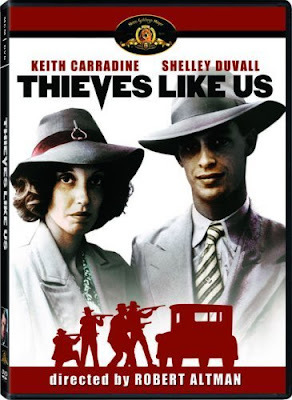

Capturing “Thieves Like Us”

In the wake of the criticaland popular success of 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, Hollywood was suddenlyhungry for other films that featured young lovers on the lam. I will not soonforget 1973’s Badlands, a fictionalized version of the real-life murderspree of two very young sweethearts. (That film marked the directorial debut ofTerrence Malick, and introduced many moviegoers to Sissy Spacek and MartinSheen.) In the following year, Robert Altman—best known at the time for M*A*S*H and The Long Goodbye—tried his hand at a period crime drama, ThievesLike Us. I sought it out as part of my personal farewell to the lateShelley Duvall, and found it both imaginatively conceived and surprisinglymoving.

Thieves Like Us is based on a 1937 novel that had previously beenadapted into a noir classic, They Live By Night, which marked thedirectorial debut of Nicholas Ray. While that 1948 film bowed slightlyto the moral requirements of its era, having its lovers marry and showing themale protagonist struggling with his conscience, Altman’s work is morematter-of-fact about the impulses that drive Bowie (well played by KeithCarradine) into an ongoing life of crime. Apparently, a tragic boyhood landedhim in prison at a very young age. Now he’s busted out, along with the erraticChickamaw (Altman favorite John Schuck), and they’ve teamed up with would-be-comedianT-Dub (Bert Remsen) to rob a series of local banks. This all takes place in ruralDepression-era Mississippi, and Bowie’s partners-in-crime seem to have a steadystream of local friends and relatives who’ll put them up (or put up with them)if need be.

Bowie seems happy enough togo along with the schemes of his more experienced pals. But an auto accidentputs him out of commission, and he finds himself being tended by Keechie, a shyyoung woman (Shelley Duval) who could badly use a little affection in her life.Needless to say, they quickly become lovers, and their destinies are foreverchanged. She wants a future based on happy domesticity; he’s not about to giveup the only source of income he knows. And he’s a bit proud, to be honest, thathis gang’s exploits are now making the local papers, complete with big photosand $100 bounties in store for those who bring then in, dead or alive. You can guess where all this leads.

Part of the film’s charm is Altman’scanny use of audio design. In place of a musical score, he relies on radiobroadcasts of the era to set the ongoing mood. Everyone’s life seems to revolvearound the radio, whether they’re at home or in their cars. In the course ofthe film, we hear snatches of crime dramas (Gangbusters! The Shadow!)as well as FDR’s Fireside Chats and Father Coughlin sermons. At one pointthere’s a snatch of something called The Royal Gelatin Hour. And thefilm’s big sex scene erupts while Keechie and the bed-ridden Bowie arelistening to a solemn Theater of the Air presentation of snippets fromShakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. This of course sets us up for the film’sinevitable tragic ending.

The other detail that helpscommunicate time and place is the fact that green glass bottles of Coca-Colaare present in almost every scene. But I’ll leave the final message toChickamaw, who—when all is said and done—wishes he’d paid attention in school andbecome a doctor, a lawyer, or a banker. If so, “I coulda robbed people with mybrain instead of a gun.”

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers