What Do They Need to Know?

The harder Tom tried to fasten his mind on his book, the more his ideas wandered. So at last, with a sigh and a yawn, he gave it up. It seemed to him that the noon recess would never come….Tom’s heart ached to be free, or else to have something of interest to do to pass the dreary time.

— The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain

How did the river make me a teacher? Listen. It was alive with paddle-wheel steamers in center channel, the turning paddles churning up clouds of white spray, making the green river boil bright orange where its chemical undercurrent was troubled; from shore you could clearly hear the loud thump thump thump on the water. From all over town young boys ran gazing in awe. A dozen times a day. No one ever became indifferent to these steamers because nothing important can ever really be boring.

— Dumbing us Down, by John Taylor Gatto

I’ve been watching old episodes of Alone on Netflix, and it’s gotten me thinking (because thinking is something I can do reasonably well, unlike skinning squirrels and insulating log cabins with moss).

Watching these contestants and learning about their lives back home—the survival classes they teach, the wilderness tours they lead, the hunting and fishing they did with their fathers—makes me think about people I’ve known in my own life who have had radically different upbringings from me—people who hunted for whatever meat they ate; people who valued the wilderness more than they did the city; people raised in poverty; people raised in the church. They are curious people and knowledgeable people. But they’re curious and knowledgeable about things I know little about. And it’s possible they’d say the same thing about me. But the things I know are the things our school systems and our various sets of learning standards tend to privilege and prioritize, while the things these other people know are barely ever whispered inside a schoolroom. Why?

Is it that we think of their knowledge as old-fashioned and outdated—not important in our increasingly urban and industrial world? If that’s the case, why do we ask children to study poetry from past centuries whose people had far more in common with our rural cousins than they have with us city-dwellers? So much of the poetic imagery we ask our students to analyze is based on the natural world, with references to particular flowers, birds, minerals, leaves, and sounds. But how much is tactile, experienced knowledge and understanding of the environment prioritized as essential in school?

The people who make decisions about schooling are, by and large, people who enjoyed school and were successful in it. I think this is part of the issue. They pass on to the next generation the things that worked for them. If they liked reading more than getting their hands dirty, then reading matters. If they were okay with sitting still for long periods of time, then sitting still is the right way to learn. This year’s star students resemble last year’s, and this year’s outliers resemble last year’s, ad infinitum.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This isn’t as hopeless and hermetically sealed as I’m making it seem. Diverse voices do creep into the curriculum (slowly), and pedagogical reforms do creep into the classroom (slowly). But what school is for, and what knowledge and skills matter—those things are tightly held, and if you widen your circle of empathy, you can understand why some people feel their lives and their culture are left out.

If the skills and knowledge that make up a set of learning standards are the most important things—the most enduring things—then they should matter to everyone to whom they are meant to apply. Which is why they tend to be written broadly, and why efforts at creating a national set of standards, which would have to be even broader, have failed in our very large and very diverse country.

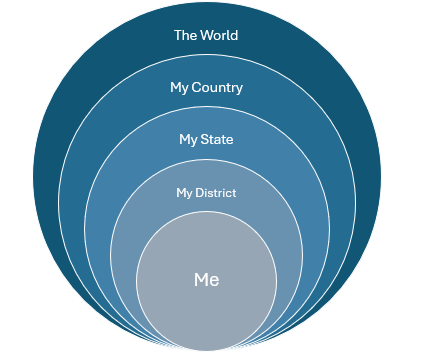

But that should be the floor, not the ceiling. Or, maybe more accurately, it should be the largest of a set of concentric circles. It is not the only circle that we should be dealing with.

When we design curriculum, we should be thinking of the largest world we’re trying to prepare our students to enter. And we have to think about the learning standards set for us by our state. But there should be room for variation and customization beyond that point. Even our smallest states are diverse. There are cities, suburbs, and rural areas. There are liberals and conservatives. There are deeply religious people and fiercely agnostic people. And even within those groups, there is subgroup variation and then, at the core, there are unique individuals. Each of those circles or rings is meaningful. And yet, we either ignore all of them except for the largest, or we agonize about “personalization” without thinking about anything that sits between the innermost circle and the outermost.

The twin goals of education should be to understand oneself and one’s world. But as you can see from the picture above, there are many worlds one has to learn about and live within—and their needs and values don’t always align nicely. Living in the world means understanding all of the variation within it and how to coexist respectfully and successfully with all of it.

The problem with buying, say, a U.S. History textbook from a national publisher is that the “state version” they create for your state will involve as short and limited a checklist of changes as they can get away with—for obvious reasons. It will include and exclude things as required, but it will still be a version of the national edition. It will be up to local teachers to help students get a deeper understand of the history and culture of their state and how that state sits within and sees the union of which it is a part.

But that’s just the start. They will also need to help students understand the town or city they live in and its relationship to both the state and the country. And they will need to help students understand the subgroups to which they belong and each group’s relationship to the larger population. And they will need to help students understand their weird, unique selves, and that self’s relationship to…everything.

It’s a tall order. No packaged, published curriculum can do all of that work for a teacher, and a traditional classroom and class period is a challenging structure in which to pull it off. But if we truly believe in providing equity as well as excellence—in respecting and valuing not only the “whole child,” but also the whole, diverse country—then we need to find ways to get there.

John Taylor Gatto, who launched the unschooling movement with his book, Dumbing us Down, says, “Nothing important can ever really be boring.” If we believe in the importance of what we’re teaching, but find some of our students to be bored, then something is getting in the way. Those kids are required by law to show up; they are not required to care. If we believe that our job is not only to help them know, but also to help them care, then we have work to do. And part of that work includes understanding better and caring more about the lives they live and the things they know before they ever walk into our buildings.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers