Voynich Reconsidered: Welsh as precursor

In my research for Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024), I prioritised the languages spoken in or near medieval Italy as potential precursors of the Voynich text. The languages of northern Europe seemed geographically rather remote. However, I thought it prudent to widen the net. In so doing, I investigated the Middle Welsh language.

I am using the term "Middle Welsh" to refer to the Welsh language as spoken and written from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.

As with other languages that I have examined, the first step in this process was to identify a suitable corpus of documents of the right time period. For this purpose, I thought of the Peniarth Manuscripts.

At the National Library of Wales, the Peniarth Manuscripts are the single most important collection. These manuscripts were collected by Robert Vaughan (c.1592-1667), whose library was in Hengwrt, Meirioneth county. Among the collection there are several manuscripts in Middle Welsh from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, including the following:

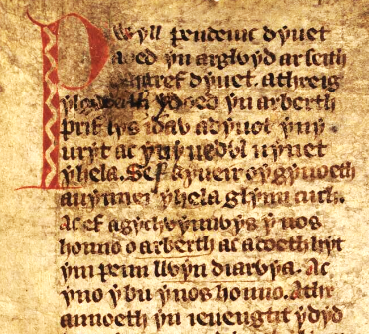

The first thirteen lines of the first page of Peniarth MS4. The first sentence is "Pwẏll pendeuic dẏuet a|oed ẏn arglỽẏd ar seith cantref dẏuet" (Pwyll Prince of Dyfed was lord over the seven cantrefs of Dyfed"). Image credit: National Library of Wales.

Word length

My copy of The White Book of Mabinogion contains 112,154 words, with 430,466 letters (excluding punctuation), for an average word length of 3.84 letters. To make a comparison with the Voynich manuscript, I selected my v101④ transliteration. This differs from Glen Claston’s v101 in that I replace all instances of the v101 string {4o} with the Unicode symbol ④. In v101④, the average length of a “word” is 3.78 glyphs.

Glyph and letter frequencies

As I have outlined in other articles on this platform, I have worked on the assumption that there is no single “best” transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. There are several symbols, like the v101 {m}, that might be a single glyph or a ligature of several glyphs. There are several families of glyphs, such as the v101 {6}, {7}, {8} and {&}, that could be distinct glyphs, or could be no more than variations in handwriting. Therefore, I have taken the position that we need multiple transliterations; and selecting one over another is a matter of trial and error.

Accordingly, as of this writing, I have developed thirty-seven alternative transliterations, each derived from Claston’s v101 but differing from v101 in one respect or several respects. When investigating a possible mapping to a target precursor language, I have used two alternative metrics: the statistical correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies, and the average absolute difference between the frequencies of equally-ranked glyphs and letters.

Of these transliterations, two have a good statistical fit with The White Book of Mabinogion, as follows:

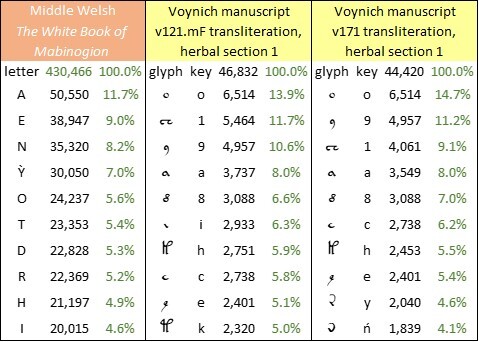

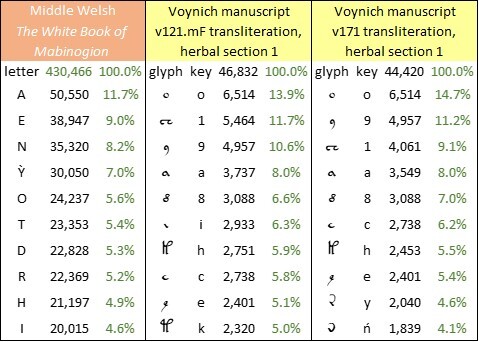

The most frequent glyphs in the v121.mF and v171 transliterations, and the most frequent letters in The White Book of Mabinogion, are as follows:

