Voynich Reconsidered: upper and lower case

In the search for meaning in the text of the Voynich manuscript, to my mind the researcher is well-advised to start with a strategy and a clearly defined set of assumptions. In the light of the results that emerge, those assumptions may change. As I have reported in previous articles on this platform, my working assumptions include the following:

I like to be guided by Occam’s Razor. Ockham is a village in Surrey, England. William of Ockham (later Occam) was a philosopher who lived from about 1287 to 1347. The principle to which he gave his name has been stated in many ways, among them the following: “It is futile to do with more, that which can be done with less”.

Since I expected simplicity in the Voynich producer’s instructions, and bearing Occam’s Razor in mind, I felt that an instruction of sufficient simplicity should map each distinct letter in the source documents uniquely to a distinct glyph in the Voynich manuscript. Reasonable persons may disagree; but to my mind, an instruction of this nature would enable the scribes to complete their work with minimal supervision.

The issue then arose: what alphabet could contain sufficient letters to yield mappings to at least 35 glyphs?

It seemed to me that such an alphabet must include all or most of the lower-case letters in the underlying script (whether Arabic, Cyrillic, Glagolitic, Greek, Latin or another). In addition, it must include either a number of accented letters (viewed as distinct from their unadorned counterparts); or a number of upper-case letters (if such existed in the alphabet); or both.

This consideration, to my mind, reduced the probability of precursor languages based on the Arabic alphabet, which has no cases. My corpora of medieval Arabic and Persian, for example, do not contain enough distinct letters to yield a mapping of the 35 most frequent Voynich glyphs, from {o} down to {M}. Ottoman Turkish has more variations on the Arabic alphabet, and remains a possibility, which I will investigate.

With regard to European languages: of the corpora and texts that I have investigated so far, all contain some proportion of upper case.

It seems to me that in works of prose, upper case is more frequent, either as a marker of the start of a sentence, or as the initial of a proper name. In German, upper case also denotes a noun, as in Der Ackermann aus Böhmen: “Ich bin genannt ein Ackermann” (“I was born a ploughman”). In poetry, upper case seems to be less common: for example in Dante’s La Divina Commedia, only the first letter of each three-line stanza is capitalised. As yet, we do not know whether the precursor documents of the Voynich manuscript were works of prose of poetry: although, as I wrote in Voynich Reconsidered, there is evidence of a poetic structure in the manuscript.

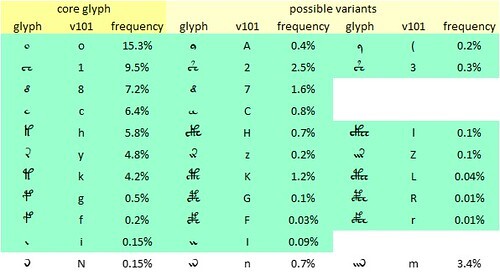

Counts of the more common letters in selected medieval languages, with and without case-sensitivity. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pYJJXj

These considerations led me to think about how the Voynich scribes might have dealt with upper and lower case. It seemed to be a simple assumption, of which Occam would have approved, that the scribes knew the languages of the source documents (and indeed, that they would have been hired on that criterion). Therefore, they would recognise the upper and lower cases of each letter.

I could think of several scenarios, including the following (and surely there are others):

In the second scenario, we could start by looking for visual resemblances between pairs of glyphs, in which one glyph (representing the lower case) is much more common than the other (representing the upper case).

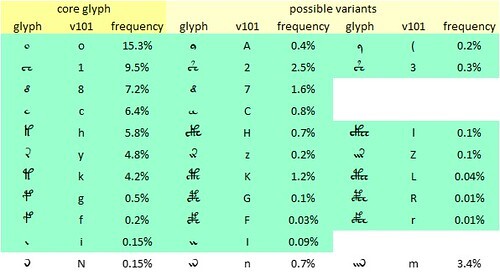

Selected "core glyphs", and possible variants with apparently embedded {i}, {E} or {c}. Author's analysis.

For example, I wondered whether the glyph {i} might be a marker of upper case. In the v101 transliteration, {i} on its own is not a common glyph; it has a frequency of 0.1 percent. However, we often see it apparently embedded in other glyphs. One example is {m} which could be read as {in}; but the frequencies are wrong, since {m} is much more common than {n}. Other examples, with the right frequency differentials, are {A} which could be {oi}; {7} which could be {8i}; and {I} which could be {ii}. We might conjecture that an {i} added to, or blended into, the right-hand side of the glyph is a marker of something; maybe of upper case.

Along the same lines, we might wonder whether what I call the “grand piano” glyphs are variants of their cousins the "gallows glyphs" and “bench glyphs”. For example {l} could be {Ehc} or {Hc}, and {L} could be {Ekc} or {Kc}. If so, the embedded {E} and {c} might be markers of something; again, maybe of upper case.

These are simply initial thoughts, which I think merit further investigation. More later.

• that there was a producer of the manuscript: possibly more than one, but there is no harm in imagining a single personI am inclined to see in these assumptions the following consequences:

• that the producer was sufficiently wealthy or (equivalently) powerful to engage a team of scribes and other artisans, and to pay for their work and supplies for a period of months or years

• that he or she provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages, and instructions whereby they were to create the sequences of symbols that we now call the Voynich glyphs.

• that the languages of the precursor documents are more likely to be European than not, and more likely to be medieval than modernIn previous articles on this platform, I examined three short sequences of glyphs on page f1r of the Voynich manuscript, which appear to be right-justified. I wanted to explore the hypothesis that these sequences might represent proper names. In the course of this work, I observed that one of these sequences contained the glyph that, in the v101 transliteration, is denoted by {M}. This glyph is not common: it is the 35th most frequent glyph in the Voynich manuscript.

• that the languages of the precursor documents are more likely to be alphabetic than not

• that the producer’s instructions to the scribes are more likely to be simple than complex.

I like to be guided by Occam’s Razor. Ockham is a village in Surrey, England. William of Ockham (later Occam) was a philosopher who lived from about 1287 to 1347. The principle to which he gave his name has been stated in many ways, among them the following: “It is futile to do with more, that which can be done with less”.

Since I expected simplicity in the Voynich producer’s instructions, and bearing Occam’s Razor in mind, I felt that an instruction of sufficient simplicity should map each distinct letter in the source documents uniquely to a distinct glyph in the Voynich manuscript. Reasonable persons may disagree; but to my mind, an instruction of this nature would enable the scribes to complete their work with minimal supervision.

The issue then arose: what alphabet could contain sufficient letters to yield mappings to at least 35 glyphs?

It seemed to me that such an alphabet must include all or most of the lower-case letters in the underlying script (whether Arabic, Cyrillic, Glagolitic, Greek, Latin or another). In addition, it must include either a number of accented letters (viewed as distinct from their unadorned counterparts); or a number of upper-case letters (if such existed in the alphabet); or both.

This consideration, to my mind, reduced the probability of precursor languages based on the Arabic alphabet, which has no cases. My corpora of medieval Arabic and Persian, for example, do not contain enough distinct letters to yield a mapping of the 35 most frequent Voynich glyphs, from {o} down to {M}. Ottoman Turkish has more variations on the Arabic alphabet, and remains a possibility, which I will investigate.

With regard to European languages: of the corpora and texts that I have investigated so far, all contain some proportion of upper case.

It seems to me that in works of prose, upper case is more frequent, either as a marker of the start of a sentence, or as the initial of a proper name. In German, upper case also denotes a noun, as in Der Ackermann aus Böhmen: “Ich bin genannt ein Ackermann” (“I was born a ploughman”). In poetry, upper case seems to be less common: for example in Dante’s La Divina Commedia, only the first letter of each three-line stanza is capitalised. As yet, we do not know whether the precursor documents of the Voynich manuscript were works of prose of poetry: although, as I wrote in Voynich Reconsidered, there is evidence of a poetic structure in the manuscript.

Counts of the more common letters in selected medieval languages, with and without case-sensitivity. Author's analysis. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pYJJXj

These considerations led me to think about how the Voynich scribes might have dealt with upper and lower case. It seemed to be a simple assumption, of which Occam would have approved, that the scribes knew the languages of the source documents (and indeed, that they would have been hired on that criterion). Therefore, they would recognise the upper and lower cases of each letter.

I could think of several scenarios, including the following (and surely there are others):

• The producer gave the scribes an explicit mapping of every upper-case and lower-case letter to a corresponding glyph, with no necessary visual resemblance between the two glyphs; as a completely hypothetical example, “e” could map to {o} and “E” could map to {8}.In the first scenario, we could use frequency analysis as a guide, as indeed I have in all of my attempts at mapping glyphs to letters. For example, in medieval Italian as represented by La Divina Commedia, the lower-case “e” has a frequency of 11.4 percent and has a good chance of mapping to the Voynich {o}; the upper-case “E” has a frequency of 0.2 percent and could plausibly map to any of the glyphs {z}, {f}, {u}, {*} or {(}.

• The producer gave the scribes more autonomy, in the form of a mapping of every lower-case letter to a corresponding glyph, and an algorithm for mapping the equivalent upper-case letter in some systematic way.

In the second scenario, we could start by looking for visual resemblances between pairs of glyphs, in which one glyph (representing the lower case) is much more common than the other (representing the upper case).

Selected "core glyphs", and possible variants with apparently embedded {i}, {E} or {c}. Author's analysis.

For example, I wondered whether the glyph {i} might be a marker of upper case. In the v101 transliteration, {i} on its own is not a common glyph; it has a frequency of 0.1 percent. However, we often see it apparently embedded in other glyphs. One example is {m} which could be read as {in}; but the frequencies are wrong, since {m} is much more common than {n}. Other examples, with the right frequency differentials, are {A} which could be {oi}; {7} which could be {8i}; and {I} which could be {ii}. We might conjecture that an {i} added to, or blended into, the right-hand side of the glyph is a marker of something; maybe of upper case.

Along the same lines, we might wonder whether what I call the “grand piano” glyphs are variants of their cousins the "gallows glyphs" and “bench glyphs”. For example {l} could be {Ehc} or {Hc}, and {L} could be {Ekc} or {Kc}. If so, the embedded {E} and {c} might be markers of something; again, maybe of upper case.

These are simply initial thoughts, which I think merit further investigation. More later.

Published on June 21, 2024 11:40

•

Tags:

voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers