Voynich Reconsidered: scribes and languages

To my mind, the central mystery of the Voynich manuscript is whether there is a language underlying the strings of glyphs which have the appearance of text. That is the focus of my book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024). A corollary of that issue is whether there is more than one such language.

To my knowledge, the first proposition to this effect was made by Captain Prescott Currier, in Mary D’Imperio’s seminar in Washington, DC, in 1976. Currier told his audience:

Currier made it clear that he did not consider the difference between “languages” to be equivalent to the vernacular difference between, say, English and French. Nevertheless, his concept of two “languages” has passed into the canon of Voynich research. This concept encourages the researcher to imagine that part of the manuscript is derived from (say) Latin and another part from (say) Greek. I do not think that Currier intended that inference.

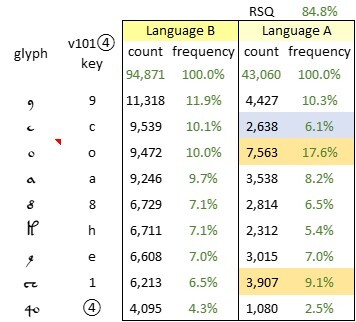

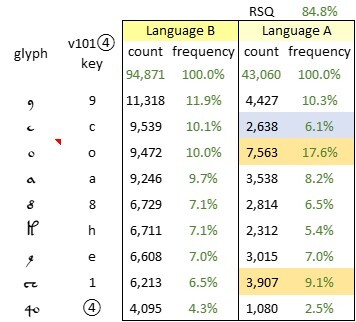

However, on the basis of Currier's assignment of pages to "languages", we can at least assess the overall statistical divergence between his "languages" A and B. I calculated the frequencies of the glyphs in his A and B pages, and juxtaposed the results. An extract, showing just the top ten glyphs in the B pages, is below.

The ten most frequent glyphs in the pages of the Voynich manuscript which Currier assigned to "language" B; and the frequencies of the same glyphs in "language" A. Counts and frequencies based on v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis.

Here I observed that across the whole glyph alphabet, the correlation between the glyph frequencies in the A pages and the B pages was 84.8 percent. The question then arose: was this correlation a sign of two different languages as we understand them today? Or did it simply represent two dissimilar source documents in a single language?

Corpora and texts

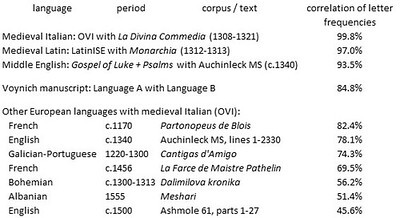

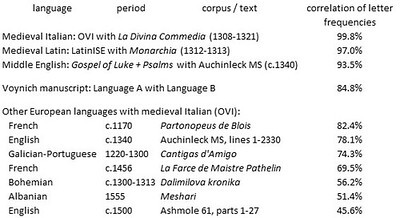

To elucidate this question, I selected two corpora and several texts in medieval European languages which used the Latin (or a mainly Latin) alphabet. The corpora contain thousands of texts; for example, the OVI corpus of medieval Italian, as of April 2024, included 3,512 texts with 30,443,280 words. For each corpus, I calculated the correlations between the letter frequencies in the corpus and those in selected texts, in the same language or another. An initial summary is below.

Correlations of the letter frequencies between two medieval European corpora and selected texts in the Latin (or mainly Latin) script. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1Ckwo

From these results, it seemed to me that documents in a common language were likely to have a correlation of letter frequencies in excess of 90 percent. On the other hand, documents in different languages were likely to have correlations in the range 50 to 80 percent.

The Voynich A-B correlation seemed to suggest that, if there were natural languages underlying the text, there could well be at least two.

Dr Davis and the five scribes

To the best of my knowledge, forty-four years passed before anyone reconsidered Currier’s concept of “languages”, and his related concept of “hands” or scribes. In 2020, Dr Lisa Fagin Davis, Executive Director of the Medieval Academy of America, presented her paper ”How Many Glyphs and How Many Scribes? Digital Paleography and the Voynich Manuscript”, which I think was the first elaboration and extension of Currier’s work.

As far as I can determine, Dr Davis did not substantively challenge Currier’s assignment of pages to “languages”; except that she preferred the term “dialect” rather than “language”. As I understood her paper, she accepted Currier's assignments of pages to A and B, with two exceptions; and the thirty pages which Currier had not assigned, she allocated to “dialect B”.

However, Dr Davis presented a significantly different view of the “hands” or scribes. Where Currier had identified seven scribes, she identified five. Her identifications included 67 pages which Currier had left unclassified, and differed from Currier’s in 32 other cases. Like Currier, she identified a principal scribe, whom I call “Scribe D1”, who was the single most prolific writer of the text; in her analysis, Scribe D1 wrote 113 of the 227 pages.

To my mind, Dr Davis’s view of the scribes is a springboard from which we can further reconstruct the statistical basis for Currier’s concept of “languages”.

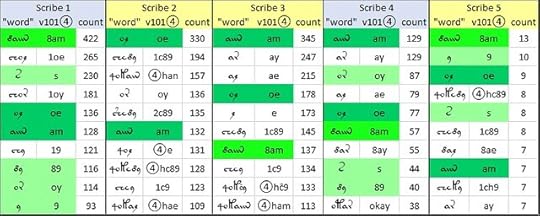

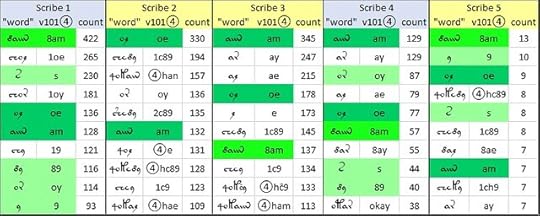

Starting from Dr Davis’s assignment of pages to scribes, I divided the text into five sections, each representing the work of a single scribe. I ran each section through the character frequency counter at browserling.com; this yielded a tabulation of glyph frequencies for each scribe. I then juxtaposed the five scribes’ glyph frequencies in a single Excel spreadsheet. An extract, showing just the top ten glyphs used by Scribe D1, is below.

The counts and frequencies of the top ten glyphs used by Scribe D1; and the counts and frequencies of the same glyphs as used by Scribes D2 through D5. Counts based on v101④ transliteration. RSQ1 denotes correlation with frequencies of Scribe D1. RSQ2 denotes correlation with frequencies of Scribe D2. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1oHrR

As shown in the table above, I calculated the correlation coefficients (as expressed by the RSQ function in Excel) between the glyph frequencies of the five scribes. To my mind, this yielded two results that might be significant in mapping from the Voynich text to natural languages, as follows:

The vocabularies of the scribes

Given that we have five distinct bodies of text, corresponding to Dr Davis’s five scribes, we can also start thinking about the vocabularies of the five sections. The extent to which the vocabularies differ may inform our view as to whether the sections represent languages or dialects, in the modern vernacular sense.

Running the five texts through the word counter at browserling.com produced complete listings of all the “words” used by each of the five scribes. I noted that differences between visually similar v101 glyphs such as (6}, {7}, {8} and {&} would create distinct “words”; therefore, it is entirely possible that the scribes’ vocabularies are overstated. With that reservation, their vocabularies were as follows:

Looking at the most frequent “words” used by each scribe, it became apparent that the five scribes had some commonalities in vocabulary, and also some divergences. For example, the “words” {am} and {oe} were among the top ten of all five scribes; the "word" {8am} was among the top ten of four scribes. But each scribe had between three and eight common vocabulary “words” that were less commonly used (but used nonetheless) by the others.

To my mind, these differences cannot represent different languages as we understand them today. But perhaps, as Dr Davis preferred to say, they represent different dialects of a common language with a substantial shared vocabulary.

The ten most frequent “words” used by each of the five scribes of the Voynich manuscript, as identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis. Counts based on v101④ transliteration. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1nwZD

I am aware of at least two modern instances (I imagine that there are more) in which a regional language or dialect is officially recognised as a national language. In the Scottish Parliament, any communication may be made in the Scots language, which is differentiated from English as in the following example:

And in Catalonia, the equivalent phrases in Catalan and Spanish are as follows:

More than this: perhaps scholars of linguistics could identify pairs of medieval languages or dialects that differ in letter frequencies and word frequencies in approximately the ways that we see among the five Voynich scribes. If so, that might greatly focus the search for the underlying languages of the manuscript.

To my knowledge, the first proposition to this effect was made by Captain Prescott Currier, in Mary D’Imperio’s seminar in Washington, DC, in 1976. Currier told his audience:

“The first twenty-five folios in the herbal section are obviously in one hand and one "language," which I called "A." … the text of this second portion of the herbal section (that is, the next twenty-five or thirty folios) is in two “languages” and each "language" is in its own hand.And that is all that we know about Currier’s “languages” A and B. Currier never defined the two “languages”, or specified the statistical mechanism or algorithm whereby he had distinguished A from B. He did however assign, for 197 of the 227 pages in the manuscript, the “language” of that page. He listed 114 pages in “language” A and 83 pages in “language” B. Implicitly, he was saying that each page contained only one “language”.