The ten most frequent letters in Middle Welsh, as represented by "The White Book of Mabinogion", and the ten most frequent glyphs in my v121.mF and v171 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

Mapping the Voynich

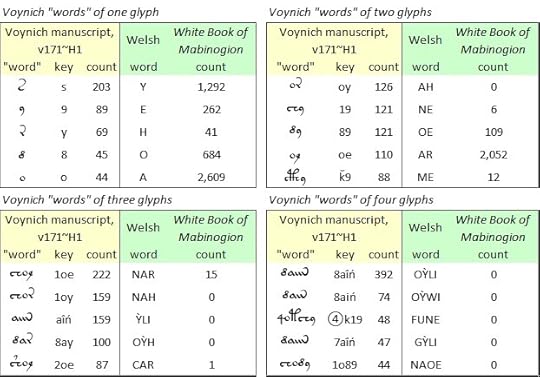

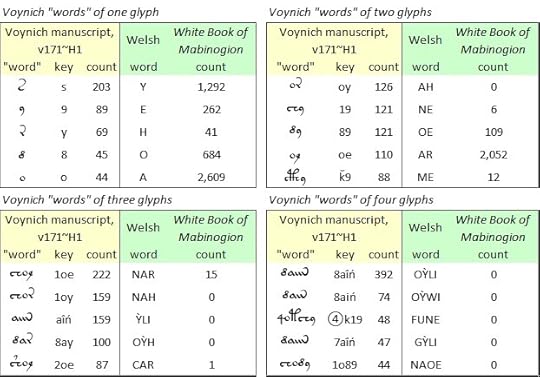

With that, I again embarked on my standard test of mapping the most frequent Voynich “words” of one to four glyphs to text strings in the target language. I tested the v121.mF and v171 transliterations separately. In each case, for some assurance of mapping from a uniform language, I used the "herbal" section. I searched for each text string in The White Book of Mabinogion to see whether it occurred as a real word, and if so, how often.

The v121.mF transliteration yielded essentially no real words in Middle Welsh, except for some single-letter words which could be the product of chance. The v171 transliteration yielded real Welsh words of one and two letters; the most encouraging was the “word” {oe} yielding the Welsh “ar” (in English, “on”). But, as I had found with several other target languages, at the three-glyph and four-glyph level the mapping broke down.

Provisional mappings of the most common "words" of one to four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v171 transliteration, to Middle Welsh. Author's analysis.

My provisional conclusion is that Middle Welsh, at least as represented by The White Book of Mabinogion, is probably not a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript.

I am using the term "Middle Welsh" to refer to the Welsh language as spoken and written from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.

As with other languages that I have examined, the first step in this process was to identify a suitable corpus of documents of the right time period. For this purpose, I thought of the Peniarth Manuscripts.

At the National Library of Wales, the Peniarth Manuscripts are the single most important collection. These manuscripts were collected by Robert Vaughan (c.1592-1667), whose library was in Hengwrt, Meirioneth county. Among the collection there are several manuscripts in Middle Welsh from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, including the following:

• Peniarth MS 4: Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch (The White Book of Rhydderch), copied in the mid-fourteenth century, which contains the earliest copy of the Middle Welsh tales now collectively known as the MabinogionAccordingly, I downloaded The White Book of Mabinogion: Welsh tales [and] romances produced from the Peniarth manuscripts, which is a compilation by John Gwenogvryn Evans of tales from Peniarth Manuscripts 4 and 6. I believe that this compilation reproduces accurately the text in the original manuscripts.

• Peniarth MS 6: which contains fragments of Branwen, Manawydan and Geraint ap Erbin, from the second half of the thirteenth century.

The first thirteen lines of the first page of Peniarth MS4. The first sentence is "Pwẏll pendeuic dẏuet a|oed ẏn arglỽẏd ar seith cantref dẏuet" (Pwyll Prince of Dyfed was lord over the seven cantrefs of Dyfed"). Image credit: National Library of Wales.

Word length

My copy of The White Book of Mabinogion contains 112,154 words, with 430,466 letters (excluding punctuation), for an average word length of 3.84 letters. To make a comparison with the Voynich manuscript, I selected my v101④ transliteration. This differs from Glen Claston’s v101 in that I replace all instances of the v101 string {4o} with the Unicode symbol ④. In v101④, the average length of a “word” is 3.78 glyphs.

Glyph and letter frequencies

As I have outlined in other articles on this platform, I have worked on the assumption that there is no single “best” transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. There are several symbols, like the v101 {m}, that might be a single glyph or a ligature of several glyphs. There are several families of glyphs, such as the v101 {6}, {7}, {8} and {&}, that could be distinct glyphs, or could be no more than variations in handwriting. Therefore, I have taken the position that we need multiple transliterations; and selecting one over another is a matter of trial and error.

Accordingly, as of this writing, I have developed thirty-seven alternative transliterations, each derived from Claston’s v101 but differing from v101 in one respect or several respects. When investigating a possible mapping to a target precursor language, I have used two alternative metrics: the statistical correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies, and the average absolute difference between the frequencies of equally-ranked glyphs and letters.

Of these transliterations, two have a good statistical fit with The White Book of Mabinogion, as follows:

• v121.mF, which has the following variations from v101④:These statistical fits are comparable with the best results that I have previously found: those of my comparisons between the Voynich manuscript and documents in medieval Latin and Italian.o The v101 glyphs {2}, {3}, {5}, {!}, {%}, {+} and {#} are all equated with v101 {1} plus a catch-all accent {‘};• The glyph frequencies in v121.mF have the highest correlation (97.2 percent) with the letter frequencies in The White Book of Mabinogion.

o The v101 glyph {m} is disaggregated into the three-glyph string {iiń};

o The “bench gallows” glyphs are redefined as gallows + bench, so that {F} becomes {fπ} and so on;

o The v101 glyph {A} is equated with {a}

• v171, which has the following variations from v101④:o The v101 glyphs {m}, {M} and {n} are disaggregated, so that {m} => {îń}, {M} => {iîń}, {n} => {iń}• The glyph frequencies in v171 have the lowest average absolute difference (0.38 percent) from the frequencies of equally-ranked letters in The White Book of Mabinogion.

The most frequent glyphs in the v121.mF and v171 transliterations, and the most frequent letters in The White Book of Mabinogion, are as follows:

The ten most frequent letters in Middle Welsh, as represented by "The White Book of Mabinogion", and the ten most frequent glyphs in my v121.mF and v171 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

Mapping the Voynich

With that, I again embarked on my standard test of mapping the most frequent Voynich “words” of one to four glyphs to text strings in the target language. I tested the v121.mF and v171 transliterations separately. In each case, for some assurance of mapping from a uniform language, I used the "herbal" section. I searched for each text string in The White Book of Mabinogion to see whether it occurred as a real word, and if so, how often.

The v121.mF transliteration yielded essentially no real words in Middle Welsh, except for some single-letter words which could be the product of chance. The v171 transliteration yielded real Welsh words of one and two letters; the most encouraging was the “word” {oe} yielding the Welsh “ar” (in English, “on”). But, as I had found with several other target languages, at the three-glyph and four-glyph level the mapping broke down.

Provisional mappings of the most common "words" of one to four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v171 transliteration, to Middle Welsh. Author's analysis.

My provisional conclusion is that Middle Welsh, at least as represented by The White Book of Mabinogion, is probably not a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript.

Published on May 04, 2024 11:35

•

Tags:

mabinogion, middle-welsh, peniarth, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers