Voynich Reconsidered: Bohemian as precursor

Wilfrid Voynich was said to have bought the Voynich manuscript in central Italy. In my ongoing search for the underlying languages of the manuscript, and with a view to radiating the search outwards from Italy, I considered the languages of neighboring countries. One such language is Old Bohemian (the precursor of the modern Czech language).

The first step was to find documents in Old Bohemian, from which I could calculate the letter frequencies.

One interesting candidate document was Dalimilova kronika (The Chronicle of Dalimil), which is said to be the earliest manuscript in Bohemian. The manuscript is richly illustrated; the text is in verse; the author is unknown. In its original version, it relates events in the land of Croatia (which then encompassed what is now Czechia) up to the year 1314. It is therefore assumed to have been composed early in the fourteenth century.

My first problem was that every electronic full text that I could find was written in what appeared to be the modern Czech language. For example, in one popular version the first three lines are as follows:

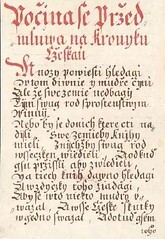

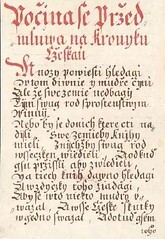

The first page of text of the original Dalimilova kronika. Image by courtesy of Petar B. Bogunovic.

As I read it, the modern “ě” was written “ie”, “v” was written “w”, “j” was written “g”, and many modern accents were absent. The letter frequencies would therefore be substantially different in Bohemian from those in modern Czech.

In the absence of an electronic full text in Bohemian, I created my own version of Dalimilova kronika, starting with the modern version and making as many substitutions as I could identify from the first page of the original. This reduced the alphabet from forty letters in Czech to twenty-five in Bohemian. After converting all letters to lower case and removing punctuation, I had a flat text file with 25,460 words and 131,200 characters excluding spaces.

As I have reported in previous posts on this platform, I have been using four tests for the hypothesis that a given language could be an underlying language of the Voynich manuscript:

In my rendition of Dalimilova kronika, the average word length was 5.15 letters, which was substantially longer than the average of 3.78 glyphs in my v101④ transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. So there was already some discouragement of the idea that the Voynich scribes had worked from documents in Old Bohemian.

Alternative transliterations

Among my thirty-seven alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, those that had the best statistical fit with Dalimilova kronika were as follows:

Letter and glyph frequencies

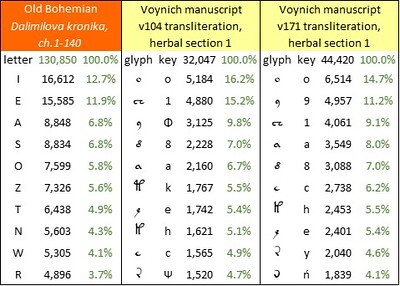

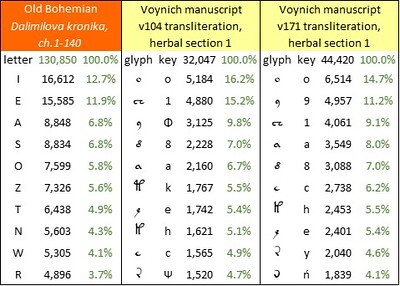

The most frequent letters in Dalimilova kronika, and the most frequent glyphs in the v104 and v171 transliterations, were as follows:

The ten most frequent letters in the Old Bohemian language, represented by "Dalimilova kronika"; and the ten most frequent glyphs in my v104 and v171 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

Test mappings

The crucial test was to attempt mappings to Old Bohemian from selected extracts from the Voynich text, for which purpose I again used the most frequent “words” of one to four glyphs in the v104 and v171 transliterations.

Here, the v104 transliteration yielded no Old Bohemian words longer than one letter; the v171 transliteration yielded no words longer than two letters.

In summary, my comparisons of word length and frequencies, and my test mappings of glyphs to letters, have not supported the hypothesis that Old Bohemian was an underlying language of the Voynich manuscript.

As with the other languages that we have investigated: it remains to be considered that, as Mary D’Imperio’s “five states” and Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet" suggest, the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in every "word". We can imagine that the producer gave them a prescribed sequence that the glyphs had to follow. If that is so, our mappings might not be the last step. Each of the mapped strings might have a predecessor, with the same letters but in a different order - in effect, an anagram. However, I have tested all of the text strings in this way, without finding any common Bohemian word.

The first step was to find documents in Old Bohemian, from which I could calculate the letter frequencies.

One interesting candidate document was Dalimilova kronika (The Chronicle of Dalimil), which is said to be the earliest manuscript in Bohemian. The manuscript is richly illustrated; the text is in verse; the author is unknown. In its original version, it relates events in the land of Croatia (which then encompassed what is now Czechia) up to the year 1314. It is therefore assumed to have been composed early in the fourteenth century.

My first problem was that every electronic full text that I could find was written in what appeared to be the modern Czech language. For example, in one popular version the first three lines are as follows:

Mnozí pověstí hledajú,However, the Old Bohemian language was substantially different from modern Czech. Notably, Old Bohemian had fewer accents. My reading of the first three lines in the original is approximately as follows:

v tom múdřě i dvorně činie,

ale ţe své země netbajú …

Mnozy powiesti hledagi

wtom diwnie y mudře čyni

ale že sivezemie nedbagy …

The first page of text of the original Dalimilova kronika. Image by courtesy of Petar B. Bogunovic.

As I read it, the modern “ě” was written “ie”, “v” was written “w”, “j” was written “g”, and many modern accents were absent. The letter frequencies would therefore be substantially different in Bohemian from those in modern Czech.

In the absence of an electronic full text in Bohemian, I created my own version of Dalimilova kronika, starting with the modern version and making as many substitutions as I could identify from the first page of the original. This reduced the alphabet from forty letters in Czech to twenty-five in Bohemian. After converting all letters to lower case and removing punctuation, I had a flat text file with 25,460 words and 131,200 characters excluding spaces.

As I have reported in previous posts on this platform, I have been using four tests for the hypothesis that a given language could be an underlying language of the Voynich manuscript:

• The average length of words should be similar to that of the Voynich "words": that is, about 4.0 letters or less.Word lengths

• There should be a good correlation between the frequencies of the letters and the frequencies of the Voynich glyphs: preferably, at least 95 per cent.

• There should be a low average absolute difference between the frequencies of the letters and the frequencies of the equally-ranked Voynich glyphs: preferably, at most 0.4 per cent.

• A test mapping of Voynich glyph strings to letters (in the candidate language) should produce at least some intelligible words: preferably words of at least four letters.

In my rendition of Dalimilova kronika, the average word length was 5.15 letters, which was substantially longer than the average of 3.78 glyphs in my v101④ transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. So there was already some discouragement of the idea that the Voynich scribes had worked from documents in Old Bohemian.

Alternative transliterations

Among my thirty-seven alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, those that had the best statistical fit with Dalimilova kronika were as follows:

v104, which differs from v101④ in the following respects:However, the statistical fits are not brilliant. The v104 transliteration has the best correlation of glyph frequencies with Old Bohemian letter frequencies, but it is only 93.0 percent. The v171 transliteration has the best absolute frequency difference, but it is 0.92 percent which is high by comparison with my results for other medieval European languages. At this stage it already seems that the Old Bohemian language has a substantially different “shape” (as represented by the letter frequencies) from the “shape” of the Voynich manuscript.

• The glyphs {2}, {3}, {5}, {!}, {%}, {+} and {#} are all equated with {1} plus a catch-all accent {‘};

• The glyphs {6}, {7}, and {&} are all equated with {8}

• The “bench gallows” glyphs are redefined as “gallows” + “bench”, and the “bench” is assumed to be the glyph {1}: so {F} = {f1} and so on;

• The “double glyph” {I} is disaggregated: {I} = {ii};

• The glyphs {m}, {M} and {n} are disaggregated into strings, so that {m} = {iiΩ}, {M} = {iiiΩ}, {n} = {iΩ};

• A few less common glyphs are equated with more common ones: {( }= {Φ}; {A} = {o}; {*}, {Q} = {Π}; {P} = {iΠ}.

v171, which has the following variations from v101④:

• The glyphs {m}, {M} and {n} are disaggregated into strings, so that {m} => {îń}, {M} => {iîń}, {n} => {iń}.

Letter and glyph frequencies

The most frequent letters in Dalimilova kronika, and the most frequent glyphs in the v104 and v171 transliterations, were as follows:

The ten most frequent letters in the Old Bohemian language, represented by "Dalimilova kronika"; and the ten most frequent glyphs in my v104 and v171 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

Test mappings

The crucial test was to attempt mappings to Old Bohemian from selected extracts from the Voynich text, for which purpose I again used the most frequent “words” of one to four glyphs in the v104 and v171 transliterations.

Here, the v104 transliteration yielded no Old Bohemian words longer than one letter; the v171 transliteration yielded no words longer than two letters.

In summary, my comparisons of word length and frequencies, and my test mappings of glyphs to letters, have not supported the hypothesis that Old Bohemian was an underlying language of the Voynich manuscript.

As with the other languages that we have investigated: it remains to be considered that, as Mary D’Imperio’s “five states” and Massimiliano Zattera's "slot alphabet" suggest, the Voynich scribes re-ordered the glyphs in every "word". We can imagine that the producer gave them a prescribed sequence that the glyphs had to follow. If that is so, our mappings might not be the last step. Each of the mapped strings might have a predecessor, with the same letters but in a different order - in effect, an anagram. However, I have tested all of the text strings in this way, without finding any common Bohemian word.

Published on May 05, 2024 04:19

•

Tags:

bohemian, dalimil, dalimila-kronika, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers