapter 16).

Weather

As I moved through topics and decades of criticism I touched on language, allusions, social embarrassment, unruly bodies—and death. I discussed nature too, not in the wonderfully detailed way Hazel Jones has done in a recent blog post for this series, but mainly as spectacle and prompt for reverie. Above all I treated it through “weather.”

Weather is featured in every Austen novel but my favourite intrusion is Lady Middleton’s comment on rain in Sense and Sensibility. It spares Elinor further teasing about a lover with the initial “F”:

Most grateful did Elinor feel to Lady Middleton for observing at this moment, “that it rained very hard,” though she believed the interruption to proceed less from any attention to her, than from her ladyship’s great dislike of all such inelegant subjects of raillery as delighted her husband and mother. The idea however started by her, was immediately pursued by Colonel Brandon, who was on every occasion mindful of the feelings of others; and much was said on the subject of rain by both of them. (Volume 1, Chapter 12)

Quotations are from the CUP editions of Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility, edited by Edward Copeland (2006), Mansfield Park, edited by John Wiltshire (2005), Pride and Prejudice, edited by Pat Rogers (2006), and Emma, edited by Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillan (2005).

Janet Todd is a retired academic; her last position was as President of Lucy Cavendish College, University of Cambridge. The photos above were taken in her garden.

If you enjoyed this post, I hope you’ll consider recommending it to a friend. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, please sign up to receive future posts, including the final guest post in “A Summer Party for Sense and Sensibility.” Tomorrow’s post, “A Calendar for Sense and Sensibility,” is by Ellen Moody.

Here are the links to the last two posts, in case you missed them:

On the Road with Elinor and Marianne, by Cheryl Bell

The Challenge of Interpreting Character and Action in Sense and Sensibility , by L. Bao Bui

Read more about my books, including Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues and Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, here.