… my use of the word “language” is convenient, but it does not have the same connotations as it would have in normal use.

… the characteristics of "languages" A and B are obviously statistical. (I can't show you what they are here, as I don’t have slides prepared …) … There are two different series of agglomerations of symbols or letters, so that there are in fact two statistically distinguishable "languages”.”

Currier made it clear that he did not consider the difference between “languages” to be equivalent to the vernacular difference between, say, English and French. Nevertheless, his concept of two “languages” has passed into the canon of Voynich research. This concept encourages the researcher to imagine that part of the manuscript is derived from (say) Latin and another part from (say) Greek. I do not think that Currier intended that inference.

However, on the basis of Currier's assignment of pages to "languages", we can at least assess the overall statistical divergence between his "languages" A and B. I calculated the frequencies of the glyphs in his A and B pages, and juxtaposed the results. An extract, showing just the top ten glyphs in the B pages, is below.

The ten most frequent glyphs in the pages of the Voynich manuscript which Currier assigned to "language" B; and the frequencies of the same glyphs in "language" A. Counts and frequencies based on v101④ transliteration. Author's analysis.

Here I observed that across the whole glyph alphabet, the correlation between the glyph frequencies in the A pages and the B pages was 84.8 percent. The question then arose: was this correlation a sign of two different languages as we understand them today? Or did it simply represent two dissimilar source documents in a single language?

Corpora and texts

To elucidate this question, I selected two corpora and several texts in medieval European languages which used the Latin (or a mainly Latin) alphabet. The corpora contain thousands of texts; for example, the OVI corpus of medieval Italian, as of April 2024, included 3,512 texts with 30,443,280 words. For each corpus, I calculated the correlations between the letter frequencies in the corpus and those in selected texts, in the same language or another. An initial summary is below.

Correlations of the letter frequencies between two medieval European corpora and selected texts in the Latin (or mainly Latin) script. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1Ckwo

From these results, it seemed to me that documents in a common language were likely to have a correlation of letter frequencies in excess of 90 percent. On the other hand, documents in different languages were likely to have correlations in the range 50 to 80 percent.

The Voynich A-B correlation seemed to suggest that, if there were natural languages underlying the text, there could well be at least two.

Dr Davis and the five scribes

To the best of my knowledge, forty-four years passed before anyone reconsidered Currier’s concept of “languages”, and his related concept of “hands” or scribes. In 2020, Dr Lisa Fagin Davis, Executive Director of the Medieval Academy of America, presented her paper ”How Many Glyphs and How Many Scribes? Digital Paleography and the Voynich Manuscript”, which I think was the first elaboration and extension of Currier’s work.

As far as I can determine, Dr Davis did not substantively challenge Currier’s assignment of pages to “languages”; except that she preferred the term “dialect” rather than “language”. As I understood her paper, she accepted Currier's assignments of pages to A and B, with two exceptions; and the thirty pages which Currier had not assigned, she allocated to “dialect B”.

However, Dr Davis presented a significantly different view of the “hands” or scribes. Where Currier had identified seven scribes, she identified five. Her identifications included 67 pages which Currier had left unclassified, and differed from Currier’s in 32 other cases. Like Currier, she identified a principal scribe, whom I call “Scribe D1”, who was the single most prolific writer of the text; in her analysis, Scribe D1 wrote 113 of the 227 pages.

To my mind, Dr Davis’s view of the scribes is a springboard from which we can further reconstruct the statistical basis for Currier’s concept of “languages”.

Starting from Dr Davis’s assignment of pages to scribes, I divided the text into five sections, each representing the work of a single scribe. I ran each section through the character frequency counter at browserling.com; this yielded a tabulation of glyph frequencies for each scribe. I then juxtaposed the five scribes’ glyph frequencies in a single Excel spreadsheet. An extract, showing just the top ten glyphs used by Scribe D1, is below.

The counts and frequencies of the top ten glyphs used by Scribe D1; and the counts and frequencies of the same glyphs as used by Scribes D2 through D5. Counts based on v101④ transliteration. RSQ1 denotes correlation with frequencies of Scribe D1. RSQ2 denotes correlation with frequencies of Scribe D2. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1oHrR

As shown in the table above, I calculated the correlation coefficients (as expressed by the RSQ function in Excel) between the glyph frequencies of the five scribes. To my mind, this yielded two results that might be significant in mapping from the Voynich text to natural languages, as follows:

• Scribes D1 and D4 appeared to write in a common “language” or dialect.To my mind, these results seemed to underpin one of the processes that I have been using in all my attempted mappings from the Voynich text to natural languages: namely, to work with the text of a single scribe at a time. My preference has been to work with the text of Scribe D1 who, as I observed above, was the lead scribe.

• Scribes D2, D3 and D5 appeared to write in a common “language” or dialect, which was different from that of Scribes D1 and D4.

The vocabularies of the scribes

Given that we have five distinct bodies of text, corresponding to Dr Davis’s five scribes, we can also start thinking about the vocabularies of the five sections. The extent to which the vocabularies differ may inform our view as to whether the sections represent languages or dialects, in the modern vernacular sense.

Running the five texts through the word counter at browserling.com produced complete listings of all the “words” used by each of the five scribes. I noted that differences between visually similar v101 glyphs such as (6}, {7}, {8} and {&} would create distinct “words”; therefore, it is entirely possible that the scribes’ vocabularies are overstated. With that reservation, their vocabularies were as follows:

• Scribe 1: text 11,278 “words”, vocabulary, 3,655 “words”, hapax legomena 2,655 “words”The incidence of hapax legomena (“words” used only once) was in the range 19 to 24 percent for Scribes D1, D2 and D3. These percentages were comparable with those in medieval documents of similar length that I have examined. For example, in Der Ackerman aus Böhmen (Early Modern High German, c.1401), with 10,232 words, the incidence of hapax legomena is 20.6 percent.

• Scribe 2: text 9,813 “words”, vocabulary 2,686 “words”, hapax legomena 1,908 “words”

• Scribe 3: text 13,082 “words”, vocabulary 3,932 “words”, hapax legomena 2,767 “words”

• Scribe 4: text 5,576 “words”, vocabulary 2,652 “words”, hapax legomena 2,070 “words”

• Scribe 5: text 937 “words”, vocabulary 646 “words”, hapax legomena 527 “words”.

Looking at the most frequent “words” used by each scribe, it became apparent that the five scribes had some commonalities in vocabulary, and also some divergences. For example, the “words” {am} and {oe} were among the top ten of all five scribes; the "word" {8am} was among the top ten of four scribes. But each scribe had between three and eight common vocabulary “words” that were less commonly used (but used nonetheless) by the others.

To my mind, these differences cannot represent different languages as we understand them today. But perhaps, as Dr Davis preferred to say, they represent different dialects of a common language with a substantial shared vocabulary.

The ten most frequent “words” used by each of the five scribes of the Voynich manuscript, as identified by Dr Lisa Fagin Davis. Counts based on v101④ transliteration. Author’s analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2q1nwZD

I am aware of at least two modern instances (I imagine that there are more) in which a regional language or dialect is officially recognised as a national language. In the Scottish Parliament, any communication may be made in the Scots language, which is differentiated from English as in the following example:

• “The Scots language is an important part of Scotland's culture and heritage, appearing in songs, poetry and literature, as well as daily use in our communities.”Here, the words “leid”, “pairt”, “o”, “kythin”, “heirship”, “sang”, “poyems”, “leetratur”, “an”, “ilka”, “uiss”, “oor” and “forby” are Scots words which either do not exist, or do not have the same spelling or meaning, in English.

• “The Scots leid is a important pairt o Scotland's cultural heirship, kythin in sang, poyems an leetratur, an in ilka day uiss in oor communities forby.”

And in Catalonia, the equivalent phrases in Catalan and Spanish are as follows:

• “La llengua catalana és una part important de la cultura i el patrimoni de Catalunya, apareix en cançons, poesia i literatura, així com en l'ús quotidià a les nostres comunitats.”It seems to me possible that in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (and scholars of linguistics may correct me), regional languages or dialects had commonalities and divergences of the kind that we see in the writings of the five scribes of the Voynich manuscript.

• “La lengua catalana es una parte importante de la cultura y el patrimonio de Cataluña, apareciendo en canciones, poesía y literatura, así como en el uso diario en nuestras comunidades.”

More than this: perhaps scholars of linguistics could identify pairs of medieval languages or dialects that differ in letter frequencies and word frequencies in approximately the ways that we see among the five Voynich scribes. If so, that might greatly focus the search for the underlying languages of the manuscript.

Published on June 30, 2024 06:38

•

Tags:

currier, lisa-fagin-davis, schiffer, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers