Voynich Reconsidered: Adriano Cappelli and the Exon Domesday

In Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, 2024), I devoted a chapter to the idea of Latin as a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript, with a particular focus on abbreviated Latin as written in the fifteenth century. I drew upon Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon Abbreviaturarum (Ulrico Hoepli, 1929), which reproduces thousands of examples of the abbreviation symbols used in medieval documents in both Latin and Italian. I have continued to explore the hypothesis that the Voynich scribes worked with documents in abbreviated Latin.

The cover of Adriano Cappelli's "Lexicon Abbreviaturarum", third edition, published by Hoepli in 1929. Image credit: Ulrico Hoepli. Inset is a portrait of Cappelli (author unknown).

In my imagining of the Voynich workplace, I feel that if the Voynich producer had instructed the scribes to work from abbreviated Latin, he or she would have told them to transcribe the abbreviations as written: not to expand them. I do not imagine the scribes as authors or content creators; and I believe that the producer’s instructions had to be sufficiently simple that the scribes could complete the project with minimal supervision.

These assumptions (and they are no more than that) would help explain phenomena such as the Voynich glyph {9}, which is ubiquitous as the initial or final glyph of a Voynich “word”. As Cappelli demonstrated, a symbol resembling a 9 was used pervasively in medieval manuscripts to represent a wide range of prefixes and suffixes. In fact, in Lexicon Abbreviaturarum he included an eighteen-page section titled “Abbreviature comincianti coi segni 9 o Ↄ” (“Abbreviations beginning with the signs 9 or Ↄ”).

As with other languages that I have considered, the first step was to find a corpus of documents written in abbreviated Latin: preferably from the fifteenth century.

This task was tough.

Cappelli himself reproduced several facsimiles of documents in abbreviated Latin. In the accompanying text, he set out his interpretation of their meaning, but with the abbreviations expanded to conventional Latin. So it proved with most of the Latin documents and corpora that I found. The LatinISE medieval subcorpus, for example, is a wonderful resource for the analysis of conventional Latin; but all of the words are written in full.

After much searching, I found a document which retains the medieval abbreviations and, at least in principle, is amenable to machine-reading. The title is simply Exon Domesday; it is available online at https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/.

The term “Exon” is shorthand for “Exonia”, the Latin name for Exeter in England; and “Domesday” refers to the great survey of lands, buildings and livestock in England, ordered by King William in 1086. The website includes images of all the surviving pages of the original manuscript; transcriptions of the pages to expanded conventional Latin; and most importantly for my purposes, the transcription by Ralph Barnes, edited by Sir Henry Ellis and published in 1816, which retains the Latin abbreviations.

Extracts from the first folio, which bears page number 290, are reproduced below.

The first five lines of folio 1 of “Exon Domesday”. (top) in the original manuscript; (middle) as transcribed in the 1816 Ellis edition; (bottom) as expanded to conventional Latin. Image credits: "Exon: The Domesday Survey of South-West England", edited by P. A. Stokes, "Studies in Domesday", general editor J. Crick (London, 2018), available at http://www.exondomesday.ac.uk.

Here, the great obstacle that I encountered is that the Ellis edition, although it can be downloaded one page at a time, can be saved only as a series of png images. These images then have to be subjected to optical character recognition in order to yield machine-readable text. Each page of the Ellis edition contains about 2,000 characters including punctuation and abbreviation signs; for comparability with the approximately 150,000 glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, it would be necessary to download and apply OCR to about seventy-five pages. That already shapes up as a massive manual job.

The second obstacle is that the Ellis pages do not lend themselves to optical character recognition. Ralph Barnes used a special typeface (I think it was Record) to recreate the Latin abbreviation symbols. He included symbols approximating the modern Unicode characters đ, ł, ñ, and ⁹. OCR software, even when set to Latin as the language to be identified, does not deal well with such a diversity of symbols.

As a test, I downloaded the first thirteen lines of folio 1 of the Ellis edition, and applied my favorite OCR software. An extract from the results is below.

I persevered with a manual cleaning of the OCR text file, by reference to the Ellis edition and the manuscript, using Unicode symbols as approximations to the abbreviation signs. After much effort, the first thirteen lines bore a close resemblance to the Ellis edition. Again, an example is below.

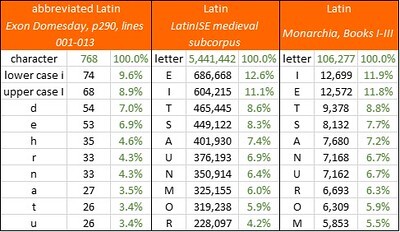

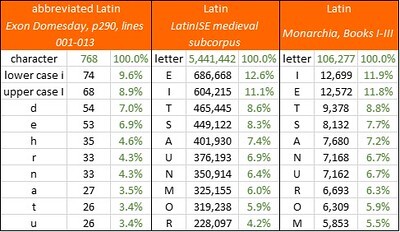

The top ten characters in “Exon Domesday”, p290, lines 1-13 (1086); the LatinISE medieval subcorpus, top 1,000 words, (7th-14th centuries); and Dante’s “Monarchia”, Books I-III (1312-13). Author’s analysis.

The sample is too small to take this analysis any further; but I note that the character frequencies in the sample from Exon Domesday are substantially different from those in LatinISE and Monarchia. Also, the Exon Domesday uses the lower-case i as a letter, and the upper-case I pervasively as the Roman numeral 1, which is atypical in relation to Latin narrative text.

Next steps

To entertain any hope of a robust statistical comparison between abbreviated Latin and the Voynich manuscript, we would need a machine-readable Latin text of at least 100,000 characters, which preserved the abbreviation symbols.

In terms of length, about fifty pages of the Ellis edition of Exon Domesday would serve the purpose. However, I am conscious that between the execution of Exon Domesday and the most recent carbon dates of samples from the Voynich manuscript, the best part of four centuries elapsed. I imagine that such an asynchronicity would render Exon Domesday an archaic document compared to anything that the Voynich scribes might have held in their hands.

May I invite readers to propose or direct me to documents in abbreviated Latin, of suitable length and with the abbreviation signs preserved, that might be more contemporary with the Voynich manuscript.

The cover of Adriano Cappelli's "Lexicon Abbreviaturarum", third edition, published by Hoepli in 1929. Image credit: Ulrico Hoepli. Inset is a portrait of Cappelli (author unknown).

In my imagining of the Voynich workplace, I feel that if the Voynich producer had instructed the scribes to work from abbreviated Latin, he or she would have told them to transcribe the abbreviations as written: not to expand them. I do not imagine the scribes as authors or content creators; and I believe that the producer’s instructions had to be sufficiently simple that the scribes could complete the project with minimal supervision.

These assumptions (and they are no more than that) would help explain phenomena such as the Voynich glyph {9}, which is ubiquitous as the initial or final glyph of a Voynich “word”. As Cappelli demonstrated, a symbol resembling a 9 was used pervasively in medieval manuscripts to represent a wide range of prefixes and suffixes. In fact, in Lexicon Abbreviaturarum he included an eighteen-page section titled “Abbreviature comincianti coi segni 9 o Ↄ” (“Abbreviations beginning with the signs 9 or Ↄ”).

As with other languages that I have considered, the first step was to find a corpus of documents written in abbreviated Latin: preferably from the fifteenth century.

This task was tough.

Cappelli himself reproduced several facsimiles of documents in abbreviated Latin. In the accompanying text, he set out his interpretation of their meaning, but with the abbreviations expanded to conventional Latin. So it proved with most of the Latin documents and corpora that I found. The LatinISE medieval subcorpus, for example, is a wonderful resource for the analysis of conventional Latin; but all of the words are written in full.

After much searching, I found a document which retains the medieval abbreviations and, at least in principle, is amenable to machine-reading. The title is simply Exon Domesday; it is available online at https://www.exondomesday.ac.uk/.

The term “Exon” is shorthand for “Exonia”, the Latin name for Exeter in England; and “Domesday” refers to the great survey of lands, buildings and livestock in England, ordered by King William in 1086. The website includes images of all the surviving pages of the original manuscript; transcriptions of the pages to expanded conventional Latin; and most importantly for my purposes, the transcription by Ralph Barnes, edited by Sir Henry Ellis and published in 1816, which retains the Latin abbreviations.

Extracts from the first folio, which bears page number 290, are reproduced below.

The first five lines of folio 1 of “Exon Domesday”. (top) in the original manuscript; (middle) as transcribed in the 1816 Ellis edition; (bottom) as expanded to conventional Latin. Image credits: "Exon: The Domesday Survey of South-West England", edited by P. A. Stokes, "Studies in Domesday", general editor J. Crick (London, 2018), available at http://www.exondomesday.ac.uk.

Here, the great obstacle that I encountered is that the Ellis edition, although it can be downloaded one page at a time, can be saved only as a series of png images. These images then have to be subjected to optical character recognition in order to yield machine-readable text. Each page of the Ellis edition contains about 2,000 characters including punctuation and abbreviation signs; for comparability with the approximately 150,000 glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, it would be necessary to download and apply OCR to about seventy-five pages. That already shapes up as a massive manual job.

The second obstacle is that the Ellis pages do not lend themselves to optical character recognition. Ralph Barnes used a special typeface (I think it was Record) to recreate the Latin abbreviation symbols. He included symbols approximating the modern Unicode characters đ, ł, ñ, and ⁹. OCR software, even when set to Latin as the language to be identified, does not deal well with such a diversity of symbols.

As a test, I downloaded the first thirteen lines of folio 1 of the Ellis edition, and applied my favorite OCR software. An extract from the results is below.

Iu HUND FERSTESFELT st. xr. hid& dimidia üg. De his hfit barones regis t dnio, stIt was apparent that my software had correctly identified most of the standard Latin letters but had failed to reproduce accurately the abbreviation symbols.

hid'&. r uirg. Inde ht hunfrid? de 1 fula, rt. hid. Ricard? eftormit. 1. hid. otre, r. hi, — Aldret

1. üg. À p. vir. bid dimid uirga min? habuit rex. xlr. fol. & 11. d. Illi etii q collegeft

geldü reddidert m denaf. 1. c; remanferat. ? 7 In hund dolesfelt st, Ixvzt. hid

& dim. 7 d.üg. Inde híit barones t dnio. xxxv. hid, & r üg & dfi, Eduuard? ui& vir.

I persevered with a manual cleaning of the OCR text file, by reference to the Ellis edition and the manuscript, using Unicode symbols as approximations to the abbreviation signs. After much effort, the first thirteen lines bore a close resemblance to the Ellis edition. Again, an example is below.

IN HUND⁴ FERSTESFELT sť XI · hid⁴ & dimidia ũg̃ · De his hñt barones regis ĩ dnĩo · IIII ·At this juncture, I had produced a small machine-readable sample of abbreviated Latin text, with 885 characters, of which 768 were Latin letters or abbreviation signs. The sample was entirely too small to be comparable with the Voynich manuscript; but I thought that it justified an experiment in frequency analysis. Running the sample through the Browserling character counter yielded a letter frequency distribution, in which for the time being, I combined upper and lower case letters. This distribution could then be compared with the letter frequencies in the LatinISE medieval subcorpus, and in Dante’s Monarchia. An extract from the results is below.

hid⁴ & · I uirg̃ · Inde hť hunfrid⁹ de ĩſula · II · hid⁴ · Ricard⁹ eſtormit · I · hiđ · otre · I · hid · Aldret

I · ũg̃ · & p · VII · hiđ dimiđ uirga min⁹ habuit rex · XlI · foł · & II · đ · Illi etiā q collegeřt

geldũ reddideřt mᵒ denař · I · q¹ remanſerat · ⑦ In hund dolesfelt sť IXVII hiđ

& dim⁴ · 7 đ · ũg̃ · Inde hñt barones ĩ dnĩo · XXXV · hiđ · & · I · ũg̃ & dḿ · Eduuard⁹ uić · VII ·

The top ten characters in “Exon Domesday”, p290, lines 1-13 (1086); the LatinISE medieval subcorpus, top 1,000 words, (7th-14th centuries); and Dante’s “Monarchia”, Books I-III (1312-13). Author’s analysis.

The sample is too small to take this analysis any further; but I note that the character frequencies in the sample from Exon Domesday are substantially different from those in LatinISE and Monarchia. Also, the Exon Domesday uses the lower-case i as a letter, and the upper-case I pervasively as the Roman numeral 1, which is atypical in relation to Latin narrative text.

Next steps

To entertain any hope of a robust statistical comparison between abbreviated Latin and the Voynich manuscript, we would need a machine-readable Latin text of at least 100,000 characters, which preserved the abbreviation symbols.

In terms of length, about fifty pages of the Ellis edition of Exon Domesday would serve the purpose. However, I am conscious that between the execution of Exon Domesday and the most recent carbon dates of samples from the Voynich manuscript, the best part of four centuries elapsed. I imagine that such an asynchronicity would render Exon Domesday an archaic document compared to anything that the Voynich scribes might have held in their hands.

May I invite readers to propose or direct me to documents in abbreviated Latin, of suitable length and with the abbreviation signs preserved, that might be more contemporary with the Voynich manuscript.

Published on May 09, 2024 06:15

•

Tags:

adriano-cappelli, exon-domesday, henry-ellis, ralph-barnes, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers